|

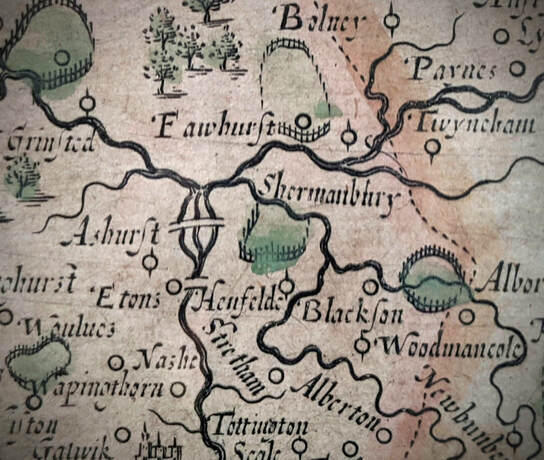

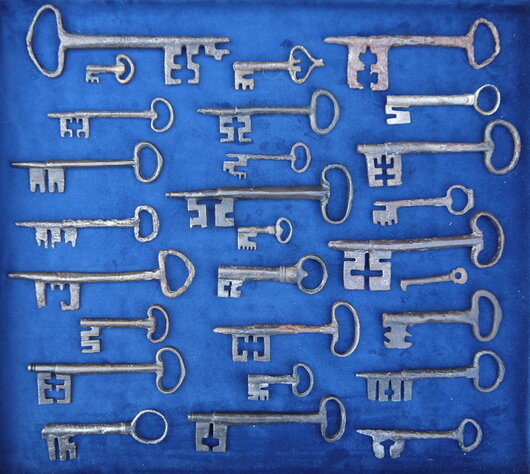

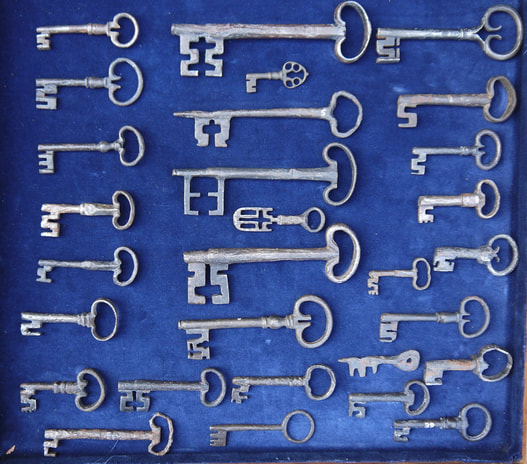

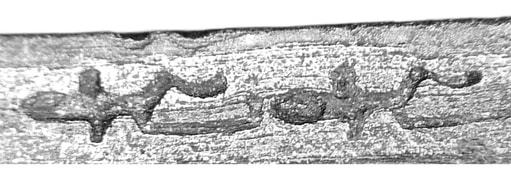

By Geoffrey Barber Abstract Two merchant tokens were issued at Henfield in the 17th century. Both merchants were mercers (clothiers) with Elizabeth Trunnell issuing hers in 1657 and Thomas Pilfold in 1668. It is likely that Thomas Pilfold took over the business from Elizabeth Trunnell, a widow who had contined to operate the mercer’s shop after her husband died in 1654. Thomas Pilfold was then succeeded by his son John who took the business well into the 18th century. The Pilfolds also owned a property called Hedgecocks at Henfield. In researching the token issuers, the extended family trees of both families were constructed and used with the many surviving wills to gain insights into their lives. Elizabeth Trunnell’s will shows a very comfortable living for the time and Thomas Pilfold’s will contains rare personal feelings and thoughts as he tries to deal with a wayward son. Both tokens can be seen at the Henfield Museum. Background During most of the 17th century there was a chronic shortage of small coinage in Britain. To address this, James I and Charles I licenced the manufacture of copper farthings to certain members of the aristocracy. Instances of underweight coins and refusal to redeem the farthings for “real” money created distrust amongst the public, and these licences were eventually withdrawn in 1644. The Civil War, which had started in 1642, then delayed the introduction of a proper solution which was to have an official regal copper currency. However, the merchants of England and Wales could not wait, so between 1648-72 they responded by issuing over 20,000 different base-metal farthing, halfpenny, and penny tokens so they could provide change to customers. Some of these would have been tradeable at the issuing merchant only, but others were widely accepted if it was known that the issuing merchant would honour their value. A number of towns even issued tokens for wider usage in order to facilitate trade amongst the poorer people, such as Midhurst in West Sussex (see Fig. 1). It wasn’t until 1672 that the official farthings, halfpennies, and pennies that we know today were finally introduced and the issuing of tokens banned. These merchant tokens are of great interest because they usually name the issuer, the town/village where they lived, and often identify the type of business they operated. Such tokens have been collected for over 200 years by numismatists, but it is only in our generation that the resources have become available to thoroughly research the token issuers and their families through online access to parish records, wills and archived documents. We are indebted to numismatists for their work in developing the knowledge about these tokens and for maintaining a market for serious collectors which has helped to preserve many of them. The standard reference work by Williamson was published between 1889 and 1891, itself a revision of William Boyne’s similarly titled original of 1858. Williamson’s numbering system is still used today to identify a particular token. Sussex BW96 (B[oyne]W[illiamson]96) identifies the token issued by Thomas Pilfold of Henfield in 1668, and Sussex BW97 identifies the token issued by Elizabeth Trunnell of Henfield in 1657. The leading reference today for 17th century West Sussex merchant tokens is the 2009 publication by Ron Kerridge and Rob de Ruiter[1], although much work remains to be done to properly research the many token issuers. Some 230 of these tokens have been identified in Sussex. This includes die varieties, so the number of different issuers is somewhat less than this. The relatively low number reflects the population and economy in Sussex towns and villages compared to places like London where about three thousand were issued. About one third of the Sussex tokens are undated, and among the dated the earliest to be issued was at East Grinstead in 1650 and the last in 1670 at Midhurst, Petworth and Steyning. The most common occupations of the Sussex token issuers were mercers (31 tokens), grocers (23 tokens), chandlers (16 tokens) and innkeepers (16 tokens). The Henfield Tokens There were two tokens issued at Henfield, a farthing token in 1657 by the widow Elizabeth Trunnell and a halfpenny token in 1668 by Thomas Pilfold, both mercers by trade. Mercers issued more tokens in Sussex that any other occupation and were the equivalent of the retail clothing trade we know today. In the big city a mercer would traditionally deal with silk and other imported fabrics and were regarded as the high-end clothing retailer. On the other hand, a draper would deal with general cloth as used by tailors to serve the wider community. But in a village such as Henfield, said to have had 400 adult parishoners in 1676,[2] many of these lines were blurred and the mercer would deal in linen, wool, and silk, incorporating the draper’s role and sometimes the haberdasher. To become a mercer required an apprenticeship and the cost of this could be substantial, so it was generally only available to the more well-to-do families (for example, Giles Watts who became a mercer at Battle was apprenticed to John Hanfield, a woollen draper in Ashford, Kent in 1710 at a cost of £45)[3]. Elizabeth Trunnell's Token, 1657 Elizabeth Trunnell was one of a number of widows who issued a token in Sussex. It was she and Alice Charmayne of Arundel who were the earliest to do so, at least in the tokens that were dated (about a third were issued undated). Her husband John Trunnell, a mercer, had died in 1654 leaving everything to Elizabeth[4], and her token shows that she was successful in keeping the business going. At that time, Elizabeth had five surviving children: Ann, John, Richard, Robert and Thomas who were all adults with only Thomas yet to be married. Records show that John became a mercer at Henfield, Richard a mercer at Hurstpierpoint, Robert a shoemaker at Henfield, and Thomas a barber-surgeon at Hurstpierpoint.[5],[6],[7] In 1657, when the token was issued, Elizabeth was probably operating the mercer shop at Henfield with the help of her eldest son John as there are records that show he was a mercer and living at Henfield.[8] Her second son Richard was working as a mercer at Hurstpierpoint, a village about 5 miles away. There is an undated farthing token that was issued at Hurstpierpoint by the mercer Thomas Donstall [Dunstall] with his initials T.P. The lack of an initial for his wife Elizabeth, who he married on 11 Jan 1659, suggests that it was issued before then. Thomas Dunstall also came from Henfield[9] and these common connections make one wonder if Richard was working for Dunstall and whether his experience at Hurstpierpoint influenced Elizabeth in her decision to issue her token, or vice versa. Sadly, Richard died in 1657, the year Elizabeth’s token was issued, at age 31 years. Something very interesting comes to light in the will of Thomas Dunstall’s brother, John, who wrote his will at Henfield on 13 May 1659, at the age of 25 years, stating that he is “sick in body but of good & perfect rememberance”. He must have been aware that he was going to die as he was buried just four days later. A witness to the will was none other than John Trunnell, eldest son of the widow Elizabeth, the token issuer. Surprisingly, he also died and was buried 15 days after witnessing the will, at 36 years of age. This was a tragedy for Elizabeth as she had lost Richard and now John, the eldest son, who was clearly positioned to take over the business. One is left to wonder if, in witnessing the will, John Trunnell also contracted the sickness that was afflicting John Dunstall. Smallpox comes to mind, a disease which can cause death, usually within 8 to 16 days of infection. It is a contagious disease, spread easily in a household setting, through the air or on objects like bedding and clothing. The deaths of Richard and John meant that there was no successor for the business, as her other two sons had not been trained as mercers. With Elizabeth an elderly woman, the opportunity was there for Thomas Pilfold to take over the business. His token was issued in 1668 indicating that he was established at Henfield by then. Elizabeth died in 1673, at about 80 years of age, and was buried at Henfield St Peter. Her youngest son Thomas had died two years earlier at 37 years of age and he had neither wife nor children.[10] She was survived by her son Robert Trunnell, the shoemaker, and her daughter Ann Jenner so it is possible that Elizabeth has descendants alive today who can claim a connection to her and her token. Elizabeth’s will deals mostly with her personal items, as any land or property belonging to her deceased husband would probably have been passed to her children long ago. In any event, her son Robert is left the residue of the estate so if there was anything not specified in the will, he was to receive it.[11] Elizabeth’s personal items show that she must have had a very comfortable living. Her will mentions three rooms in her house: a hall with a chimney, a separate lodging chamber and a milk house, and there were probably more. She is well endowed with beds, sheets, pillowcoats, blankets and towels; table cloths and napkins; pewter plates, platters, candlesticks and flagons; brass pots and kettles as well as furniture such as cupboards, chests for clothes of linen and wool, a small table at the foot of her bed, a gilt leather chair, stools, and bullrush chairs; an iron spit, pothanger, iron cleaver, tongs and gridiron; wooden bowls and platters; two velvet cushions, a carpet, hats, a gilt hat brush, a spinning wheel and a pewter chamber pot! The Trunnell Family While it was Elizabeth who issued the token it seems appropriate to mention her husband John Trunnell, who would have started the business at Henfield. The surname Trunnell is a local name and a variant of Trundle, possibly connected to a hillfort known as The Trundle at Singleton, West Sussex.[12] Unfortunately, the surname disappears from Sussex. There are no Trunnell entries in the Sussex Marriage Index after 1675 and none for Trundle/Trendle after 1739. The last Trunnell family left in Sussex in the 1500s were reasonably wealthy. In 1561, John Trunnell purchased Nyton farm in Aldingbourne, which still exists today.[13] It is his grandson John who became the mercer at Henfield. His father Robert died when John was about 8 years old, and in his will custody of John is given to Henry Potter, a preacher and brother-in-law: [14] “… to kepe him att School att some of the universities of this land and do allowe him for his mayntenance xijli [£12] yerely so long as he shalbe charged with my said sonne”. We know that John became a mercer with a business at Henfield, so it must have later been decided that an apprenticeship was the best option for him. He married Elizabeth Healy, the token issuer, on 27 September 1614 at Thursley in Surrey and they first appear at Henfield in 1616 when their daughter Elizabeth is baptised there. Five of their eight children grew to adulthood and all the male children were taught a trade. He died in 1654 at age 63 years, unaware of the sadness and disappointment that Elizabeth would later experience. Only their son Robert, the shoemaker who married and stayed behind at Henfield, was able to take the Trunnell surname into the next generation, but with no male heir his burial in 1710 is the last time we see the Trunnell name in Sussex. Thomas Pilfold’s Token, 1668 Thomas Pilfold’s origins are harder to trace than the Trunnell’s. He may have been born in 1632 at Billingshurst to Thomas Pilfold, a yeoman, but this is not certain. The earliest evidence of Thomas at Henfield is the baptism of his son Thomas on 14 Mar 1660 which gives the best estimate for when he took over the business.[15] While there is no record of his marriage,[16] he and wife Elizabeth had seven children, all making it through to adulthood. In 1668 he issued his halfpenny token at Henfield (Fig. 4) which shows the “Mercers’ Maiden” surrounded by the initials for Thomas and Elizabeth Pilfold. The “Mercers’ Maiden” (Fig. 5), taken from the Worshipful Company of Mercers’ coat of arms, was used on many 17th century tokens to identify the mercer’s trade. Thomas died in 1687 and his will expresses his desire to be buried inside the church at Henfield.[17] The will shows that he was greatly vexed by his eldest son Thomas whose inheritance was subject to: “whensoever it shall please God that he returns to his right mind, becomes dutiful & respectful to his mother & relations, & diligently follows his calling & employment”. Not wanting to disinherit his son, he gave the following bequests with conditions:

Trustees were appointed in the event that Thomas did not: “… behave himself dutifully to his mother & diligent in his calling” and if he should continue to “spend & by his negligence waste whatsoever he hath in his own disposing”. In that case he was to “stand to the Curtesy & Allowance of his mother, Elizabeth Pilfold my wife to whom alone I doe hereby give ye aforesayd house, goods & wares with all the appurtenances thereunto belonging to be solely at her disposing to all intents & purposes”. So, he was given a chance to redeem himself. It is not known what Thomas did during his life, but he died in 1737 at age 77 years and was buried at Henfield. His mother’s will made in 1713 does treat Thomas kindly, with a bequest of £6, some household goods and forgiveness of debts.[18] It was the second son, John Pilfold, who seems to have been the diligent and responsible person that Thomas had hoped to see in his eldest son. John became a mercer at Henfield, presumably continuing his father’s shop. He received the following bequest in his father’s will in 1687:

There are records of two apprentices that John took on: [19] 1 May 1713: William Fowle, son of Thomas (yeoman) of Albourne, apprenticed to John Pilfold mercer of Henfield. 3 February 1725: Peter Hill, son of Edward Hill of Woodmancote, apprenticed to John Pilfold mercer of Henfield.[20] John died in 1751 and his will shows him to be quite wealthy.[21] He had no male heir though, being survived by daughters Jane and Mary who both married well. It is not known who took over the mercer shop in Henfield, but it could have been one of the apprentices (the apprentice William Fowle was the son of John’s brother-in-law Thomas Fowle). John’s will shows that he held the copyhold property called Hedgecocks at Henfield, held of the Manor of Stretham. He passed this to his wife for the term of her natural life and then to his married daughter Mary Dennett, wife of John Dennett Esq. of Woodmancote He also left his house in Henfield to his his wife for the term of her natural life and then to his married daughter Jane Langrish, wife of Robert Langrish, apothecary of Midhurst. There is no mention of the Blackston Street property at Woodmancote that John inherited from his father. Conclusion All artefacts help to bring history to life, and the two tokens issued at Henfield are no exception. The issuers were prosperous merchants who nevertheless had to deal with raising a family, educating their children, coping with the mortality of their children and spouses, and even dealing with problem children as adults. They are the same issues that families have today, though thankfully we do not suffer the mortality rates they had in the 17th century. The tokens are a reminder of “Old Henfield” and rightfully deserve their place in the Henfield Museum. By Geoffrey Barber 7 July 2023 [email protected] References & Footnotes

Our grateful thanks go to Geoffrey Barber for his submission of this article for publication via Henfield Museum. For a picture of Henfield at the time the tokens were minted, read our 2021 article written on our acquisition of these tokens. All wills cited have been transcribed and given to the Sussex Family History Group Wills Depository which currently holds over 13,500 transcriptions. Copies are freely available to members. [1] Kerridge R. and de Ruiter, R “The Tokens, Metallic Tickets, Checks and Passes of West Sussex, 1650-1950”. (2009) [2] Sussex Archaeological Collections, Vol 45, “A Religious Census of Sussex in 1676”, p.144 [3] Sussex Record Society, Vol 28. (1924) “Sussex Apprentices and Masters 1710-1752”, p.20 [4] Will of John Trunnell the Elder, Mercer of Henfield, Sussex, England, made 10 Jul 1654, proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 16 May 1655. (TNA: PROB 11/245/247). [5] Will of Richard Trunnell, Mercer of Hurstpierpoint, Sussex, England, made 3 Aug 1657, proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 19 Sep 1657. (TNA: PROB 11/267/456). [6] Deed of Feoffment, 28 Mar 1670. (ESRO: SAS-EG/111) – refers to Robert Trunnell as shoemaker and Richard Trunnell his brother as mercer. Also refers to deceased brother, John Trunnell as mercer. [7] Will of Thomas Trunnell, Barber Surgeon of Hurstpierpoint, Sussex, England, made 21 Dec 1670, proved in the Archdeaconry Court of Lewes, 14 Jan 1671. (ESRO: PBT 1/1/32/124). [8] Deed of feoffment, 28 Mar 1670 (WSRO: SAS-EG/111) - shows that John held land at Henfield. He was also buried there on 28 May 1659. [9] Thomas Dunstall was baptised 18 Dec 1633 at Henfield, son of John and Elizabeth Dunstall. The will of his uncle Thomas Dunstall of Henfield, proved 31 Jul 1660 (TNA: PROB 11/299/784) and brother John Dunstall of Henfield, proved 27 Jun 1659 (TNA: PROB 11/293/515) confirm this. An interesting fact is that Thomas Donstall’s son became the Rev. John Donstall who was rector at Newtimber (1687-1733) and South Stoke (1706-1733). [10] Will of Thomas Trunnell, Barber Surgeon of Hurstpierpoint, Sussex, England, made 21 Dec 1670, proved in the Archdeaconry Court of Lewes, 14 Jan 1671. (ESRO: PBT 1/1/32/124). [11] Will of Elizabeth Trunnell, Widow of Henfield, Sussex, England, made 20 May 1673, proved in the Archdeaconry Court of Lewes, 20 May 1674. (ESRO: PBT 1/1/34/6C). [12] The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland (2016) [13] Bargain and Sale (unenrolled), 14 Jun 1561. (WSRO: ADD MSS/13135) [14] Will of Robert Trunnell of Bosham, Sussex, England, made 12 Oct 1598, proved in the Archdeaconry Court of Chichester, 19 Dec 1610. (WSRO: Ep/I/27/STC II/Folder U-W). [15] This baptism incorrectly records the mother’s name as Mary. Subsequent baptisms have the mother’s name as Elizabeth. [16] There is a marriage of a Thomas Pilfold to an Elizabeth Wheeler on 5 Aug 1657 at Billingshurst. However, it looks like an older Thomas Pilfold as it states “Thomas PILFOLD, yeoman of this parish, Alderman City of Chichester. Elizabeth WHEELER daughter of Thomas WHEELER gent whose former husband was Mr NATT”. [17] Will of Thomas Pilfold of Henfield, Sussex, England, made 9 May 1687, proved in the Archdeaconry Court of Lewes, 17 Jun 1687. (ESRO: PBT 1/1/38/40). [18] Will of Elizabeth Pilfold of Henfield, Sussex, England, made 8 Jul 1713, proved in the Archdeaconry Court of Lewes, 3 Jun 1724. (ESRO: PBT 1/1/51/307). [19] Sussex Record Society, Vol 28. (1924) “Sussex Apprentices and Masters 1710-1752”. [20] It is interesting to note that Peter Hill is the grandson of Richard Trunnell’s widow from her marriage to Thomas Goffe in 1661. [21] Will of John Pilfold of Henfield, Sussex, England, made 13 Jan 1749, proved in the Archdeaconry Court of Lewes, 28 Mar 1751. (ESRO: PBT/1/1/58/353).

2 Comments

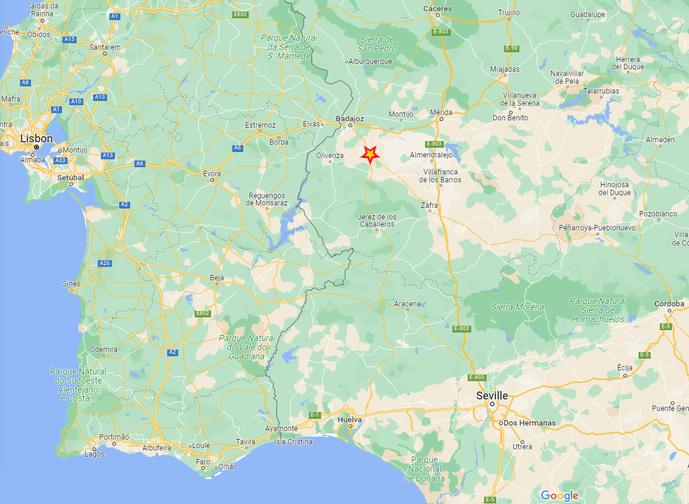

Tucked away in the storeroom in Henfield Museum is a box containing a brass regimental belt badge with the number 57, a laurel wreath and the name “Albuhera”. Being interested in regimental cap badges I did a bit of research and uncovered a very interesting story of one of the most brutal battles in the war against Napoleon, and a connection with Henfield! The badge belonged to a Daniel Caplin who was born in Woodmancote in 1786 and signed up to join the army in 1808. He was illiterate and his name was misspelt as Kepland or sometimes Keply. His army pay would have been 6d per day or 3d if sick. In 1810 he travelled to Jersey in the Channel Islands and then on to Portugal where he spent 2 days in hospital, and then marched to join Wellington’s Peninsular campaign. 35,000 British, Spanish and Portuguese soldiers under Field Marshal Sir William Beresford converged on the Spanish village of Albuhera. Facing them were 25,000 French soldiers under the renowned Marshal Soult, who was intent on relieving the besieged fortress of Badajos about 15 miles distant. Fierce and bloody, the pendulum of battle hung in the balance. The French feigned a frontal attack on the village and held the Allied army there, with their main force moving under cover of the high ground to assault the right flank of the Allied army. The Spanish fought with bravery, but began to falter under the onslaught of French musketry. Seeing what was happening an Allied division was sent to help the Spanish. A sudden torrential downpour rendered all the infantry muskets useless. Napoleon sent in the French/Polish Lancers who created their trademark chaos in the British lines; the battalions were decimated and the Regimental colours were captured. The 57th (with Daniel Caplin) moved up to support the faltering right flank. A lucky break in the weather allowed the redcoats to use their muskets again and they began raking the loose formations of rampaging enemy Lancers. In the panic and confusion some of the British unknowingly started to fire into the backs of the main British and Portuguese battalions, obscured by thick smoke. Colonel Inglis stood in front of his men commanding them to “order arms”. This act of courage saved many people’s lives that day. The 57th advanced to the front line and towards the mass of French infantry moving in their famed column of attack. Both sides fought to a standstill and the 57th were amongst the hardest hit. Colonel Inglis was hit in the neck and chest by French canister shot (a canister packed with lead shot that when fired from a canon burst in mid-flight scattering lead shot over a large area); he stayed on the battlefield and was heard to cry “Die hard, the 57th. Die hard!” The glory belonged to the 57th, but at a terrible price. Slightly varying figures are cited, but one example; of the 647 officers and men, 428 were reported as killed or wounded, a 66% casualty rate. Private Daniel Caplin was badly wounded in the left hip and arm and was taken from the battlefield to a hospital in Chamusca, Portugal where he stayed from 25th May 1811 until 10th January 1812. He was discharged and sent to England and rejoined the 6th Company 2nd Battalion from his bed in Hillsea Hospital. From that time on, the 57th was known as the ‘Die Hards’. Daniel married Anne Holder at Woodmancote on the 7th July 1813, his address was given as Chichester barracks. He was honourably discharged from the army on the 24th June 1814 and received the sum of 9d. He lived in Henfield with Anne and was classed as a labourer; he died in 1824 at the age of 38. I cannot imagine the horror that Daniel went through and only hope he was treated as a hero when he came home, and had 10 years of peace and happiness. Did he die at an early age because of the wounds sustained in the Peninsular War? It would be nice to commemorate him in some way. The 57th changed its name several times as regiments merged. It started as the 57th West Middlesex Regiment of Foot. In 1881 it became the Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge’s Own), then became the Queens Royal Surrey Regiment. It then became the Queens Own Buffs (The Royal Kent Regiment) and then the Royal Sussex Regiment, which is now part of the Princess of Wales’s Regiment. Steve Robotham (Assistant Curator, Henfield Museum). A version of this article was first published in the Parish Magazine, July 2021. Daniel's Albuhera belt plate is on display as of this article's publication. Sources:

From the Henfield Museum collection: - 57th Infantry Regiment of Foot cross belt buckle (2008/11) - Framed water colour painting of Pte. Daniel Caplin of the 57th West Middlx Regiment of Foot, in uniform of c. 1811, painted by Ray Kirkpatrick of Epsom Surrey in 2003 (2008/11/P1) - Maps (2008/11/P7, 2008/11/P6) - Brief typed history of Daniel Caplin (unpublished, 2008/11/P2) - Copy of 1814 discharge papers of Daniel Caplin (2008/11/P5) - MilitaryHistory.org, The Diehards - Regiment Profile, 2010 (accessed June 2021) - International Military Antiques, Original British Early 19th Century Cross Belt Plate from the 57th Regiment of Foot (accessed June 2021) 1661. A chilly autumn afternoon and the serving maid walked up a muddy and rutted Henfield High Street. Looking out across the open fields to the church, the Reeve's house and a scattering of cottages stood nearby. The large Parsonage House of Henry Bishopp Esq. loomed opposite and her employer Mr. William Holney's residence at Henfield Place was visible further off across the fields. All of Holney's five daughters would be well married within twenty years, but to the family's grief, the only son had died in infancy many years earlier, along with several other daughters. The high infant mortality of the day affected rich and poor alike. The little cottage to be known centuries hence by the name 'Rose' stood alone on Church Lane, chimney smoking, while picturesque gabled cottages stood either side of the junction. On the other side of the High Street lay inns, taverns, sturdy old hall houses, ramshackle cottages and small shops. Suddenly, a commotion echoed - amid loud protestations, the usual suspect was being forcibly ejected by the landlord of one of the village's tippling-houses - "Farewell thou sot! Don't return till what is owed is paid!". Several passers by took notice. Hurrying across the road, no doubt on God's work, Henfield's Pastor Rev. Richard Allen looked on with a grim glance of disapproval. He had taken on the benefice of St. Peter's three years prior after the departure of his Parliamentarian predecessor - the same memorable year his son had been born. Aside from the evident ills of popish recusants with their 'barbarous' ideas of transubstantiation and home grown schismatics like Quakers - 'a poor deluded people' - he could be well assured here of his oft strongly stated view that, 'drunkenness is the greatest eye-sore'. On the other hand, the windmill lad delivering flour to the White Hart had stopped completely, looking on with an amused stare of firm approval as the entertainment unfolded. Elsewhere, General Monck had marched south into London the year before, setting the cogs into motion for the return of the King, the end of the Commonwealth and the coronation of Charles II in April 1661. Further afield in Europe, many eyes were focused on the threat to Christendom from the Turks. Moving once more towards Central Europe, they would be at the Gates of Vienna for the final time before the century was out. Indeed, nine years later, villagers would be 'asked' by royal brief to contribute to a fund for Christian captives of the Ottoman backed Barbary Pirates in Algiers. But back at home, Henry Bishopp was the most prominent man Henfield had seen in a century. For his support of the royalist cause, he was newly appointed by Charles to the eminent position of Postmaster General - eyes looked on across the kingdom with envy. The war and Commonwealth had brought many changes, some lasting and some very temporary. Stretham Manor, part of the Bishop of Chichester's lands in the area had been expropriated to the Roundhead Sir John Downes, MP for Arundel, although tenants like Thomas Bellingham at Stretham farmhouse and George Rainsford at New Hall remained. On the King's return, Downes' head was soon detached, with the lands returned to the Bishop - and so to Henry Bishopp, whose family had held it on long term lease since his grandfather's time a century earlier. However, Henfield's Medieval deer park north of the village had fallen into permanent ruin after the Civil War - like many countrywide. With protection and funding removed, the park pales had been taken by locals for building materials, the deer eloped and the two ponds destocked. But, aside from the keepers, it can be guessed that most villagers cared little for the loss of this elite preserve. On the High Street, the drunken spectacle over, the maid approached a doorway and entered the establishment of Elizabeth Trunnell to a "Good day and welcome Miss!" Requesting the items needed, she reached into her apron, pulling out a copper farthing - or was it? Yes - but this was no general legal tender. While professionally minted, it served duty only in this shop. But Mrs. Trunnell would supply all that she needed today. In fact, in 1668, a newly minted local ha'penny would enter the financial fray - nearby shoemaker Thomas Pilfold likewise recognised the power of tokens and got in on the act. The Royal Mint was producing insufficient small change for the poor, so the tokens were officially tolerated. Eleven years later Charles II finally outlawed them, minting large numbers of his own ha'pennies and farthings in their stead.

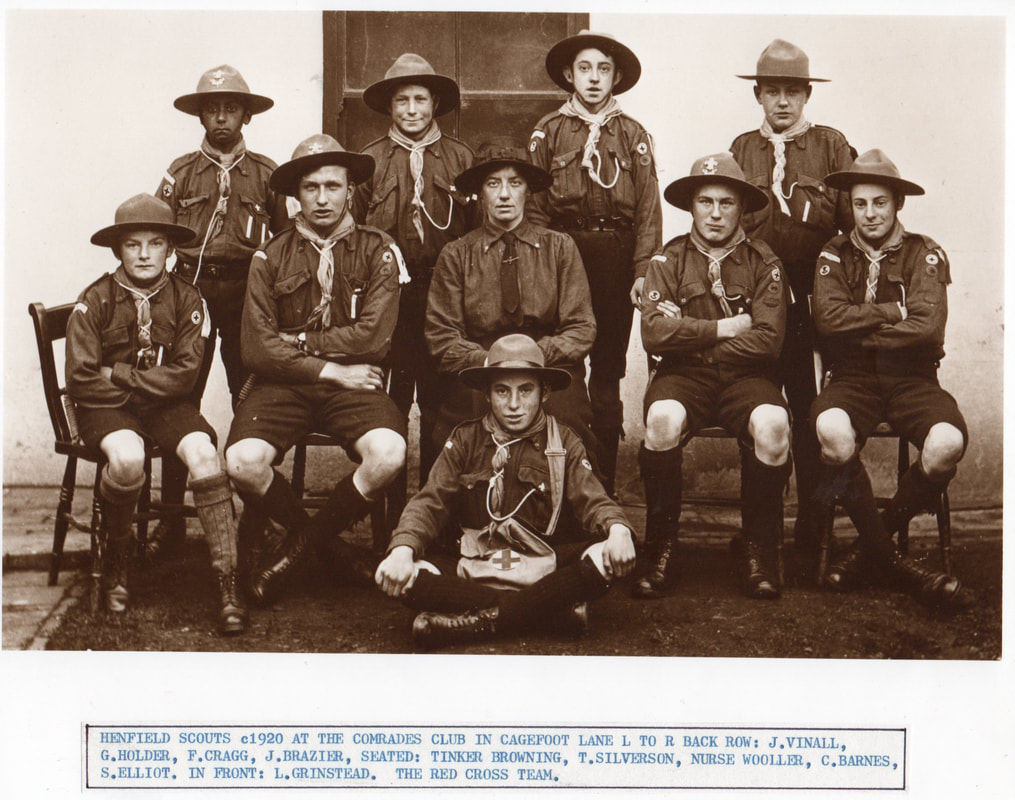

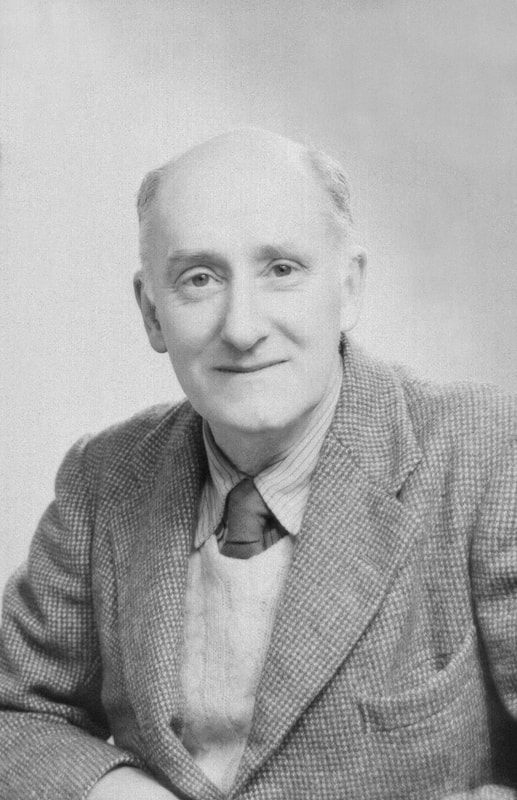

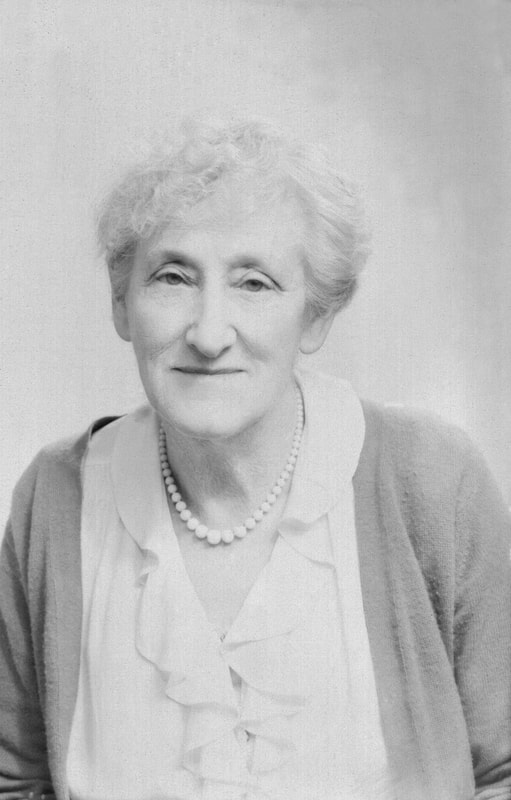

These two trade tokens, donated by the Friends of Henfield Museum, can be seen in the museum's new medals, tokens and coins display - drop by and spot them! By R. S. Gordon. Article first published in BN5 Magazine, September 2021. More of the choice words of Henfield's Revd Richard Allen can be found in his three pamphlets, available courtesy of the Bodleian Library. To read further into both the Trunnell and Pilfold (sometimes spelled 'ford') families and the social and numismatic background of the tokens, see Geoffrey Barber's 2023 article published on this blog. James William Vinall was born and lived his entire life in Henfield in the early 20th century. His paternal grandfather was reputed to be of South Asian descent, and he was known for having a distinctly Asian appearance, not something common in Henfield at the time and an early example of diversity in the village. He was very much part of the Henfield community, but his life was tragically cut short in 1945 due to extraordinary and harrowing events that took place while he served with the RAF in World War II. James’s early life and contribution to the community James (who more commonly went by the name Jim or Jimmy) was born on the 30 June, 1904. His parents, James Sr. and Fanny Vinall nee Browning, were also from Henfield. His South Asian ancestry is said to have come via his paternal grandmother, Jane Vinall, also originally from Henfield, who conceived his father while unmarried and working as a seamstress in France. Jim’s extended family owned the successful Henfield Vinall's Builders business and he and his father worked as builders for the company. He was very much involved with the Henfield community throughout his life. He played for the Henfield Cricket club from 1921 to 1939 and was also club secretary before the war. He played for the Henfield Football club and is seen in the photo below in the 1936/37 season, also being pictured with the Henfield Boy Scouts Troop c. 1914. At the Henfield Museum on the rear wall, you can spot him in the large photograph of the High Street (c. 1911), riding his bike as a child. He married Laurie Evelyn Vinall (née Lunnon) of Rottingdean. The ill-fated flight mission During World War II he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve, serving as Flight Engineer - despite being over the age where he would normally have had to serve on active combat missions. On the 14 March 1945, he and a crew of airmen were part of a specialised B-17 radar jamming squadron supporting a bombing attack on the German oil plant at Lutzkendorf (now part of the town of Braunsbedra). Their plane was hit by German flak and the engine caught fire. It seemed that the plane was going to crash so the pilot ordered his crew to parachute out. The pilot went to follow them but was caught up in oxygen tubing so was delayed. By the time he disentangled himself he was too low to safely bail out. However, the fire had extinguished itself and remarkably he was able to fly back to England safely, albeit without the others in the crew, including James, who had already bailed out - likely somewhat of a father figure to the crew at the age of 40, he had been the last to leave after checking that the rest had got out. Jim and the crew landed safely near the French border but were captured soon after by the Germans. Two members of the crew were separated and moved to a POW camp, but James and the remaining airmen were taken to a prison in Pforzheim, a region that had recently been heavily bombed. On their way there, they stopped at a village called Huchenfeld where they were to be held for the night in the boiler room of a school. As the region had recently been bombed and suffered heavy casualties and destruction, the population were no doubt very angry. An SA officer at a nearby village, Dillstein, heard the airmen were close and rallied the Hitler youth of the region to confront them. Jim and the crew were forced out of the boiler room and confronted by an angry crowd. Fearing for their lives, some of the crewmen tried to escape, causing a commotion. In the chaos, James and several others were able to escape, each in different directions. Sadly, though, four of the men were quickly rounded up and shot in the nearby cemetery. Jim was captured the next day and was briefly held in a police station in Dillstein, before being taken outside where he was beaten with a heavy stick until he collapsed. At this point a 15-year-old Hitler Youth member who had apparently lost his mother and five siblings in the bombing shot him dead. The other escaped men were also eventually recaptured but were held as POWs before being released at the end of the war. The case was tried by a war crimes tribunal after the war. The youths who shot the crewmen were given 15-year or 12-year jail sentences. But it was determined the Nazi officers and local officials who had instigated the killing and provided weapons were guilty to a more severe degree and three were hanged for their crimes.  James (far right) with the crew who would later take to the air in the B-17 Flying Fortress 'HB779 BU-K' at Blickling Hall, winter 1944-5. Photo by Dudley Heal (standing next to James): c/o 214 Squadron Association Reconciliation 47 years later, in 1992, the priest and several congregation members of the church in Huchenfeld, the German village where four of the men were killed, were so stirred by the terrible events that had happened, that they organised for a plaque to be mounted in the village church, memorialising the murdered crewmen. The widow of one of the crewmen who had been shot was present for a special church service. She had come in reconciliation and wanted to offer her forgiveness. During the service it is said that an older gentleman, full of sorrow, discreetly confessed to one of the clergy that he had been one of the young men who had shot at the crew. He then quietly slipped away from the service. The pilot of the ill-fated flight, who had survived by being able to fly back to Britain, was still alive and well at the time. However, he had not heard about the fate of his crewmen until he came across the story of the memorial. He was so moved that he commissioned a local artist from where he lived in Wales to create a rocking horse - 'Hoffnung' (Hope) which he gave to the children of the German village’s Kindergarten. The bond between the airmen’s families and the village community continued to flourish. In 2003, James's grandson was christened in Huchenfeld. In 2008 the pilot’s home village in Wales was twinned with the German village. It was another moving act of forgiveness, proving that reconciliation and hope are possible, even in the face of such terrible events as those that happened to Jim.  'Hoffnung' the rocking horse with German schoolchildren on his 25th birthday. Photo: Cambrian News, 18th Sept 2019 Conclusion The events that took place in March of 1945 led to a harrowing and tragic end for a remarkable man who held a central part of the Henfield community in the early 20th century. Nevertheless, forgiveness and hope did eventually prevail. When you next visit Henfield Museum, have a look on the mural for the little boy on the bike and you will know his story. Allison Dinnis, 2022 Many thanks to Adrian Vieler for sharing his research with me and to Alan Barwick of the Henfield Museum for bringing James Vinall’s story to my attention and helping me to find further information available at the museum. A version of this article was also simultaneously published in the November 2022 edition of BN5 Magazine. Key Sources - Peter Walker, ‘Hoffnung’ (Hope) - the rocking horse and the reconciliation between Llanbedr and Huchenfeld - the background story of friendship between former enemies', 214 (FMS) Squadron Association (2003) - Oliver Clutton-Brock, 'Footprints on the Sands of Time', Grub Street Publishing (2003) - Trevor Grove, 'Murdered by the Mob', Daily Mail (Saturday 21 December 2002) - The Henfield Museum Collection. For further information on James's story and that of the rest of his crew, see also the 214 Squadron Association website, searching the page for 'Vinall' or 'Flying Fortress Mark III HB779 BU-K' and the aircraft page on the Aircrew Remembered website. John Cameron Andrieu Bingham Michael Morton, better known as J. B. Morton and, to his friends, as Johnny Morton, was born in Tooting, south London on 7th June 1893. He was an English humorous writer noted for authoring a column called "By the Way" under the pen name 'Beachcomber' in the Daily Express from 1924 to 1975. His father, Edward Morton, began his career as a journalist in Paris and introduced his son to two of his greatest loves, France and wine. As an only child, at the age of eight, JB went to Park House prep school in Southborough, Tunbridge Wells and in 1907 to Harrow School, where he did not distinguish himself. Failing to win a scholarship to Oxford he gained entrance to Worcester College, changing schools three times and leaving after one year. His first job was writing revue material in the Charing Cross Road for a minor publication and in 1914 enlisted in the University and Public Schools Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers, as a private, being sent to the trenches in 1915. In 1916 the battalion was disbanded and JB who had fought at Cambrai and Vermelles was commissioned with the Suffolk Regiment, serving on the Somme, entering hospital in Etaples with shellshock. Pronounced unfit for active service, he spent the rest of the war in the Intelligence Service, branch M.I.(7B). At the end of the war in 1918, he joined the staff of the Sunday Express, where he wrote mainly about country walks with a selection of jokes, poems and fairy tales. Three years later, he moved to the Daily Express as a feature reporter, taking over the ‘Beachcomber’ column from D.B. Wyndham-Lewis in 1924. By 1922 he had joined the Catholic faith, becoming a friend of Hilaire Belloc and his son Peter, who were living in Shipley near West Grinstead. He bought a cottage in Rodmell near Lewes, whose best-known inhabitant was Virginia Wolff and nearby at Charleston, Firle, the Bloomsbury set. As a keen walker of the South Downs, he walked in several foreign countries including the Pyrenees, Italy, Poland, Ireland and Norway. By 1926 he was sharing a room with Peter Belloc in Ebury Strett, London and on the 24th September 1927 married Mary Annunciata O’Leary. She was born on 15th March 1897 in Cappoquin, County Waterford and had qualified as a medical doctor. Little is recorded of their life at this time, possibly in London, until in 1939, they appear in the Register living at Potwell in Cagefoot Lane, Henfield. During this time, while still employed by the Daily Express, Morton published a number of books: It is reported that to escape the Labour government of the late 1940s they moved to Dublin for two years and subsequently to 16 Sea Lane in Ferring near Worthing, where they were happy until Mary’s death on 12th January 1974. After her death, Morton stopped writing his column, lived on a diet of bread and jam (he had never learned how to cook) and wandered around the house looking for her, not realising that she had died. He subsequently entered a nursing home in the area and died there on 10th May 1979 aged 85 years. J. B. Morton is buried in Windlesham, Surrey. Article by A. Vieler, 2021. Acknowledgements

The information in this article has been taken from various sources including ‘Beachcomber, The Works of J.B Morton’ by Richard Ingrams. The photographs of John and Mary are taken from the Marjorie Baker Collection at Henfield Museum. This tale begins with tumultuous days in early 19th century Brighton, but the Hall family played a notable role in Henfield's history for well over half a century. Working with and marrying into the Borrer family, Eardley Nicholas Hall took over Barrow Hill house after botanist William Borrer's death. Eardley was born in 1803, and like his father, was a well-known banker and sometime wine merchant, working at the family bank of Hall, West & Borrer at 6 North Street, Brighton. Known by various partner dependent names, it was often simply known as the Brighton Union Bank. It was one of only two in Brighton to survive the 'Panic of 1825' stock market crash, to which Eardley would no doubt have lost sleep as a young banker. This 19th century version of the South Sea Bubble of the previous century was in part caused by overly speculative Latin American investment. One particularly extreme example involved the almost unbelievable story of soldier, sometime colleague of Simon Bolivar - and fraudster of massive ambition - Gregor MacGregor, who embarked on multiple society publicity tours to encourage settlement and investment in the country of 'Poyais'. Which to the horror of the settlers arriving off the wild coast of South America, turned out to be entirely mythical (an extraordinary tale well worth a read into). The crisis brought down sixty banks across the country and required the bank of England to be bailed out with gold from the Bank of France! By 1843 the Union Bank was the last one standing of seven that had opened in Brighton in the past half century and so became the primary bank of the town for the rest of the 19th century. It was eventually bought out in 1894 by what was to become Barclays. The old Lloyds branch in Henfield High Street, (formerly the Barclays site), was originally a branch of the Brighton Union Bank. On 26th March 1892, the Brighton Herald published a complimentary account by stockbroker William Baines which well captures the spirit of this era, contrasting greatly perhaps with common ideas of bankers in the 21st century! 'The house next to the Duke of Devonshire’s was occupied by Mr Thomas West, the well-known banker of The Union Bank, North Street. The Union Bank at that time was an old-fashioned round fronted building with a flight of steps leading up to it. The proprietors were Messrs Hall, West and Borrer, and with their white-haired managing clerk, old Mr. Pocock, formed a quartet of the most genial looking old gentlemen that the eye could look upon. One and all of them had something lively to say to their customers. In their general style and deportment they used to put the writer in mind of the Brothers Cheeryble*.' *Brothers Cheeryble, the kind-hearted employers of Nicholas Nickleby in Charles Dickens’s novel.' Eardley married Henfield botanist William Borrer's daughter Annette (his second cousin) in 1835 and they lived at the Hall family mansion of Portslade Place - an imposing Georgian mansion with extensive grounds built in 1795. In 1836, he was involved at the genesis of the railways, being listed as a subscriber to the Bath and Weymouth Railway Company, having bought 40 shares with a value of £2000 (and 5 more in his role as a partner at the bank). This company was soon to be bought out by the Great Western railway which moved on under Brunel to complete the line we know today. On William's death in 1862, Eardley purchased Barrow Hill from William's son Dawson - well known for his voyage to Lebanon and his return with Lebanon Cedar seeds planted at Henfield. They afterwards moved in and rented out Portslade Place, which survived until 1936, by then long out of place amongst the envelopment of the modern town. A few years after the Hall family had moved in, Barrow Hill gained its local 'Snake House' nomenclature when a house martin nest taken over by sparrows was knocked from the eaves to disgorge a feasting snake! Eardley did his best to fill the gap William Borrer had formerly played in Henfield life, contributing time and money to the church and local education - the Eardley Hall Institute would later pay his and his son's endeavours due tribute. For his daughter Elizabeth's wedding to Henry West (of the Brighton Bank family), Henfield saw a wedding the likes of which did not come around often. Five triumphal arches of evergreens, flowers, mottos and messages to the couple and flags were erected on the route to St. Peter's, with decorations inside and the altar covered by a cloth of pink - a three week honeymoon through scenic parts of England and Wales was next. Soon afterwards, Barrow Hill was opened up to host Henfield's Horticultural and Floricultural Show, instituted some years prior and already a village highlight. Two marquees went up - the large for amateur and professional entries, the small for cottagers' entries - and the famous gardens opened to the public, including groups of the village schoolchildren. With entry at a penny and events continuing until 7PM, all could attend. Carriages arrived from many miles around. The Brighton Brass Band provided the musical accompaniment of waltzes, polkas and quadrilles. Entry highlights included an exotic looking arbutus tree (Henry Longley) and a popular five foot high flower pyramid (Charles Fowler). Eardley exhibited potted grape vines with fruit ready to eat, while Mrs. Hall showed a 50lb globe of clear honey. Other prize winning exhibits from the cottagers' marquee included further honey (James Goacher), grapes (William Blake) and fuchsia, geraniums and balsams (Charles 'Lossam' Ward), artificial flowers of turnips and carrots (Alfred Collins), seedling peaches (Richard Brownings - prize, a large reference bible) and gigantic potatoes shown by George landlord Charles Stoner. For gardens, Henry Fairs won a wheelbarrow for 'Little Betley', while runner up Henry Hills won a high grade set of tools. Of the children, 11-year-old Ann Ward won a prize box for her flower device, while 13 year old James Foreman won a prized cricket bat for his wild flowers. Henfield's reputation as a garden village was very much secure. Later in life he was Justice of the Peace and a local Magistrate. In 1882, his name was cast into bell number two of St. Peter's Church Brighton, where he was a major donor for their new ring of eight bells (the existing ring of 10 now date from 1914). Eardley died in 1887 and was buried in the family tomb at St Michael & All Angels Church, Southwick. An impressive Celtic cross also stands in his and his wife Ann's memory in the churchyard of St. Peter's, Henfield, dedicated by their children. Postscript

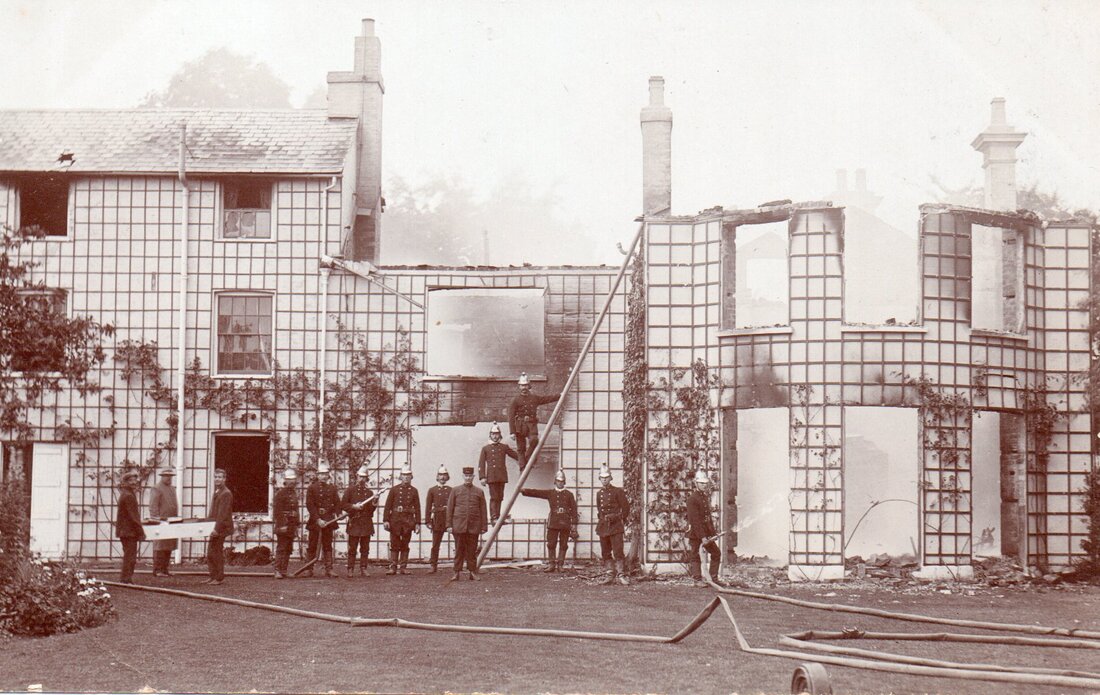

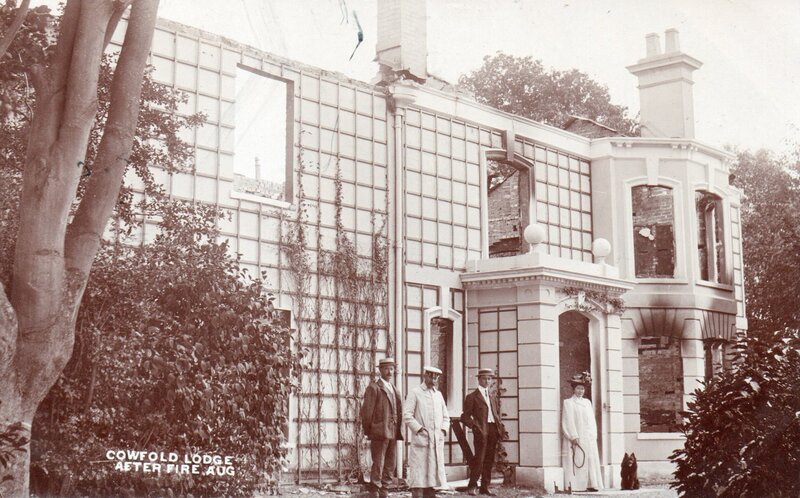

His son John Eardley Hall, also a banker, became a well known Henfield benefactor and parish councillor, after whom the local 'Eardley Hall Institute' club was named. John was a lifelong bachelor who lived at Barrow Hill with his sisters Jessie (who died in 1896) and Annette Blackburn - who had been widowed after only seven years of marriage to Frederick Blackburn. Sadly, their son also predeceased her by two years. By the night of the 1911 Census, John, Annette and Norwegian visitor Anna Bodtker - a fellow widow also resident for the 1901 Census - remained, along with their five resident servants. Having long since retired from the bank to focus on local projects, John Eardley Hall died in 1915 aged 73. By then a widow for 58 years, Annette, the last Borrer link, died in 1921 aged 84, in the house built for her grandfather William's marriage 110 years earlier. Her passing was noted in the January 1921 Parish Magazine, her continuance of the family tradition highlighted. 'The discovery of a rare flower, or one that had reappeared in its old haunt, interested her extremely. She knew all the bird notes, and watched eagerly every spring for the return of her feathered favourites, and often the news of the arrival of the chiff-chaff, wryneck or blackcap came from Barrow Hill.' The house was bought by local shopkeeper and businessman Charlie Tobitt and lay empty until occupied by the Canadian military during the war. Further damaged by this experience, the land was sold after Tobitt's death in 1953 and the house, for years home to only wildlife and the more adventurous local children, was demolished a few years prior to the development of the current Mill Drive estate in the late 1950s. By Robert S. Gordon, 2020. An abridged version of this article was first published in the Henfield Parish Magazine, July 2020. Special thanks go to E. J. Colgate for the detailed descriptions of the wedding of Elizabeth Hall and Henry West as included in his book, Henfield’s 19th Century Egg Basket. References Anon., A history of banks in Brighton (1990) Anon., The Bankers' Magazine, and Journal of the Money Market, Volume 4 (London, Groombridge & Sons, 1846) Anon., 'New Ring of Eight Bells at St. Peter’s, Brighton', Church Bells (July 1st 1882) Anon., Reports from Committees, Volume 18, Part 2, Railway Subscription Lists, 4-7, Bath and Weymouth Railway Subscription List (London, House of Commons, 1837) Baines, William, 'A quartet of genial old gentlemen', The Brighton Herald (26th March 1892) Census Records Colgate, Edward J., Henfield's 19th Century Egg Basket (2020) Middleton, Judy, Portslade House 1795-1936 (2020) Henfield Museum Records (unpublished) 1935. Captain Allan Baxter of the Henfield Fire Brigade had just welcomed his newest recruit. George 'Joe' Gillett was now outside the station, being shown around the gleaming 1915 Dennis motor engine that had replaced the old horse drawn appliance the previous year. Joe had just been kitted out in the same kind of gear he himself had started in when Victoria still had many years left to reign - gleaming buttoned heavy wool tunic and trousers, brass helmet, high leather boots and soft cap. He had no doubt that Joe'd do fine - he was a former Scout! His mind wandered to a time when the Scouts were new... August, 1908. Sitting down to breakfast with his wife Ada, he jumped up as a loud rap came at the door - a brass plate indicated the member of the Henfield Fire Brigade within. The call boy shouted "A fire at Cowfold!". Once a grocer and with years of experience in the Dorking Brigade, the chance to lead the Henfield counterpart had arisen with its formation by the Parish Council in 1904. Within five minutes he was to be found, helmet gleaming, at the fire station (now H. J. Burt's), where the bell was being rung hard. The two horses had already been brought round and hitched to the Merryweather engine. A voluntary brigade, as today, all members' jobs and homes had to be within running/cycling distance of the station. There was the last man, running up the High Street. Up, onto the engine, a flick of the whip and the brigade were off at rather stately, but determined pace. Amid shouts of "Make way!", holding tightly, they galloped down the High Street, past the startled pony and trap of one Miss Brown, headed to the station with Henfield violets aplenty. It would be no mere stack fire, but their first major event, at Cowfold Lodge. The moment would be photographed for posterity, quite probably by the brigade member Edwin L. Merrett. Henfield's postmaster and chemist, he also produced postcards to sell in the shop, including of this very event. The Cowfold Lodge Fire of 1908 - description from a local newspaper The fire at Cowfold Lodge on the 6th August 1908 was the first major fire attended by the Henfield Fire Brigade. The house, situated on the eastside of the A281 on the southern edge of the village, was owned by Arthur Labouchere who lived there with four servants. It was around 1 a.m. that a gas explosion was heard in the front hall, and within fifteen minutes flames had reached the roof and the whole front of the building. Mr. Labouchere roused three of the servants who escaped from the house unharmed in night attire and coats, but Lilla Clark a 27 year old housemaid in a back upper bedroom was not so lucky as her escape route had been cut off by the fire. She cried out that she was on fire, when in fact she wasn’t, and a fellow servant Miss Cooper on hearing her, believing this to be true, shouted to her to jump. She fell 20 feet to the ground and received serious injuries to her spine. If she had waited a few minutes a ladder was being brought around by which she could have escaped without harm. Mr. Labouchere, who had lost his moustache and much of the hair on his head in the fire, roused his neighbours and sent messengers to Henfield and Horsham to raise the fire brigades. The Henfield brigade led by Captain Allan Baxter with second officer Walter Powell, ten firemen, and a callboy, were first on the scene at 1.50a.m. by which time the house was completely gutted. With the exception of saving the stabling from catching fire the only other thing to do was to water down the burning timbers. The Horsham manual and “steamer” appliances arrived later, and both brigades were kept busy until well after daybreak. The building had to be rebuilt, but fortunately it was insured to the value of £12,000. Back to 1935. Four years later, the brigade's ornamental helmets and regular duties would be swapped for steel 'Tommy' helmets and wartime exercises as the threat became reality. The 74 year old Captain Baxter would take a well earned retirement in 1940 as the emergency duties became more onerous. After service in the RAF, Joe Gillett worked as a coal man, living with his wife Ciss at Wantley and continuing in the brigade until 1967. Having served 17 years as station officer, he retired in the era of electric sirens rather than that of bells and messengers related by colleagues in his early career. Joe was a well known figure and Parish Councillor who some readers may remember - in fact, on 8th February 1994, he opened the very museum building his helmet now shines brightly in!

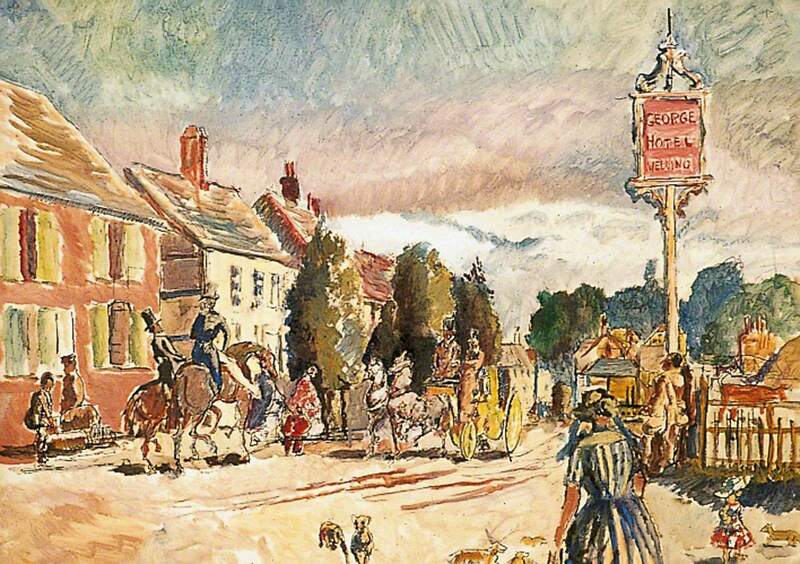

By Robert S. Gordon. An earlier version of this article was first published in BN5 Magazine, July 2021 Malcolm and his sister Hilda Lucy Milne (1874-1959) were born in Cheadle, Cheshire and were children of Lucy Midwood (1847-1899) and John Dewhurst Milne (1847-1899). Malcolm was born on the 14th October 1887 and attended Sedbergh School from 1900 to 1906, and was articled to a firm of Manchester architects, Thomas Worthington & Sons, but ill health prevented him following that career. He turned to art, and between 1908 and 1911 studied at the Slade School of Fine Art under Professor Henry Tonks, and the Westminster School of Art in London under Walter Richard Sickert. During WW1 he enlisted in 1914, but no doubt due to his ill heath served with the First British Ambulance Unit in Italy, and produced drawings of Dolegnano and Udine while there. In the early 1920s he was painting in Italy, Sicily, and travelled quite extensively in Europe and the Middle East throughout his life going to such places as Egypt, Syria and Turkey. In 1926 Malcolm and his sister Hilda came to Henfield and stayed with their relative Miss Winnifred Shaw Harrison at ‘Dykes’, a cottage on the north side of Henfield Common. Malcolm had his studio in a wooden hut in the garden just to the east of ‘Dykes’. In 1927 a house was built on the site which was named ‘Dykes Studio’; it is now called ‘Camellias’. It was here that he lived with Dr Walter Archibald Probert (1867-1946) a retired physician, and had his studio. In 1928 Malcolm was elected a member of the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts where he showed his work until 1952. Hilda lived with Miss Harrison at ‘Dykes’, and had her studio in a building at the bottom of the garden bordering on Henfield Common. This building can still be seen in ruinous state when walking along the top of the Common - in a former life it had been the cottage 'Dogham Place', once subdivided into two tiny households in the Victorian era. When Miss Harrison died in 1939 she left ‘Dykes’ to Hilda. Malcolm was the more recognised of the two artists. He specialised in flowers, for which he is noted, but also painted landscapes, portraits, and did pen and ink drawings. A collection of 31 of his paintings and drawings were exhibited at Arthur Tooth & Sons 155, New Bond Street, London from October 21st to November 7th 1931. He converted to Roman Catholicism in 1943 and died at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford on the 19th August 1954. Hilda died on the 15th September 1959 at Henfield. Both are buried in Henfield Cemetery. The Tate Gallery, British Museum, and the V & A hold examples of Malcolm's work. In 1966 the Ashmolean Museum put on a retrospective exhibition of 91 of his paintings and drawings, and in 1969 an exhibition of 69 pieces of his work was put on at the Worthing Art Gallery. The paintings in Henfield Museum (seen below) were done to form part of the 1951 Festival of Britain exhibition staged in the school on Henfield Common. He also painted the scenery for some of the productions put on by The Henfield Players. by Alan Barwick, Curator For more on Hilda, see the 2022 article by Rebecca Welshman within her project, Violet and Crimson: Radical Women in the Sussex Countryside (1900-1951). Paintings for the 1951 Festival of Britain: Malcolm Midwood Milne

A Little Known Sussex Memorial: the Great War Propeller Cross at St Peter's Church, Twineham19/12/2020

St Peter's Church at Twineham is a rare early 16th century brick structure with Horsham slab roof and broached shingled spire. As you walk into the porch, glance to your left and you may notice something that looks a little out of place.

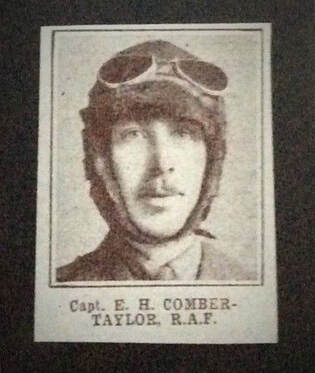

Within lies a sombre reminder of the aerial battlefields of WW1 - a temporary grave cross made from the propeller of an aircraft, brought over from Esquelbecq Military Cemetery in France. It memorialises Captain Eric Horace Comber-Taylor, K.I.A. on the 16th of June 1918, at the age of 29.

Born in June 1889, the son of Mr. William Overton Comber-Taylor and Mrs. Ida E. Comber-Taylor of "Furzelands" in Albourne (since renamed "Firslands"), Eric attended St. John's College (now Hurstpierpoint College). After school he became a bank clerk for the National Provincial Bank at Folkestone, moving to 33 Alexandra Street and later moving on to the Hythe branch.

Volunteering in Brighton in September 1914, soon after the outbreak of war, he began as a Private in the Royal Fusiliers, heading to the Western Front over a year later in November 1915. Returning for officer training in March 1916, he began his journey to becoming a pilot of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), being commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant in August 1916. Switching into the RFC within a few months, he earned his aviator's certificate on 7th December of that year. 1918 found him serving in the newly formed RAF with No. 10 (Reconnaissance) Squadron on spotting and bombing duties. 10 Squadron mostly flew BE2s well suited to their recce role, but for about 4 months from June 1918, they were supplied with a small number of the Bristol F2b 'Fighter', which Comber-Taylor also flew.

Artillery observation or 'spotting' was an unexciting, but necessary job. It involved flying within a small area for extended periods, reporting back to artillery posts via radio transmitter as to the impact of their volleys until they were zeroed in on their target. While the artillerymen on the ground couldn't radio the aircraft back, they could relay simple acknowledgements or queries with fabric laid out on the ground or other visual signals. The task could be quite an arduous one for the pilot and observer, depending on the skill of the particular artillerymen they were directing. However, while it required close attention, the surrounding skies could not be neglected - repeatedly circling artillery spotting aircraft could make tempting sitting ducks for enemy pilots. On occasion, this scenario would be used by Allied pilots who would sit in the clouds above the spotting plane, awaiting the arrival of an opportunistic Fokker or Albatros to take the bait.

Aerial bombing in WW1 was of a very different nature to WW2. Although larger, specifically designed bombing aircraft had arrived by the war's end and Zeppelins made some costly sorties to bomb from the skies above Britain, most often a few bombs on underslung racks would be dropped from small aircraft like the Bristol fighter of Comber-Taylor at a relatively low height, or sometimes simply thrown from the cockpit. Although accuracy depended on the pilot having the required skill and taking the necessary risks at low height, it was a world away from the massed area bombing to come in WW2. On Sunday the 16th of June, he lined up his only recently delivered Armstrong Bristol F.2B (C967) for take off from Droglandt aerodrome. A few miles north west of Poperinghe, he and his Observer, 2nd Lt. G. A. Cameron were scheduled for an artillery observation mission. Sadly, on take off, the engine immediately failed, causing the aircraft to stall. Whether due to a mechanical issue or due to Comber-Taylor not being familiar with the performance of the type, he was killed in the ensuing crash, while Cameron survived with serious injuries. Unfortunately such events were not uncommon, although perhaps more tragic than as a result of enemy action. Returned, the wreck of C967 was struck off charge as unrepairable four days later.

Eric's father placed the battlefield cross at Twineham Church, having had it returned from France when the cemeteries were formalised with stone markers in the 1920s. Around the 2000s, it was apparently moved from its original location outside, to within the porch. The original inscription reads: 'R.I.P. CAPTAIN E. H. COMBER-TAYLOR RAF KILLED IN ACTION 16/6/18'. An inscription added to mark the return reads: 'PROPELLER CROSS FROM THE GRAVE OF HIS SON ERIC HORACE ESQUELBECQ MILITARY CEMETERY FRANCE'. The memorial may possibly be made from the propeller of Comber-Taylor's own crashed aircraft itself; however most Bristol Fighters in service had two bladed propellers rather than four. The grave is now marked within Esquelbecq Military Cemetery, Plot III, Row B, Grave 20, with the same personal inscription noted below. He is also named on the Woodmancote war memorial.

Esquelbecq Military Cemetery. Photo c/o CWGC.

At the red brick church at Twineham, a brass plaque is mounted within on the north wall, near the pulpit, and reads: 'IN MEMORY OF AN ONLY SON/ CAPTAIN ERIC HORACE COMBER-TAYLOR/ FLIGHT COMMANDER ROYAL AIR FORCE/ KILLED IN ACTION IN FRANCE JUNE 16TH 1918/ LOVED BY ALL FOR HIS GENTLENESS AND QUIET BRAVERY'.

Capt. Eric Horace Comber-Taylor. Newspaper portrait most likely from the Illustrated London News report of his death, Saturday 17 August 1918. For an additional photo of Eric, see Roll of Honour.com.

Article by R. S. Gordon, February 2017. This updated version was published December 2020. Additional background information provided c/o Adrian Vieler.

References