|

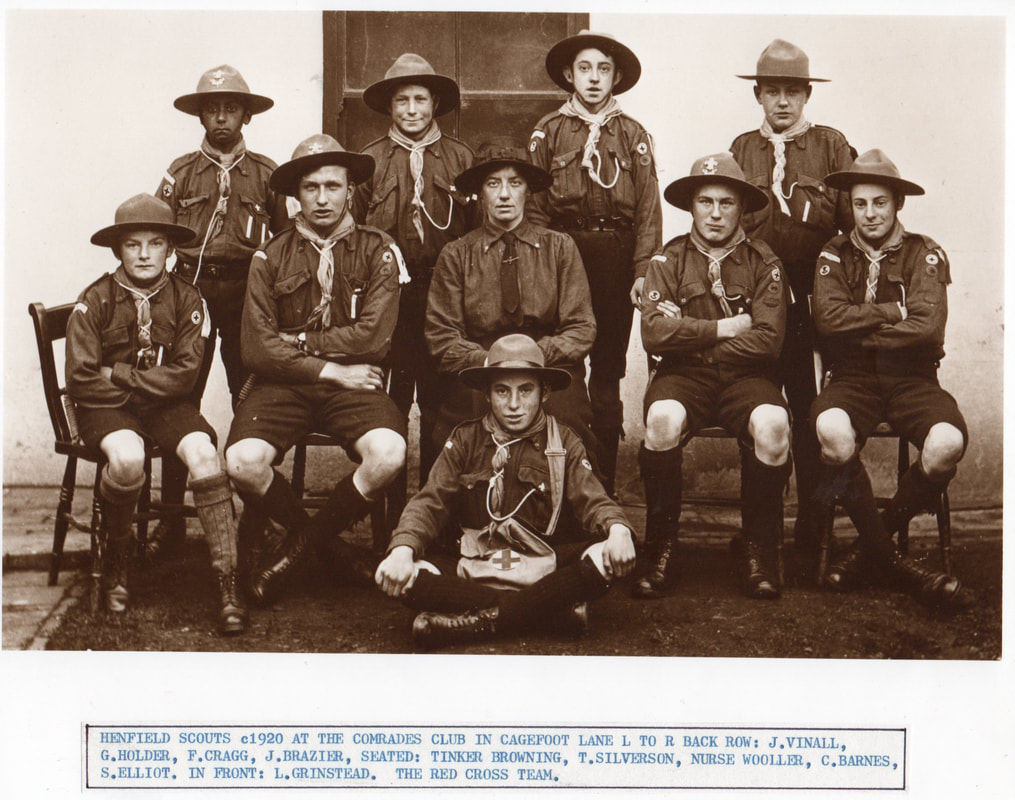

James William Vinall was born and lived his entire life in Henfield in the early 20th century. His paternal grandfather was reputed to be of South Asian descent, and he was known for having a distinctly Asian appearance, not something common in Henfield at the time and an early example of diversity in the village. He was very much part of the Henfield community, but his life was tragically cut short in 1945 due to extraordinary and harrowing events that took place while he served with the RAF in World War II. James’s early life and contribution to the community James (who more commonly went by the name Jim or Jimmy) was born on the 30 June, 1904. His parents, James Sr. and Fanny Vinall nee Browning, were also from Henfield. His South Asian ancestry is said to have come via his paternal grandmother, Jane Vinall, also originally from Henfield, who conceived his father while unmarried and working as a seamstress in France. Jim’s extended family owned the successful Henfield Vinall's Builders business and he and his father worked as builders for the company. He was very much involved with the Henfield community throughout his life. He played for the Henfield Cricket club from 1921 to 1939 and was also club secretary before the war. He played for the Henfield Football club and is seen in the photo below in the 1936/37 season, also being pictured with the Henfield Boy Scouts Troop c. 1914. At the Henfield Museum on the rear wall, you can spot him in the large photograph of the High Street (c. 1911), riding his bike as a child. He married Laurie Evelyn Vinall (née Lunnon) of Rottingdean. The ill-fated flight mission During World War II he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve, serving as Flight Engineer - despite being over the age where he would normally have had to serve on active combat missions. On the 14 March 1945, he and a crew of airmen were part of a specialised B-17 radar jamming squadron supporting a bombing attack on the German oil plant at Lutzkendorf (now part of the town of Braunsbedra). Their plane was hit by German flak and the engine caught fire. It seemed that the plane was going to crash so the pilot ordered his crew to parachute out. The pilot went to follow them but was caught up in oxygen tubing so was delayed. By the time he disentangled himself he was too low to safely bail out. However, the fire had extinguished itself and remarkably he was able to fly back to England safely, albeit without the others in the crew, including James, who had already bailed out - likely somewhat of a father figure to the crew at the age of 40, he had been the last to leave after checking that the rest had got out. Jim and the crew landed safely near the French border but were captured soon after by the Germans. Two members of the crew were separated and moved to a POW camp, but James and the remaining airmen were taken to a prison in Pforzheim, a region that had recently been heavily bombed. On their way there, they stopped at a village called Huchenfeld where they were to be held for the night in the boiler room of a school. As the region had recently been bombed and suffered heavy casualties and destruction, the population were no doubt very angry. An SA officer at a nearby village, Dillstein, heard the airmen were close and rallied the Hitler youth of the region to confront them. Jim and the crew were forced out of the boiler room and confronted by an angry crowd. Fearing for their lives, some of the crewmen tried to escape, causing a commotion. In the chaos, James and several others were able to escape, each in different directions. Sadly, though, four of the men were quickly rounded up and shot in the nearby cemetery. Jim was captured the next day and was briefly held in a police station in Dillstein, before being taken outside where he was beaten with a heavy stick until he collapsed. At this point a 15-year-old Hitler Youth member who had apparently lost his mother and five siblings in the bombing shot him dead. The other escaped men were also eventually recaptured but were held as POWs before being released at the end of the war. The case was tried by a war crimes tribunal after the war. The youths who shot the crewmen were given 15-year or 12-year jail sentences. But it was determined the Nazi officers and local officials who had instigated the killing and provided weapons were guilty to a more severe degree and three were hanged for their crimes.  James (far right) with the crew who would later take to the air in the B-17 Flying Fortress 'HB779 BU-K' at Blickling Hall, winter 1944-5. Photo by Dudley Heal (standing next to James): c/o 214 Squadron Association Reconciliation 47 years later, in 1992, the priest and several congregation members of the church in Huchenfeld, the German village where four of the men were killed, were so stirred by the terrible events that had happened, that they organised for a plaque to be mounted in the village church, memorialising the murdered crewmen. The widow of one of the crewmen who had been shot was present for a special church service. She had come in reconciliation and wanted to offer her forgiveness. During the service it is said that an older gentleman, full of sorrow, discreetly confessed to one of the clergy that he had been one of the young men who had shot at the crew. He then quietly slipped away from the service. The pilot of the ill-fated flight, who had survived by being able to fly back to Britain, was still alive and well at the time. However, he had not heard about the fate of his crewmen until he came across the story of the memorial. He was so moved that he commissioned a local artist from where he lived in Wales to create a rocking horse - 'Hoffnung' (Hope) which he gave to the children of the German village’s Kindergarten. The bond between the airmen’s families and the village community continued to flourish. In 2003, James's grandson was christened in Huchenfeld. In 2008 the pilot’s home village in Wales was twinned with the German village. It was another moving act of forgiveness, proving that reconciliation and hope are possible, even in the face of such terrible events as those that happened to Jim.  'Hoffnung' the rocking horse with German schoolchildren on his 25th birthday. Photo: Cambrian News, 18th Sept 2019 Conclusion The events that took place in March of 1945 led to a harrowing and tragic end for a remarkable man who held a central part of the Henfield community in the early 20th century. Nevertheless, forgiveness and hope did eventually prevail. When you next visit Henfield Museum, have a look on the mural for the little boy on the bike and you will know his story. Allison Dinnis, 2022 Many thanks to Adrian Vieler for sharing his research with me and to Alan Barwick of the Henfield Museum for bringing James Vinall’s story to my attention and helping me to find further information available at the museum. A version of this article was also simultaneously published in the November 2022 edition of BN5 Magazine. Key Sources - Peter Walker, ‘Hoffnung’ (Hope) - the rocking horse and the reconciliation between Llanbedr and Huchenfeld - the background story of friendship between former enemies', 214 (FMS) Squadron Association (2003) - Oliver Clutton-Brock, 'Footprints on the Sands of Time', Grub Street Publishing (2003) - Trevor Grove, 'Murdered by the Mob', Daily Mail (Saturday 21 December 2002) - The Henfield Museum Collection. For further information on James's story and that of the rest of his crew, see also the 214 Squadron Association website, searching the page for 'Vinall' or 'Flying Fortress Mark III HB779 BU-K' and the aircraft page on the Aircrew Remembered website.

2 Comments

|

We hope you enjoy the variety of blog articles on the people and places of Henfield past!

AuthorsArticles the copyright of their respective authors. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Website funded by the Friends of Henfield Museum, built & maintained by R. S. Gordon. Credit to Mike Ainscough for moving the website idea from discussion to reality.

© Henfield Museum. All rights reserved except where stated otherwise.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed