|

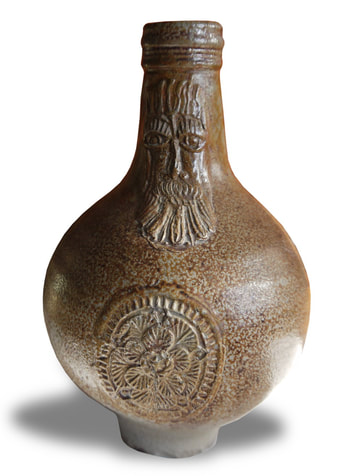

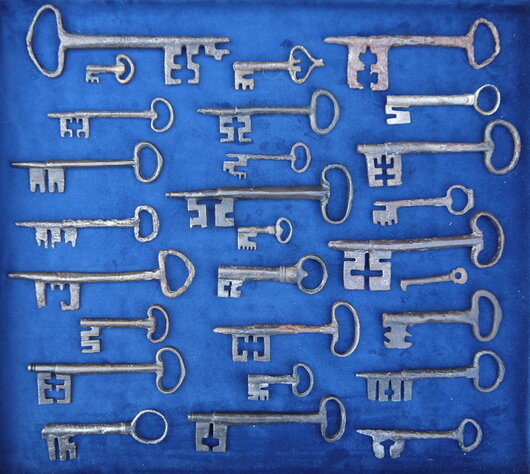

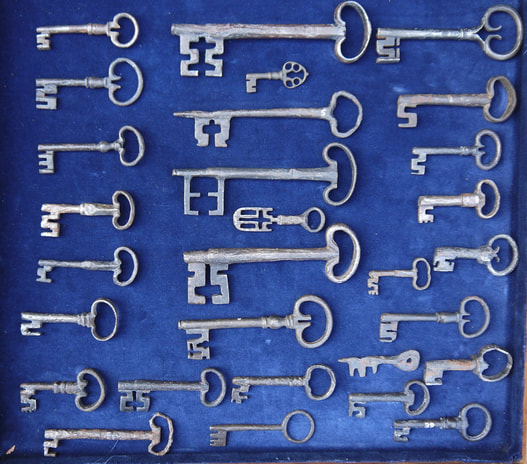

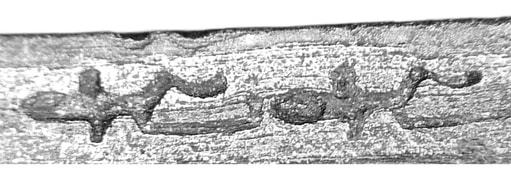

This article was first published in Treasure Hunting Magazine in October 2020 and is published here with the kind permission of the author Jason Sandy to support the temporary Henfield Museum exhibition 'The Thames Mudlark', on show until December 2020. Mudlarking Requirements Please note: in order to go mudlarking in London, a Thames Foreshore Permit must be obtained from the Port of London Authority. Check their website for full details. Digging, scraping, and metal detecting are restricted or prohibited in some areas. All objects which are 300+ years old must be reported to the Museum of London for recording on the British Museum's Portable Antiquities Scheme. Introduction Imagine digging a deep hole and finding a beautiful, perfectly preserved medieval knife (Fig.1). Now imagine collecting 860 medieval and post - medieval knives while mudlarking along the River Thames. That's exactly what veteran mudlark, Graham duHeaume, has done during his 16 years of searching along the foreshore in London! Graham, who turns 83 years old this year, has amassed an astounding collection of historical artefacts, some of which are on display in various museums around Britain. His passion for mudlarking was sparked back in the 1950s when he heard Ivor Noël Hume speaking on the radio during an interview on BBC Children's Hour. Ivor wrote the legendary mudlarking book, Treasure in the Thames and was an archaeologist at the Guildhall Museum (London) as well as being the chief archaeologist and director in the Colonial Williamsburg (USA) archaeology programme. During the radio broadcast, Ivor described how he walked along the north bank of the Thames in the City of London and dis covered medieval pins, clay pipe bowls, pottery sherds, coins and many other artefacts. Graham first heard of the term 'mudlark' on the television show called 'Animal, Vegetable and Mineral'. During the broadcast the noted archaeologist Sir Mortimer Wheeler told the story of Billy and Charley, notorious mudlarks in the 19th century who produced many fake medieval artefacts, claiming they were from the Thames. First Mudlarking Exploits In 1969, Graham first tried mudlarking for himself. According to Graham, "I first wrote to the Port of London Authority in late 1969 asking them for permission to search the foreshore. They replied saying that they had no objection as long as I refilled any holes I made. Those were the rules in those days. In early 1970, I convinced a friend of mine to accompany me. Of course, like the early radio broadcast, I came home with pipe stems and bowls, pins, pot sherds and guess what? A broken knife! I was heady with excitement and wanted more. This was a symptom of 'Thamesitis', a condition well known by today's mudlarks. I started with a shovel and it was a case of small excavations, a bit of checking the spoil and wandering around eyeballing at low water. It soon became apparent that you could tell if you were on undisturbed strata. So, the deeper you dug (Fig. 2), the older the pieces. It was a progression through the periods. This was where the ironwork was in exceptionally good condition. I didn't have a metal detector in the early days, that would come later. I used to work in tandem with a friend, Martin Brendell, who also worked at the museum. I often went during lunchtime for a quick eyeball. I remember with pleasure my lunchtime forays with Simon Moore and my searches near Queenhithe with Peter and Martin and all the other erstwhile mudlarks, such as Tony Pilson, the Smith brothers and Peter Elkins (Fig.3). There were many other folk on the foreshore who contributed in some way or another to the advancement of knowledge relating to life on the river. My mudlarking experiences in these days certainly enhanced my appreciation of history, especially that of London." In 1966 Graham started working at the Natural History Museum and was surrounded by many collectors. As the Head of the Technical Services Department, Graham worked for 5 years at the International Institute of Entomology situated in the Natural History Museum. He was responsible for sorting large collections of insects, illustrating technical papers with insect drawings and the identification of Thysa noptera (Thrips), Graham explains that "Having worked at a museum which is one large collection, it's not surprising that the environment I was in encouraged my desire to be a collector. After searching along the Thames from 1970 to 1986, Graham (Fig. 4) retired from mudlarking and moved away from London. Subsequently, he has spent countless hours carefully recording and documenting each piece in his collection. In this article, Graham gives us an exclusive insight into his extraordinary collection of fluvial treasures from both the River Thames in London and River Avon in Salisbury. Bellarmine Bottle During the 16th - 17th centuries, Germany exported large quantities of pottery to London. The popularity of German stoneware is demonstrated by the vast amount of sherds recovered from the Thames foreshore. Occasionally, mudlarks find fragments of strange bearded faces, but Graham is one of the few lucky mudlarks who have found complete 17th century Bartmann jugs (Fig.5). Nicknamed after Cardinal Bellarmino who tried to ban alcohol, Bellarmine jugs were a type of decorated, salt - glazed pottery produced primarily in Frechen and Cologne. The bearded facemask appeared on the neck of the vessel along with a medallion or 'cartouche' on the belly. Dated to 1650-1670, Graham's jug here is decorated with a beautiful floral medal lion. Fragments from these German bottles are common from the Thames, but complete ones are extremely rare. Our Lady of Tombelaine Pilgrim Badge Graham has discovered several medieval pilgrim badges in the Thames, but the badge shown in Fig.6 is one of his best ever finds. He found it while searching with Martin Brendell in the River Avon in Salisbury. It is a pilgrim badge of Our Lady of Tombelaine which was identified by Brian Spencer, the former Keeper of Medieval Antiquities at the Museum of London. In her right hand the virgin holds a lily signifying purity, while the left hand of the holy child holds an orb, representing the universe. Tombelaine is a small island off the Normandy coast of France (near Mont Saint - Michel) which was a popular pilgrimage destination in the Middle Ages. An English pilgrim must have travelled to France and brought the badge back to Salisbury before dropping it in the river. Graham and Martin donated this badge to the Salisbury Museum and it is featured on the cover of their Medieval Catalogue. St Christopher Pilgrim Badge One of Graham's most extraordinary finds is a medieval pilgrim's badge of Saint Christopher (Fig. 7). It is the first St Christopher badge ever found on the Thames foreshore, and Graham donated it to the Museum of London where it is currently on display in the Medieval London gallery. According to the Museum of London, “ St Christopher was thought to protect travellers, and also gave protection against sudden death and plague. People believed that those who looked on his image would not die that day, which made him a very popular saint. The saint is shown leaning on a staff and looking round at the Christ Child, who he is carrying on his right shoulder. Christ is holding the orb of sovereignty in his left hand and holds his right hand out in blessing. This is the scene of the most famous part of the story of St Christopher whose job was to carry travellers across a dangerous river. One day he carried a child across who was so heavy that he could hardly bear the child's weight. The child told him that he was Jesus Christ and that he was heavy with the weight of the world." How fitting that Graham found the badge in a river! It is featured in Brian Spencer's book, Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges. St. Thomas Becket Pilgrim Badge Many pilgrim badges found in the River Thames represent Saint Thomas Becket, the former Archbishop of Canterbury who had fallen out of favour with King Henry II. In AD 1170, four knights associated with King Henry murdered Becket in Canterbury Cathedral, and he quickly became a highly respected saint. Canterbury was one of the most important pilgrimage destinations in medieval England. Written between AD 1387 and 1400, Geoffrey Chaucer's famous book, The Canterbury Tales, describes a group of pilgrims who exchange stories as they walk from London to Canterbury during a pilgrimage to visit Becket's shrine in the cathedral. The pilgrims often bought inexpensive pewter badges of Becket as souvenirs to take home with them and Graham found one of these 14th - 15th century Becket badges which he kindly donated to the Henfield Museum (Fig.8). Satirical Badge In the middle ages, satirical badges were produced to show "disapproval of the established order by parodying reality and by poking fun at hypocrisy and human behaviour generally, especially in the upper strata of society" explains Brian Spencer in his book, Pilgrim Souvenirs and Secular Badges." The medical profession was one of the most common targets of medieval satire and complaint. In the church of St Mary, Bury St Edmunds, a late 15th century roof - boss takes the form of an ape with a urinal, the universal emblem of the medieval physician. These burlesque images travelled downwards into the field of popular culture, explains Brian. In the 1980s, Graham found a wonderfully comical 15th century pewter badge depicting an ape standing on a fish and urinating into a mortar that rests on the fish's head (Fig. 9). The ape holds a long - handled pestle which he uses to stir or pound the contents within the mortar. It clearly illustrates what people thought about doctors and their wild concoctions in the 15th century! Seal Matrix Ring A medieval seal matrix ring (Fig.10) was found by Graham and Martin Brendell on the bed of the River Avon in the City of Salisbury in 1981. After hearing the local Council had drained part of the river for bank repair, Graham and Martin went to Salisbury to go mud larking along the River Avon. Made of silver, the band of the ring is decorated with twisting ribs, A shield surrounded by a circular dot motif is engraved with three bird's heads (probably ravens). They donated the ring to the Salisbury Museum. Iron Horseshoes While digging on the foreshore, Graham has discovered several 13th - 14th century horseshoes (Fig. 11). Graham explains that "The bulges on the sides of the shoes suggest that the nail holes were punched whilst the shoe was still hot after being forged. Later horseshoes have smooth edges." Before cars were invented in the late 19th to early 20th century, horses had been the key means of transportation for millennia. Because of the long distances the horses travelled, carrying goods or pulling wagons, it was important to protect their hoofs from injury on the uneven, cobbled streets of London. Horseshoes provided the necessary protection. Thanks to the oxygen - free mud of the Thames, the iron horseshoes found by Graham are in extraordinary condition considering their age. Medieval and Post - Medieval Keys Over the years, Graham has found over one hundred medieval and post - medieval keys in the River Thames. The anaerobic mud perfectly preserved the ironwork and Graham has carefully and lovingly restored them. In Fig.12, some of Graham's best 15th and 16th century keys are presented in a display case. More 16th and 17th century keys are shown in Fig.13. The creative designs and unique shapes of these medieval and post - medieval keys are absolutely beautiful. Just imagine what doors and locks these keys opened in London centuries ago! I wonder what valuable goods were protected behind those heavy timber doors, secured with their robust Iron locks? Tudor Dress Hooks Brass clothes hooks became fashionable in Britain during the 16th century. The fasteners were used for a variety of purposes, mainly to hold clothing in place. Tudor women often wore a large neck scarf, and hook fasteners were used to secure the scarf to the garment below. They were also used in pairs to keep a woman's long dress out of the dirt as she walked through the streets. Graham has found several of these ornate dress hooks made of copper - alloy (Fig.14). The fasteners were beautifully decorated with openwork patterns, floral designs and abstract geometrical motifs. The wonderful designs illustrate the creativity of the Tudor craftsmen and their attention to detail. Post - Medieval Spoons Graham has discovered several complete spoons while mud larking (Fig.151). Four of the pewter spoons are from the 16th century and are decorated with a ball knop, baluster knop, seal knop and diamond knop. He has also found a 17th century slip top spoon and a brass trefid Cromwellian spoon from c.1680. You can imagine a sailor eating his morning porridge with one of these spoons as he was watching the sun rise over the Thames. Distracted by the passing ships and buzzing activity along the riverfront, he possibly dropped the spoon in the river accidentally. Post-Medieval Forks Along with his unparalleled collection of knives, Graham has also found some exquisite, complete post-medieval forks while mudlarking along the River Thames (Fig.16). On land, the bone and timber handles of the forks normally don't survive, however, in the dense mud of the Thames these delicate handles have been perfectly preserved. Many public houses, taverns and inns were located directly along the River Thames in London, and they served food to the countless sailors, dockworkers, lightermen, stevedores and other tradesmen who lived and worked along the river. It is possible that these forks were dropped in the Thames outside these venues. Love Token Made from a George Il halfpenny The love token shown in Fig . 17 was inscribed by hand with the words 'Mary Coombs Sept. 1729'. Was the token engraved by a sailor on a long voyage at sea? In his boredom he could have taken a common halfpenny coin and used his pocketknife to inscribe a beautifully detailed flower motif and his sweetheart's name into the surface of the coin as he was dreaming of returning to London to see her again. I wonder if the date is the day they met, got engaged or married? Pewter and Glass Brooch While mudlarking along the River Thames Graham found a lovely Georgian/Victorian brooch (Fig.18). Two flowers are formed with several pink glass stones surrounding white glass pearls. The flowers are fixed to a circular, pewter frame with incised decoration, accompanied by natural leaf patterns. Although Graham considers this brooch to be the least valuable item in his collection, he thinks it still has charm. Graham says "I regard this piece as Doxyware, a group of my own naming. Doxy is an archaic term for floozie, trollop, wench, minx and prostitute." Georgian Tankard In Central London Graham unearthed this beautiful, late Georgian tankard (Fig 19) at the bottom of a four foot hole he dug in the foreshore. Made of Britannia metal, it has a maker's mark and is dated 1826. The tankard was made during the reign of King George IV. The words 'Windsor Castle' have been engraved on a circular belt decorated with an ornate buckle and strap end (Fig.20). In the centre of the belt is the inscription, Victoria Station Pimlico'. Still to this day, there is a Windsor Castle pub located near Victoria Station in London which serves traditional pub food and a fine selection of lagers and ales. King George IV died in Windsor Castle (the royal residence in Windsor) in 1830, four years after this tankard was made. Webley British Bulldog Pistol As the tide receded in West London Graham's son discovered the gun shown in Fig. 21 under a bridge in West London. It's a 142 calibre Webley British Bulldog revolver, first produced in 1872 by Philip Webley & Son of Birmingham. In Victorian times, these pistols were popular because they were lightweight, portable and easily concealed. They could be purchased by members of the public. Because the gun was found under a bridge, it is highly likely that this pistol was purposely discarded in the river, possibly after a crime or murder? If only this pistol could talk, it would be fascinating to find out what happened! Knife Collection Graham didn't intend to start collecting knives, it just started naturally: "As I always say, most folk don't actually start to collect a particular item. It is only when you realise you've got more of one item than the others, you think oh! - I've got a collection. During my time on the foreshore, I noticed I was finding more knives than other pieces", he explains. Graham's knife collection comprises around 860 pieces which were all recovered from the Thames foreshore between 1970 and 1986. The knives range from the late 14th century up to the end of the 17th century. Graham has 110 complete scale tang knives from the 15th - 16th centuries, 94 knives from the late 16th - 17th centuries, 300 whittle tang scale knives from the 14th - 16th centuries and over 300 blades and part blades from the late 16th - 17th centuries. The seven knives shown in Fig. 22 are lovely examples from the late 15th and 16th centuries. Five knives are scale tang, and the bottom two are whittle tang knives. Some of the 17th century knives illustrated in Fig. 23 have beautifully decorated handles carved from elephant ivory, bone and brass. Each of these knives have a cutler's mark on the blade. Cutlers' marks were used for several decades, and the successive cutlers were in turn licensed to use that mark. The dating of these pieces is based on the cutlers listed during the style period of each piece, but it is often not possible to narrow it down to one name. For example, in Fig. 23, the dagger over anchor mark is from either Peter Bell (1640) or William Justice (1664); the cross and dagger mark from George Skuyt (1615); the triangle and dagger mark is from Benjamen Stennet (1688); the bunch of grapes mark is from William Balls (1627); the unicorn and dagger mark is from Peter Spitzer (1621); the trefoil mark is from Andrew Rose (1606) or Thomas Heddinge (1619), to name just a few. Of the 860 knives, about 795 blades bear a cutler's blade smith's mark (Fig. 24). Graham explains that "The origins of the bladesmith's mark go back to 1365 when King Edward III enacted that all makers of swords and knives mark their blades. This was an early quality control, since there must have been many examples of shoddy workmanship. These knives were recovered from deep in the Thames foreshore and were preserved in a strata which prevented oxidization. Consequently, the makers' marks are in remarkable condition. The marks are in various forms such as a star, crescent, fleur - de lys, crown, rose, sword and many other devices, some of which have not been identified. Unfortunately, there is precious little information as to the identities of the makers in the medieval and Tudor period." Simon Moore , who accompanied Graham on many lunchtime forays to the foreshore, wrote a book called, Cutlery for the Table, which is one of the most important contributions to the archaeology of cutlery in the United Kingdom. Some of the knives which appear in the book are from Graham and Simon's personal collections. The Worshipful Company of Cutlers At age 83, Graham has been contemplating what to do with his expansive collection of knives. He said that “There were only two options as far as I was concerned, the Museum of London or the Worshipful Company of Cutlers. In the end, I decided on the WCC as the makers' marks are more important to them." The Worshipful Company of Cutlers is an ancient livery company in the City of London which received its Royal Charter from Henry V in 1416. The Company was originally established to regulate trade and ensure the quality of the swords, knives and other cutlery produced in London. Located in a beautiful, historic hall near St Paul's Cathedral, the Company still exists and has active members who meet on a regular basis. Graham was invited (together with fellow mudlarks Monika Buttling - Smith and Nick Stevens ) to give a talk at Cutler's Hall and to display some of his amazing finds (Fig.25). At the end of the presentation, the chairman of the Company formally accepted Graham's donation of his knife collection (Fig.26). The Collection is Homed In February 2020, Graham received an official acceptance letter from Rupert Meacher, Clerk of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers. Rupert wrote: "I am writing on behalf of the Master and Company as a whole to express our huge gratitude for the most generous gift of your superb collection." When the letter arrived, Graham said he was thrilled - "The letter confirmed my decision to donate my collection to Cutler's Hall was correct. I am delighted they appreciate its contents. Graham, Monika, Adam and I were invited to a formal lunch at Cutler's Hall on 2nd March 2020 to honour Graham and acknowledge his generous donation. After a few glasses of champagne, we were served a three course meal including a delicious roast dinner in the Cutlers' oak - panelled dining room (Fig 27), warmed by a crackling fire. Rupert confirmed that they are in the process of acquiring oak display cases which will be installed in the entrance foyer to permanently exhibit Graham's knives for all to see. Graham, Monika and I have been invited to curate the knives within the display cases. This will be a lasting legacy to Graham's generous donation and his years of excavating and carefully restoring over 800 historic knives from the Thames foreshore. He has made a significant contribution to the archaeology and history of London and the River Thames. "It pleases me to think I have added an appreciable amount, especially to the world of cutlery. I think that the knives I have donated will improve the understanding of Cutlers' marks in general - The Worshipful Company of Cutlers will continue to research the knives in Graham's collection, which will educate and enthuse visitors, historians and academics for many generations to come. This is a true story about the ultimate goal of treasure hunting - the donation of an outstanding collection of historical artefacts to an institution which will protect and use the collection for educational purposes. If you would like to see Graham's knife collection, many of his knives will be on display in a mudlarking exhibition at Riverside Studios in Hammersmith, London as part of the Totally Thames Festival in September 2020.

by Jason Sandy First published in Treasure Hunting Magazine, October 2020.

8 Comments

|

We hope you enjoy the variety of blog articles on the people and places of Henfield past!

AuthorsArticles the copyright of their respective authors. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Website funded by the Friends of Henfield Museum, built & maintained by R. S. Gordon. Credit to Mike Ainscough for moving the website idea from discussion to reality.

© Henfield Museum. All rights reserved except where stated otherwise.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed