|

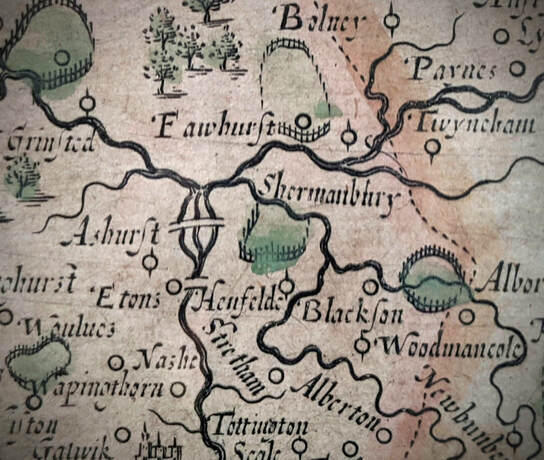

1661. A chilly autumn afternoon and the serving maid walked up a muddy and rutted Henfield High Street. Looking out across the open fields to the church, the Reeve's house and a scattering of cottages stood nearby. The large Parsonage House of Henry Bishopp Esq. loomed opposite and her employer Mr. William Holney's residence at Henfield Place was visible further off across the fields. All of Holney's five daughters would be well married within twenty years, but to the family's grief, the only son had died in infancy many years earlier, along with several other daughters. The high infant mortality of the day affected rich and poor alike. The little cottage to be known centuries hence by the name 'Rose' stood alone on Church Lane, chimney smoking, while picturesque gabled cottages stood either side of the junction. On the other side of the High Street lay inns, taverns, sturdy old hall houses, ramshackle cottages and small shops. Suddenly, a commotion echoed - amid loud protestations, the usual suspect was being forcibly ejected by the landlord of one of the village's tippling-houses - "Farewell thou sot! Don't return till what is owed is paid!". Several passers by took notice. Hurrying across the road, no doubt on God's work, Henfield's Pastor Rev. Richard Allen looked on with a grim glance of disapproval. He had taken on the benefice of St. Peter's three years prior after the departure of his Parliamentarian predecessor - the same memorable year his son had been born. Aside from the evident ills of popish recusants with their 'barbarous' ideas of transubstantiation and home grown schismatics like Quakers - 'a poor deluded people' - he could be well assured here of his oft strongly stated view that, 'drunkenness is the greatest eye-sore'. On the other hand, the windmill lad delivering flour to the White Hart had stopped completely, looking on with an amused stare of firm approval as the entertainment unfolded. Elsewhere, General Monck had marched south into London the year before, setting the cogs into motion for the return of the King, the end of the Commonwealth and the coronation of Charles II in April 1661. Further afield in Europe, many eyes were focused on the threat to Christendom from the Turks. Moving once more towards Central Europe, they would be at the Gates of Vienna for the final time before the century was out. Indeed, nine years later, villagers would be 'asked' by royal brief to contribute to a fund for Christian captives of the Ottoman backed Barbary Pirates in Algiers. But back at home, Henry Bishopp was the most prominent man Henfield had seen in a century. For his support of the royalist cause, he was newly appointed by Charles to the eminent position of Postmaster General - eyes looked on across the kingdom with envy. The war and Commonwealth had brought many changes, some lasting and some very temporary. Stretham Manor, part of the Bishop of Chichester's lands in the area had been expropriated to the Roundhead Sir John Downes, MP for Arundel, although tenants like Thomas Bellingham at Stretham farmhouse and George Rainsford at New Hall remained. On the King's return, Downes' head was soon detached, with the lands returned to the Bishop - and so to Henry Bishopp, whose family had held it on long term lease since his grandfather's time a century earlier. However, Henfield's Medieval deer park north of the village had fallen into permanent ruin after the Civil War - like many countrywide. With protection and funding removed, the park pales had been taken by locals for building materials, the deer eloped and the two ponds destocked. But, aside from the keepers, it can be guessed that most villagers cared little for the loss of this elite preserve. On the High Street, the drunken spectacle over, the maid approached a doorway and entered the establishment of Elizabeth Trunnell to a "Good day and welcome Miss!" Requesting the items needed, she reached into her apron, pulling out a copper farthing - or was it? Yes - but this was no general legal tender. While professionally minted, it served duty only in this shop. But Mrs. Trunnell would supply all that she needed today. In fact, in 1668, a newly minted local ha'penny would enter the financial fray - nearby shoemaker Thomas Pilfold likewise recognised the power of tokens and got in on the act. The Royal Mint was producing insufficient small change for the poor, so the tokens were officially tolerated. Eleven years later Charles II finally outlawed them, minting large numbers of his own ha'pennies and farthings in their stead.

These two trade tokens, donated by the Friends of Henfield Museum, can be seen in the museum's new medals, tokens and coins display - drop by and spot them! By R. S. Gordon. Article first published in BN5 Magazine, September 2021. More of the choice words of Henfield's Revd Richard Allen can be found in his three pamphlets, available courtesy of the Bodleian Library. To read further into both the Trunnell and Pilfold (sometimes spelled 'ford') families and the social and numismatic background of the tokens, see Geoffrey Barber's 2023 article published on this blog.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

We hope you enjoy the variety of blog articles on the people and places of Henfield past!

AuthorsArticles the copyright of their respective authors. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

Website funded by the Friends of Henfield Museum, built & maintained by R. S. Gordon. Credit to Mike Ainscough for moving the website idea from discussion to reality.

© Henfield Museum. All rights reserved except where stated otherwise.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed