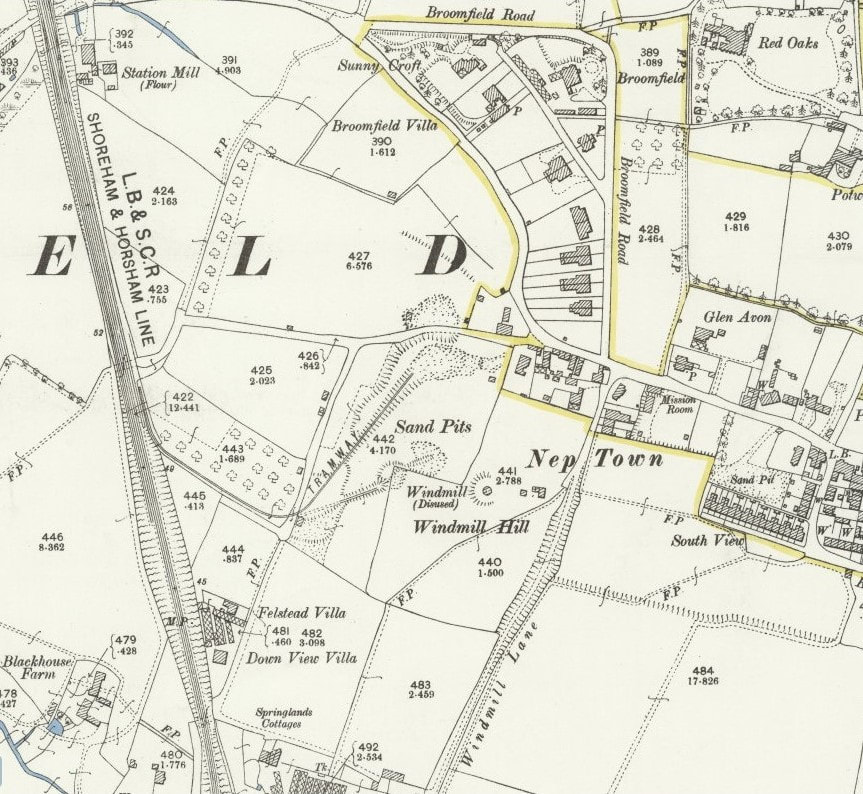

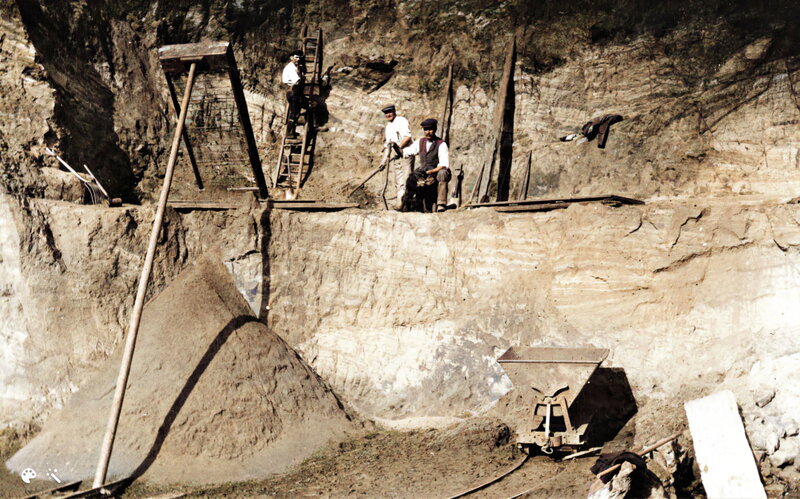

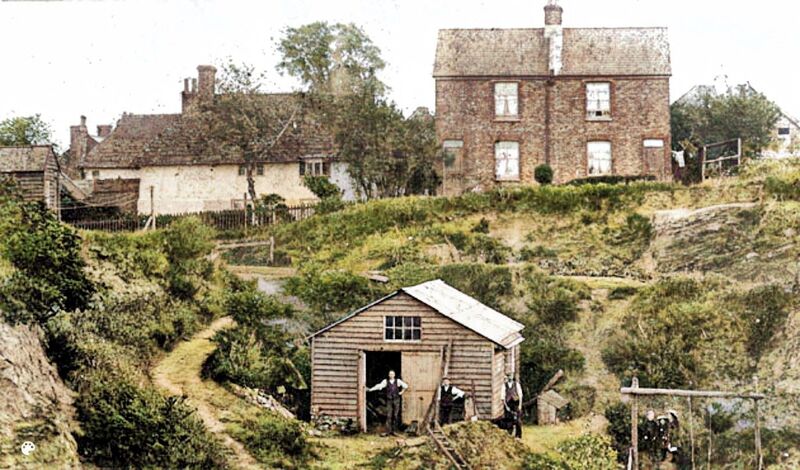

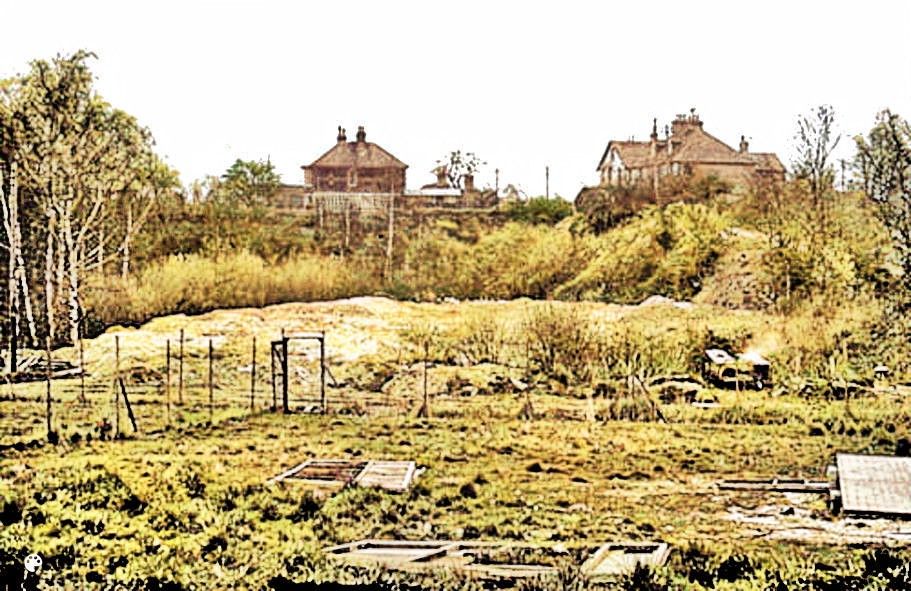

The long descending gully of the Henfield sandpit tramway, left foreman Bill Carter, right unidentified worker, c. 1912. Image: Henfield Museum (CC BY-NC-SA), colourised, 2020 As Nep Town windmill reached the end of its life with the Victorian era itself (finally collapsing in 1908), a new industry was firing and clanking up - the digging of sand. Henfield has had several sandpits over its existence, earlier pits being for limited local supply. The Sandy Lane pit was the most prominent, ultimately supplying large quantities of sand to the Brighton Corporation in the 20th century, playing an important role in Brighton's development. Windmill Hill was always a tempting place to dig, being itself a massive sandstone buttress on the edge of Henfield's sandstone ridge. Descend Sandy Lane and you will rapidly leave Henfield's sandstone, hitting the low lying brooks and floodplains of the River Adur. With an initial smaller excavation to the west of Sandy Lane in use by at least the 1870s under local builder Philip Hedgcock, by the 1890s, activity had greatly expanded to the east of Sandy Lane, with a pulley driven tramway having been put in place. With sand dug out by hand from the faces, it was first loaded into barrows which were dumped into the tramcars. Next sent on its way downhill via a long gully, it crossed the left hand fork of Sandy Lane heading on down to the London - Brighton railway line where an agreement for use of a siding was in place with the London, Brighton & South Coast railway. There a raised wooden platform allowed the tramcars to tip their load straight into railway trucks waiting on the siding. From whence it would be sent onwards, primarily for use in cement. For many years the foreman was William (Bill) Carter, born in 1867. He had moved up from Brighton in around 1900 and lived at Old Mill Cottage with his wife Alice, born at Henfield in 1863 and perhaps happy to return home. With the mill having fallen silent, its Horsham stone roofed house (now Grade II listed Old Mill House) still provided a heart to the activity in the area, with it and the neighbouring new cottages for the workers overlooking a large new pit next door! By 1901 Bill and Alice had two daughters; Nellie aged 5 and Ethel Rose aged 1 (two others had died in infancy). By 1911, Alice did not show on the Census and Nellie was a nurse of 15, with Ethel at school. Prior to moving to Henfield, Bill had been a stationary engine driver in Brighton, which would no doubt have made the construction and operation of the quarry tramway simple enough. He is shown on site in the photos below with two workers - their identities currently unknown - alongside family members. Philip Hedgcock died in November 1903, but in the preceding few years he had worked out an agreement with what was likely to have already been one of his main customers, the Brighton Corporation (forerunner of the council). The Brighton Borough Surveyor and the solicitors acting as Trustees to Philip's will had agreed that the sandpit, equipment and associated agreement with the railway would go on long term (35 year) lease to them at £600. As well as any profit going to the Trustees, a sixpence royalty per cubic yard of sand extracted would also be charged until the Corporation paid the sum off and took full ownership! From New Year's Eve 1905, the lease on the 'Mill House Sand Pit' became active. Having previously been the customer, the Corporation was now its own manager and supplier, with much of the sand going straight towards the 20th century expansion of the city of Brighton. By 1909, the pits, along with the tramway, had expanded towards Windmill Lane where the windmill's long overwatch of the Downs had recently ended. Occasionally, if Bill or another of the labourers were watching carefully enough, the pit would reveal secrets of the area's past. Truly ancient pygmy flints from the Mesolithic era saw the light, painting pictures of long ago groups of hunter gatherers congregating on this high point knapping their tools, surrounded by the untamed wild. This many millennia before the idea of nations, settled villages or arguably even the idea of the individual as we know it had arisen. Evidence of later activity came too - Roman pot, perhaps last used by an inhabitant of the province of Britannia, surveying the tamer lands of the coastal strip from what would many centuries later, become Windmill Hill. At their back, the vast Forest of Anderida stretched from the edge of whatever name the limited settlement where Henfield now stands once had, almost to the capital at Londinium. By the arrival of the 1930s, the pit was largely worked out. The last act came just before the Second World War when the field east of Windmill Lane was mechanically excavated from 1935-8, leaving a large pit and steep drops on both sides of the old, already sunken Windmill Lane. The north part of this new pit was then initially rented by the aptly named Greenfields for market gardening, with the south rented by David Stephens who ran a sawmill there. The pit is well evident today and now home to the house 'Sandpits'. An afterlife for the old hand worked pits came in the form of allotments to the south and a chicken farm to the west of the site, active until the removal of the railway in the 1960s - the foundations of the chicken huts are still well evident today. In recent decades, the former pit has returned to nature. With woodland having grown up across the site - the clamour of industry once having arisen, has now receded. R. S. Gordon, 2020 References - Barwick, A. & Carreck, M, Henfield: A Sussex Village (Chichester, Phillimore, 2002) - c. 1912 photo series (held by Henfield Museum) - Census returns - Old Mill House investiture, 1907 (privately held) - Oral recollections - Historic Ordnance Survey maps c/o the National Library of Scotland. - West Sussex Historic Environment Records: MWS3343 & MWS878 Gallery - Henfield SandpitAlong with the leading image above, these photos have been suggestively colourised and in some cases enhanced, as indicated by the bottom left corner graphics. The first set of five photos was taken c. 1912 and were donated to the museum by a grandson of Bill Carter (licensed under CC BY-NC-SA).

2 Comments

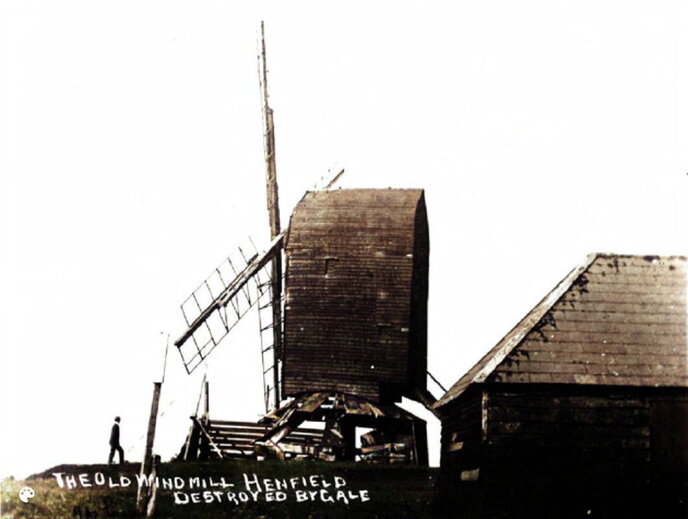

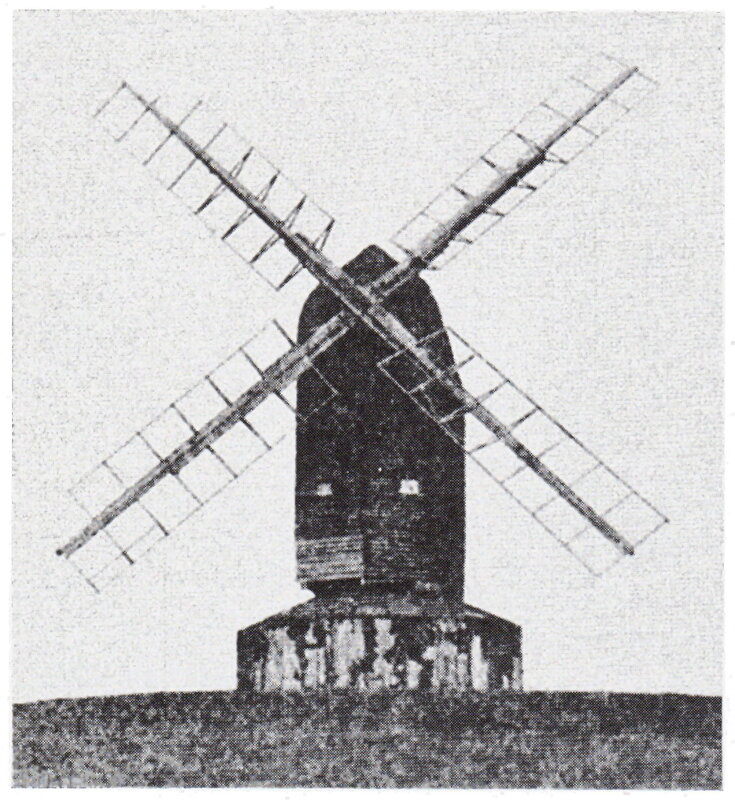

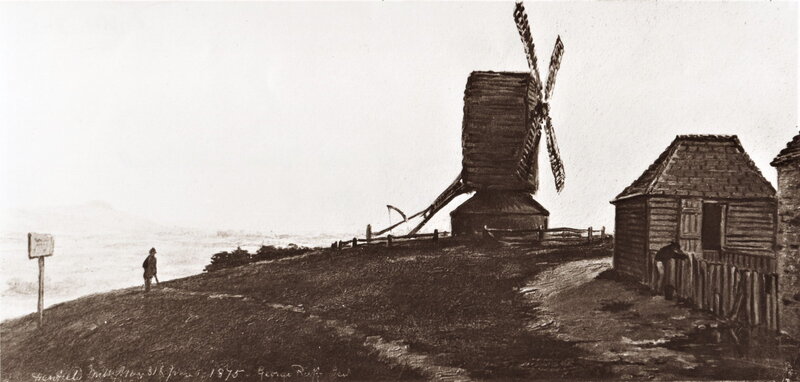

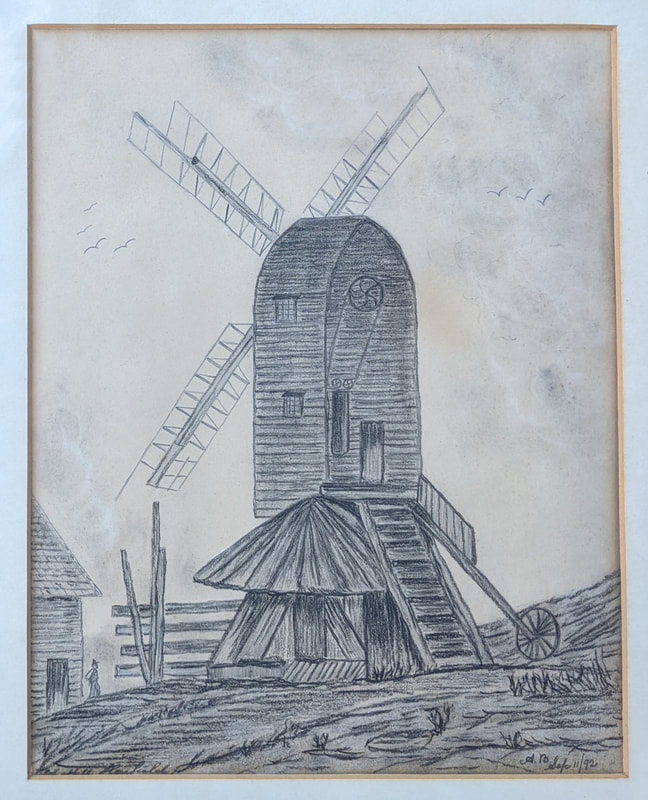

At the far end of the former hamlet of Nep Town, the sandstone ridge of the village descends to the River Adur flood plains below. Passing Mill End and Windmill Hill, the road curves down into Dropping Holms to the right and descends the ancient sunken lane of Sandy Lane at left. Over the centuries the area has been central to parts of Henfield's history - here we tell the story of what was once popularly known as Henfield Mill...  The Nep Town Mill, Henfield, c. 1890s. The barn was actually some distance closer to Windmill Lane and the photographer than it appears. Image: Henfield Museum (CC BY-NC-SA), colourised, 2020 This post mill was most likely first erected at some point in the 17th century - it probably takes a position as the second oldest of the Henfield windmills with another noted as existing in a field near the house 'Cannons' by 1575. Several 17th century sources refer to what is most likely to have been the mill on this prominent site, although it is not known when the Cannons mill ceased operating. For example, the Commonwealth Survey of 1647 refers to notable local landowner John Gratwicke of Shermanbury holding 'the Windmill house and lands'. The mill was definitively featured on Budgen's 1724 map of Sussex and also features on Yeakell & Gardner's 1778 map of the county, being a notable Henfield landmark for generations. But this was only a continuation of use of an ancient site, with finds of Mesolithic pygmy flints having shown that hunter gatherers once lived and worked at this high vantage point. It was commonly known as 'Henfield Mill' before the arrival of the 'New Mill' on the Common in around 1820, after which it tended to be known as the 'Old Mill' or 'Nep Town Mill'. A post mill body or 'buck' would be rotated on its post to allow its sweeps to face the prevailing wind direction - woe betide a mill facing the wrong direction in a gale! This meant that millers or assistants needed to be ready to turn the mill at a moment's notice if the wind got up from a new direction or if a storm arrived in the night. The turning pole with wheel attached at back to ease the job of rotation can be seen in the photos. Newer mills such as the Henfield Common windmill (built in 1820) were updated with fantails, which on post mills like these were attached to the ground wheel and automatically rotated the mill to face the wind direction. The veteran Nep Town miller at this time, Robert Loase, ran the mill and associated farm where his wife Mary ran the dairy. Shortly prior to the announcement of the new mill, he had recently had his worst year in a quarter century milling - so quite what came to mind when he heard the news of the upcoming competition may not bear repeating! As with many trades of the day, the fortunes of milling could turn as easily as the sails of the mill itself. Robert had willed the property to his daughter (via her husband), However, on his death in 1827, a £400 debt to local landowner (and botanist of note) William Borrer was still outstanding and Mary had no choice but to sell the dairy farm - the mill however, was kept in the family for now. A characterful c. 1865 painting (the first image in the gallery below) harks back to an earlier era in the windmill's history. By Nehemiah Vinall, it shows the mill when still active - perhaps the bearded sawyer shown was the miller of the day. It links into interesting and tragic events in the mill's history and it is suggested he painted it due to a family connection. His great great grandfather William Vinall (the Elder) had been a miller and Henfield churchwarden in the latter 18th century. His son - and Nehemiah's great grandfather William Vinall (the Younger) was also Nep Town miller. One sad and dramatic day in 1795, he was drawn into the milling machinery and killed - a stark illustration of a time when workplace safety was largely an individual responsibility. With the set price Corn Law debates of earlier in the century becoming a distant memory as free trade and large industrial interests won the day amidst the increasingly corporate and globalised industrial scene, small scale local production of the sort offered by Henfield's two windmills became less and less viable. Long time journeymen millers like James Randall originally worked at the Nep Town Mill, but switched over to the new mill on the Common as demand was squeezed. There however, his situation did not ease - he was now a widower with six children and a taste for beer. A taste which would ultimately lead to three months' hard labour at Petworth Gaol for embezzlement when it was discovered that he had only been recording some of the daily transactions in the day book, the others in his own purse alone... To make matters worse, direct local competition had arrived in the form of two steam mills in 1860 and 1874 - which would themselves succumb before long to the powerful forces of the wider economy. By 1871 master miller Richard Luff and his wife Harriett were living at the Mill House, with five children and son Richard also being noted as a miller. However, having been a steady source of flour for centuries, the windmill finally went out of use in ~1880 with either Clement Knight or John Sharp recorded as being the last miller (one perhaps gave the mill a brief resurrection). Papers of the time recorded a final drama before the end when a local lad jumped onto a sail, presumably aiming to ride it a short distance. However, his hand became caught and he was unable to dismount in time, being swept up into the air. The sails were stopped, but he fell from some height, luckily surviving, albeit with some bruising and no doubt a great deal of embarrassment. Its life of grinding corn over, the mill still provided a fine vantage point over the countryside. For Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887, numerous bonfires - between 20 - 30 - were apparently spotted by those watching from its steps. The mill itself was retained as a Trinity House (and village) landmark, but according to de Candole's history of Henfield it finally collapsed with 'a loud crash in a mighty gale' on Friday, February 21st 1908. By the time of the First World War a few years later, a correspondent seeking it out reported very little remaining on site. The hill it stood on is now in many places much reduced in height having been subsequently dug out during the excavation of the Henfield sandpits, with the area now being almost entirely wooded. However, the sandpits did offer a small postscript for the mill - in the same way as the prehistoric flints, Roman pottery was discovered. Perhaps, many centuries before, it had last been used by someone standing atop what would become Windmill Hill, looking across the Roman province of Britannia. Although going out of use at about the same time, the sole survival of the c. 1820 'New Mill' on Henfield Common for an additional forty-five years led to its having become much the better known of Henfield's mills today. R. S. Gordon, 2020 References Barwick, Alan., Carreck, Marjorie, Henfield: A Sussex Village (Chichester, Phillimore, 2002) Bishop, Lucie, Henfield in the News (Henfield, Private Print, 1938) de Candole, Henry, The Story of Henfield, (Hove, Combridges, 1947) Colgate, E. J., Henfield's 19th Century Egg Basket (Winchester, George Mann, 2020) Budgen's Map of Sussex, 1724 Yeakell & Gardner's Map of Sussex, 1778 Census Returns Sussex Mills Group Henfield Museum records West Sussex Historic Environment Records: MWS3343 & MWS878 Galleries - Nep Town WindmillPhotographs The limited number of known photographs of the Nep Town Mill are shown here (along with the leading colourised version in the photo above). This contrasts with the large number of surviving photographs of the 'New Mill' on the common. (Images from the Henfield Museum collection licensed under CC BY-NC-SA). Paintings & Sketches Luckily we also have a number of paintings and sketches from various artists in our collection which help to bring the mill back to life and provide information on the historic setting.

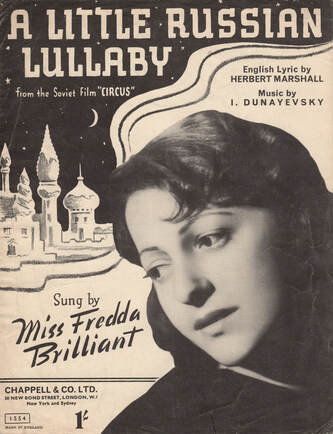

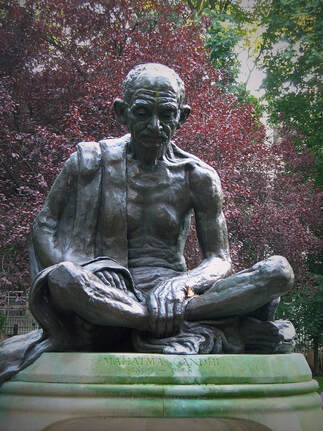

(Images from the Henfield Museum collection licensed under CC BY-NC-SA). An account by Peter Bates When we came to Henfield in 1969 the residents of Hole Farm Studio at Woodmancote were the sculptress Fredda Brilliant with her husband, film maker and translator, Herbert Marshall. Fredda sculpted many of the great figures of 20th century history, including Mahatma Gandhi and J. F. Kennedy. Her most famous statue, a 12ft bronze image of Mahatma Gandhi, stands in the centre of London's Tavistock Square. The project for the statue floundered and was saved in 1966 when the Labour Government stepped in with a grant of £4,000 towards the cost of £9,500. I remember giving them both a lift home after a jumble sale and being shown round the vast collection of small and large statues that there were in and around her studio. In the 1930s the couple lived in Moscow where Fredda, with no formal artistic training, cast in bronze many Russian film makers and authors, including Sergei Eisenstein and Anton Chekhov. She also sculpted Molotov for the Soviet Government. Fredda Brilliant, who died in 1999 aged 95 in Illinois, USA, was born into a Jewish family in Lodz, Poland. The family emigrated to Australia where Fredda became an actress and continued to act after emigrating to America in 1930. She also worked there as a scriptwriter and singer. She married Herbert Marshall in 1935 and they came to England in 1937, after their Soviet sojourn, managing to leave while the going was still somewhat good. After the war, in 1947, she played the lead opposite Michael Redgrave in Thunder Rock in London's West End, directed by her husband. From the late 1940s Fredda and Herbert spent much of their time in India where she sculpted a whole generation of Indian politicians and he made films for the Indian Government. From the mid 1960s the couple alternated between Illinois, where he was professor of Soviet Film and Literature, her London studio in Belsize Park and the converted barn studio in Woodmancote. Herbert Marshall died at Homelands Nursing Home in Cowfold in 1991. In an obituary in the Independent in June 1999, Patrick Reade writes that Fredda and Herbert returned to Sussex in 1989 and faced a bitter fight to reclaim their home from tenants and lived a very reduced state for many months. Doubtless folk will remember that 'she promenaded around the village of Henfield dressed in long black dresses, tasselled shawl about her shoulders and brilliant headscarf encircing her dark hair and small face - in winter she would wear a fur cost to the knees. With her emotions unleahed, her language let loose and her clothes trailing behind her, she became something of a local legend'. Text by Peter Bates, as first published in the Henfield Parish Magazine, 2020

|

We hope you enjoy the variety of blog articles on the people and places of Henfield past!

AuthorsArticles the copyright of their respective authors. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Website funded by the Friends of Henfield Museum, built & maintained by R. S. Gordon. Credit to Mike Ainscough for moving the website idea from discussion to reality.

© Henfield Museum. All rights reserved except where stated otherwise.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed