Below are the three stars of our waistcoat collection, illustrating the progression of aesthetic and production styles across the course of a century.

From an extremely fine, elaborately embroidered and inlaid example of the late 18th century from the Wilberforce family, to a cheery floral item of the early 19th and a 'Perkins Mauve' silk piece from the later 19th century.

From an extremely fine, elaborately embroidered and inlaid example of the late 18th century from the Wilberforce family, to a cheery floral item of the early 19th and a 'Perkins Mauve' silk piece from the later 19th century.

#1 - The Wilberforce Waistcoat, c. 1770-90

|

Undoubtedly one of the finest items in the collection, this elaborately decorated silk waistcoat dates from the zenith of an extravagant era in male fashion.

From the Wilberforce family, it may have once belonged to the famed abolitionist William Wilberforce. With embroidered floral patterns in coloured and silver thread and inlaid blue and white glass petals, the number of hours put into creating this stunning piece of clothing by extremely skilled craftspeople can only be imagined - along with the undoubtedly vast cost for such work. |

The detailed embroidery extends to each individual button, while on a more practical note, the centre seam at the rear has been opened, with cotton bands added to extend the size.

'Worn by Bishop Wilberforce' - the single piece of highly intriguing provenance that came with the piece, which was originally donated by Lady Burrell of the Knepp estate in the 1970s.

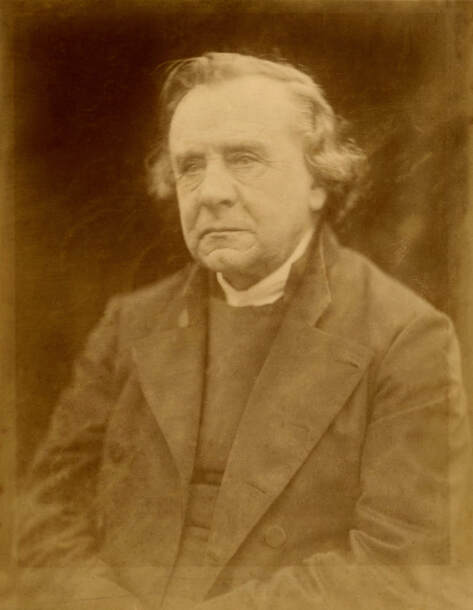

There were two Bishop Wilberforces, father and son. Samuel (1805-1873) was Bishop of Oxford and of Winchester. Known for his oratory and church reform in his own time, he is famed today for his dramatic high stakes public debate with T.H. Huxley on the subject of Darwin's recently published Origin of Species. His son Ernest (1840-1908) was Bishop of Newcastle upon Tyne and then Chichester. However, the date of the waistcoat tempts the additional exciting question - was it originally made for Samuel's father, the famed anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce?

A decadent item in its own day, by the time of Samuel's youth, such a style was a long out of fashion throwback to an 18th century excess subsumed in the revolution and war of the last decade of that century. Quite why the up and coming churchman Samuel would have acquired and then worn such a relic is unclear - Ernest even less so. William was certainly gregarious in his youth and cut very much a different figure to the serious man he later became. Attending society gatherings, dances and gambling clubs regularly, he was also at the top of the social set. Having become an MP at the age of 21, he was a close friend of the energetic soon to be Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger.

In fact, William took a six week trip to France in the autumn of 1783 and Grand Tour of the French Riviera, Italy and Switzerland in the winter of 1784-5. Could a French or Italian tailor have created this waistcoat as a souvenir? The uninhibited stylings would certainly have been at home in the social milieu of Florence or pre Revolutionary Paris. These trips were taken just prior to the strengthening of William's evangelical religious convictions and subsequent inner turmoil about his lifestyle. His companion Isaac Milner aided this on the latter trip and after this point it is easy to imagine that he would eventually have been embarrassed to have been seen wearing anything like this, showpiece or otherwise.

William's personal shift is very clear in Charles Shore's much later 1820 description, well into the Regency dress revolution: '[He] invariably wore black clothes, sometimes till they became quite dingy, for he ignored his outer man, never, as his valet intimated...making use of a glass... He was quite unconscious of the notice which his personal appearance attracted...

Few men have been so little influenced by the distracting passions of ambition, avarice, vanity, and resentment...' If ever evidence were needed that the nature of man can change!

So, acquired second hand for an unknown reason by Bishop Samuel or Ernest Wilberforce? Or was this waistcoat once a prized possession of William Wilberforce's unreformed youth, and later memento of his prior life handed down in the family? Unless further evidence comes to light, the latter can remain only a tempting speculation.

There were two Bishop Wilberforces, father and son. Samuel (1805-1873) was Bishop of Oxford and of Winchester. Known for his oratory and church reform in his own time, he is famed today for his dramatic high stakes public debate with T.H. Huxley on the subject of Darwin's recently published Origin of Species. His son Ernest (1840-1908) was Bishop of Newcastle upon Tyne and then Chichester. However, the date of the waistcoat tempts the additional exciting question - was it originally made for Samuel's father, the famed anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce?

A decadent item in its own day, by the time of Samuel's youth, such a style was a long out of fashion throwback to an 18th century excess subsumed in the revolution and war of the last decade of that century. Quite why the up and coming churchman Samuel would have acquired and then worn such a relic is unclear - Ernest even less so. William was certainly gregarious in his youth and cut very much a different figure to the serious man he later became. Attending society gatherings, dances and gambling clubs regularly, he was also at the top of the social set. Having become an MP at the age of 21, he was a close friend of the energetic soon to be Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger.

In fact, William took a six week trip to France in the autumn of 1783 and Grand Tour of the French Riviera, Italy and Switzerland in the winter of 1784-5. Could a French or Italian tailor have created this waistcoat as a souvenir? The uninhibited stylings would certainly have been at home in the social milieu of Florence or pre Revolutionary Paris. These trips were taken just prior to the strengthening of William's evangelical religious convictions and subsequent inner turmoil about his lifestyle. His companion Isaac Milner aided this on the latter trip and after this point it is easy to imagine that he would eventually have been embarrassed to have been seen wearing anything like this, showpiece or otherwise.

William's personal shift is very clear in Charles Shore's much later 1820 description, well into the Regency dress revolution: '[He] invariably wore black clothes, sometimes till they became quite dingy, for he ignored his outer man, never, as his valet intimated...making use of a glass... He was quite unconscious of the notice which his personal appearance attracted...

Few men have been so little influenced by the distracting passions of ambition, avarice, vanity, and resentment...' If ever evidence were needed that the nature of man can change!

So, acquired second hand for an unknown reason by Bishop Samuel or Ernest Wilberforce? Or was this waistcoat once a prized possession of William Wilberforce's unreformed youth, and later memento of his prior life handed down in the family? Unless further evidence comes to light, the latter can remain only a tempting speculation.

#2 - The Floral Waistcoat, c. 1830s - 1840s

|

This twill waistcoat brings to mind a spirit of festive cheer, emblematic of a time in fashion when men of the day from Dickens to Darwin could be seen sporting similarly elaborately patterned designs.

It sports a sprigged floral pattern reminiscent of holly, with a roll design to the pockets and shawl collar. While its aesthetic might today suggest being brought out on special occasions, it is very much well worn, has multiple stains and features a number of hand sewn repairs. This suggests much use over the years, perhaps together with a glass of fine port... It has long been in the museum collection and is of unknown provenance - the original wearer remains a mystery... |

#3 - The Perkin's Mauve Waistcoat, c. 1860

|

Worn in a Sussex village in the mid-late 19th century, this striking purple piece no doubt caught both the sun's rays and the eyes of many a passer by.

With shawl lapel, the waistcoat is flamboyantly synthetically dyed with mauveine, originally known as 'aniline purple'. The colour is complemented by the moiré/watered silk finish which brings out a fantastic sheen. The overall condition is excellent given the tendency of the dye to fade in light. This dye is of special note as one of the entirely serendipitous major discoveries of the 19th century. In 1856, an 18 year old chemistry student named William Henry Perkin had been set the challenge by his Professor to chemically synthesise quinine, the much in demand malarial treatment sourced only from Cinchona trees. Working at his home laboratory over Easter, his second attempt at this aimed to oxidise aniline sourced from the plentiful coal tar of the time by reacting with potassium dichromate. Upon later cleaning the flasks with alcohol, Perkin noticed that a distinct purple residue was created. By 1857, a patent and investors had been secured and a factory built in Ealing. A purple craze ensued, at its height from 1859-61. The fashion forward could now wear something similar to the Tyrean Purple of antiquity, sourced only from murex sea snails - but in a comparatively affordable, if far less colour-fast artificial form. By the end of the decade, fashion had moved on to new artificial colours created by the industry seeded by this, the very first synthetic dye. Also seeded - the pharmaceutical industry. As for Quinine? It would not be finally synthesised until 1944. |

Who wore it?

The museum database entry notes the owner as 'Mr. Frost, Corn Chandler, who had a shop on site of Brazier's Garage' and the waistcoat appears to have been altered to shorten. As of 2021, this is the site of the Shell Garage on Golden Square. It entered the collection in 1979, donated by a family member. One possible candidate is William James Frost, who was born in Berkshire in 1825. His occupation was listed as grocer in the local business directories in 1851, '59, '66, and '78 in addition to the censuses of the time, but the 1859 directory also lists him as a draper. Could this waistcoat have been a showpiece for a business venture that didn't last? However, it must be noted that corn chandler is not mentioned.

Another possible use may well have been at meetings of a local social club or society - Henfield had many at the time. 1890 found a most likely retired Mr. Frost living at 'Glen Avon', a fairly large detached house built at Nep Town in the 1880s or early '90s.

The museum database entry notes the owner as 'Mr. Frost, Corn Chandler, who had a shop on site of Brazier's Garage' and the waistcoat appears to have been altered to shorten. As of 2021, this is the site of the Shell Garage on Golden Square. It entered the collection in 1979, donated by a family member. One possible candidate is William James Frost, who was born in Berkshire in 1825. His occupation was listed as grocer in the local business directories in 1851, '59, '66, and '78 in addition to the censuses of the time, but the 1859 directory also lists him as a draper. Could this waistcoat have been a showpiece for a business venture that didn't last? However, it must be noted that corn chandler is not mentioned.

Another possible use may well have been at meetings of a local social club or society - Henfield had many at the time. 1890 found a most likely retired Mr. Frost living at 'Glen Avon', a fairly large detached house built at Nep Town in the 1880s or early '90s.

Images on this page are licensed for educational and non commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) . Please credit 'Henfield Museum' and contact us if you would like to use an image for commercial purposes or at a higher quality.

Website funded by the Friends of Henfield Museum, built & maintained by R. S. Gordon. Credit to Mike Ainscough for moving the website idea from discussion to reality.

© Henfield Museum. All rights reserved except where stated otherwise.