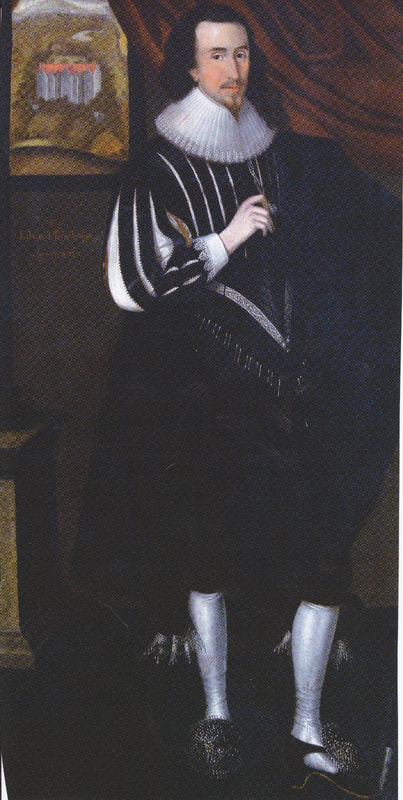

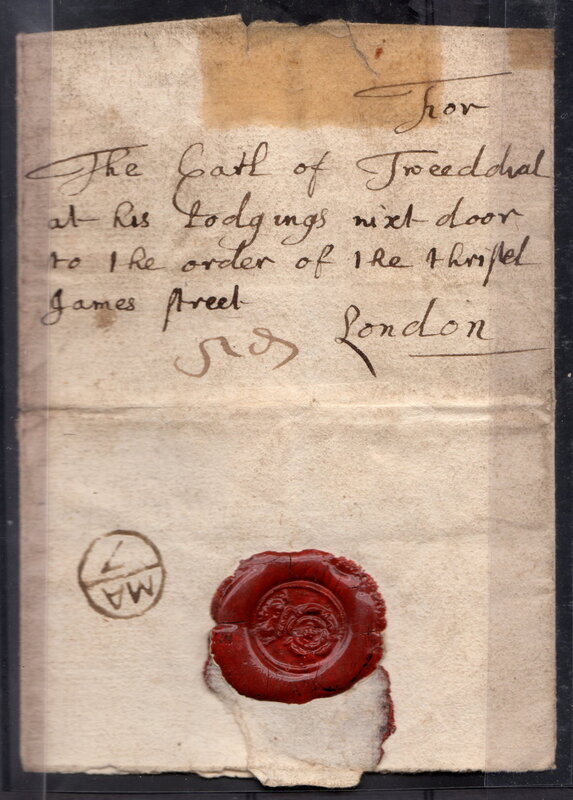

Henry Bishopp (1605 - 1691) Portrait by Francis Crake, 1684. Digitised from the portrait by R. S. Gordon, Henfield Museum, 2019 Henry Bishopp (1605 - 1691) Portrait by Francis Crake, 1684. Digitised from the portrait by R. S. Gordon, Henfield Museum, 2019 A loud banging echoed around Parsonage House and the heavy oak door shook on its frame. The dark had long since closed in on a cold January evening in 1644. Light from many torches cast flickering shadows, fitfully lighting the large Tudor house. King Charles had dissolved his final parliament and for not the first time in its history, the country was torn by Civil War. ~ The party of Roundheads had just galloped through Henfield High Street, a quiet village on the road to the coast. Their destination - the estate and home of Colonel Henry Bishopp. The younger brother of Sir Edward Bishopp of Parham - the black sheep of the family and a leading Sussex Cavalier in all senses of the word - Henry was thus not in a position to easily talk himself out of the situation. The royalist stronghold of Arundel had just surrendered on January 6th 1644 after a three week siege, but not before Edward had been overheard by a prisoner stating 'in a very 'malitious and threatening manner' that he would 'burne the towne of Horsham' (a Parliamentary stronghold) if the king ever arrived to relieve him... A throwaway comment? Perhaps, or from a man who had sixteen years earlier got away with the murder of a family friend in the street, perhaps not... Edward's estate was confiscated by parliament. Refusing to pay their fines, he was to die a prisoner in the Tower of London before the decade was out. ~ Casting aside the protestations of a household servant, the soldiers had ridden straight through the gatehouse, and now demanded that Colonel Bishopp give himself up. Hearing the disruption outside, Henry jumped from his chair. Another servant rushed in - the Roundheads were here! Moving quickly, he went upstairs to the master bedroom. Like the rest of the house, dark wooden panelling lined the walls there, with fine inlays above the fireplace. Built into the panelling was a cupboard... ~ This house had been built by Henry's grandfather Thomas Bishopp Esq., a prominent Tudor lawyer and attorney for the Bishop of Chichester, who had arrived in Henfield over a century earlier (in the phonetic fashion of time, the family name was spelled a multitude of ways, although Bishopp was most common for Henry). Taking an 80 year lease on the rectory estate from the Bishop, he determined to create a house worthy of his new wealth and status on the site of the older medieval parsonage. However, in the religiously riven England of the 16th century, Thomas held increasingly strong Catholic loyalties, as did by certain accounts his son (and Henry's father), Sir Thomas Bishopp, the purchaser and 1st Baronet of Parham. This younger Thomas had been accused of hiding Catholic recusants in Henfield. Of the two, one was responsible for the installation of a carefully hidden 'priest hole' in the cupboard next to the chimney... Henry went straight to the cupboard, a favourite spaniel following at his heels. Opening the door, pushing aside cloaks and shirts, he removed a floorboard and swiftly climbed down. Handing the dog down, the servant replaced the board, shut the cupboard door and darkness descended... Within moments, the sound of heavy boots reverberated throughout the house. Outside the bedroom raised voices sounded and the door burst wide. A Roundhead strode in, hand on sword. Glancing around, he noticed the cupboard. Pulling it open, he pushed the clothes aside to reveal...nothing but bare floorboards. Feet away, but a floor below, Henry stood, praying that the dog remained silent. The cupboard closed, the footsteps receded. Voices converged in the hall, then receded. The sound of hooves arose...and receded. Ten minutes later, the floorboard was removed and candlelight lit the priest hole. Henry climbed out, but this was too close a call and the time had come to leave Sussex. Meanwhile, the Parliamentarians, their mission unsuccessful, took consolation at the White Hart... Drastic measures were clearly necessary and the New World beckoned... News had spread amongst the Cavaliers that the governor of the colony of Virginia was sympathetic to royalist refugees. Acting swiftly, Henry set sail for Jamestown, a sea voyage that often took a gruelling 6 - 8 weeks. Having purchased an estate of 600 acres, he later doubled this by sponsoring eleven emigrants (9 men and 2 women), for each of whom he received fifty acres of land in Virginia: 'On the S. side of James River commonly called by the name of Lower Chipoak' - supposedly a reference to a Henfield location. This land was owned years earlier by William Powell (an early associate of John Smith of Pocahontas fame), killed during an Indian reprisal raid in 1622. Henry did not remain long and was not idle. The tide of the Civil War was not turning in the Royalists' favour - even Jamestown was eventually cowed. A mysterious and apparently all powerful petitioning letter was dispatched by Henry in 1645 to the Speaker of the Commons. From the Grand Assembly of Virginia, it expressed that it was 'the earnest desire of the Colony of Virginia' that Henry be given safe return! Doing so in 1646, Henry took the National Covenant to parliament and through unknown means but surely wide connections and string pulling, was able to pull off the unheard of feat of having his sequestered estate discharged to him without any fine whatsoever the next year! Perhaps a promise to sponsor the eleven emigrants influenced the letter? Confiscating royalist estates was a key way Parliament raised money. By comparison, his brother Edward was initially fined £12,300, or about £2.8 million today - although eventually reduced to £800 and never actually paid before his death. Ever farsighted, Henry was referred to in a history of the Commons as 'an active royalist conspirator during the Interregnum'... Which no doubt put him in an extremely good position upon the return of Charles II in 1660 - he was allowed to buy the extremely profitable role of Postmaster General for the entire kingdom - for £21,500 (i.e. £4.2 million today) annually. 'Whereas We have by Our Letters Patents under Our great Seal, constituted and appointed Our Trusty and Welbeloved Henry Bishop, Esq'e, Our Post Master General...' Charles R. 16 Jan 1660-1. Henry's gift to posterity was his invention of the postmark: 'A stamp is invented that is putt upon every letter shewing the day of the moneth that every letter comes to the office, so that no Letter Carryer may dare detayne a letter from post to post; which before was usual.' H. Bishop, 1661. Henry gave up the role in April 1663, four years before it expired - no doubt pressure was applied by those likely to benefit from a fresh appointment. After an eventful life, Henry died at the age of 86 on March 19th, 1691 (Julian calendar). His marble memorial tablet in the Parham Chapel in St Peter's Church, Henfield, states (translated from Latin): Henry Bishop AR A certain friend in uncertain times, Charitable, Hospitable, Urbane, Excellent, When, (by various adventures and many crises) He completed eighty six years, Old age at last exhausted, He was laid here amongst his ancestors, March 19th, A.D. 1691 Postscript. The Bishopp legacy still lives on in Henfield to this day via one of the country's oldest charities, the Elizabeth Gresham Trust. In her will, Henry's sister had bequeathed in perpetuity the rent from a certain field (since known as the 'Flannel Field') to go towards clothing the poor of the parish. Henry was one of the first trustees - his successors ensure that donations to local good causes are still given out annually by the trust to this day. As for Parsonage House, it was reduced in size after Henry's death, but remained with the descendants of the Bishopps until 1911, when finally sold out of the family.

References

J.W.F., Parham in Sussex (London, B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1947). Baggs, A.P. et al., A History of the County of Sussex: Volume 6 Part 3, Bramber Rape (North-Eastern Part) Including Crawley New Town, T. P. Hudson (ed.) (London, Victoria County History, 1987). Cooper, Esq., William Durrant, FSA, Royalist Compositions in Sussex, during the Commonwealth. Davidson, Alan, Coates, Ben, The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629, Thrush et al. (eds) (2010). Greer, George Cabell, Early Virginia Immigrants, 1623-1666 (1912, online transcript). Henning, Basil Duke, The House of Commons, 1660-1690, Volume 1 (1983). Nugent, Neil Marion, Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants (1934, online transcript). Shirley, Evelyn Philip, Stemmata Shirleiana (1873). Squiers, J. Granville, Secret Hiding Places - The Origins, Histories And Descriptions Of English Secret Hiding Places Used By Priests, Cavaliers, Jacobites & Smugglers (1934). Squire, John, Hudson, Peter, Three Hundred and Fifty Years of Dame Elizabeth Gresham's Charity 1661 - 2011, Private Print, Henfield, 2011. Various, Report from the Secret Committee on the Post-Office (1844).

1 Comment

|

We hope you enjoy the variety of blog articles on the people and places of Henfield past!

AuthorsArticles the copyright of their respective authors. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Website funded by the Friends of Henfield Museum, built & maintained by R. S. Gordon. Credit to Mike Ainscough for moving the website idea from discussion to reality.

© Henfield Museum. All rights reserved except where stated otherwise.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed