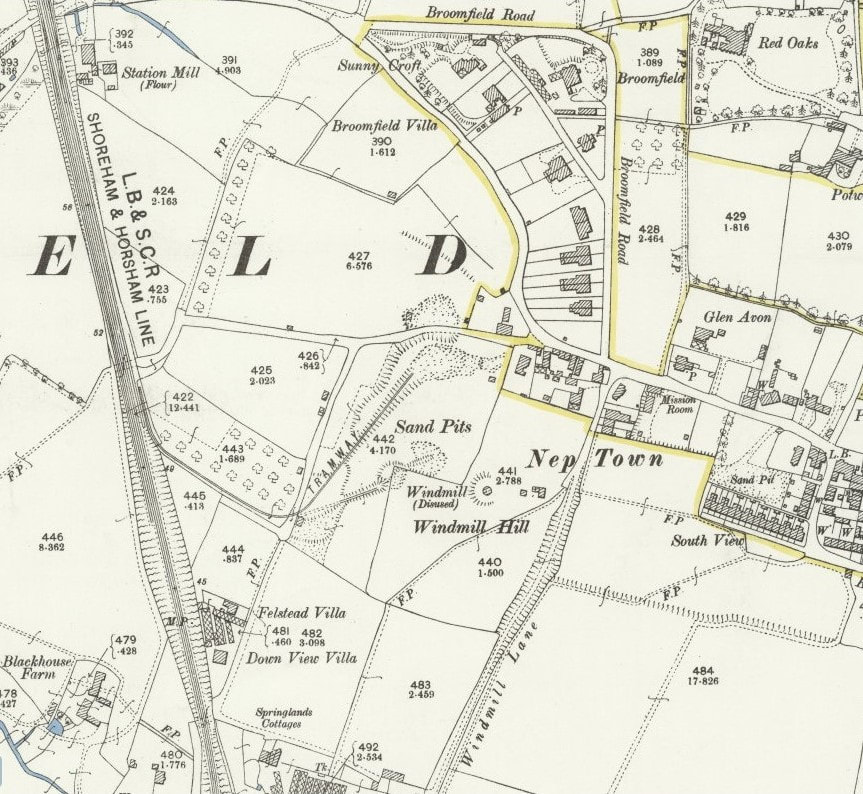

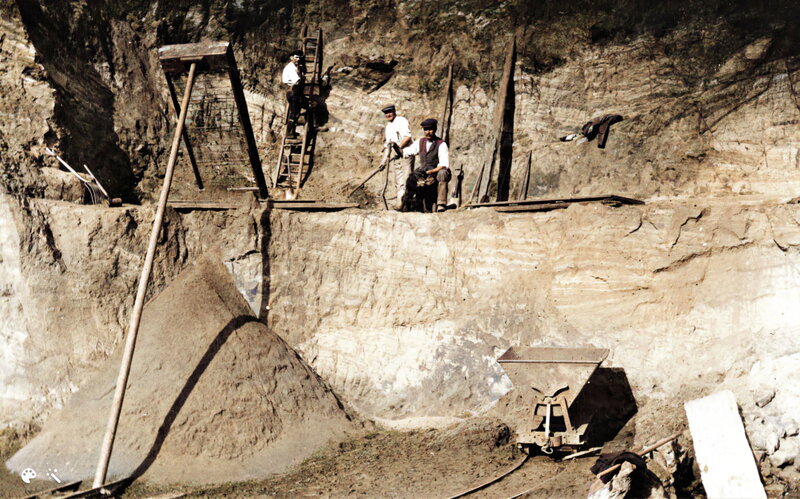

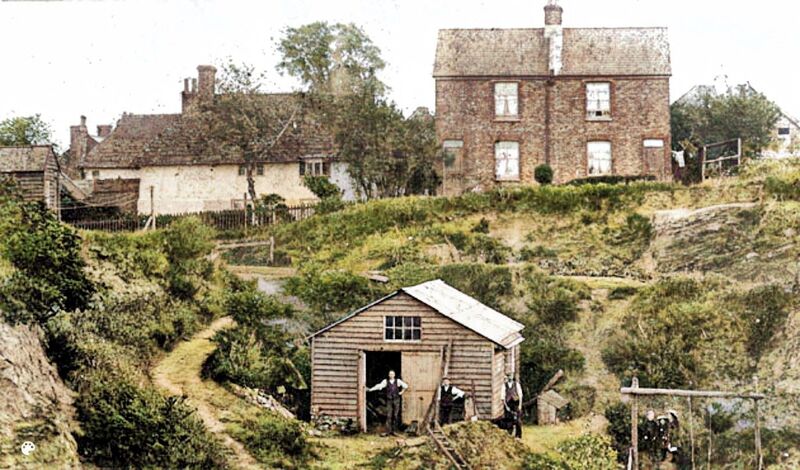

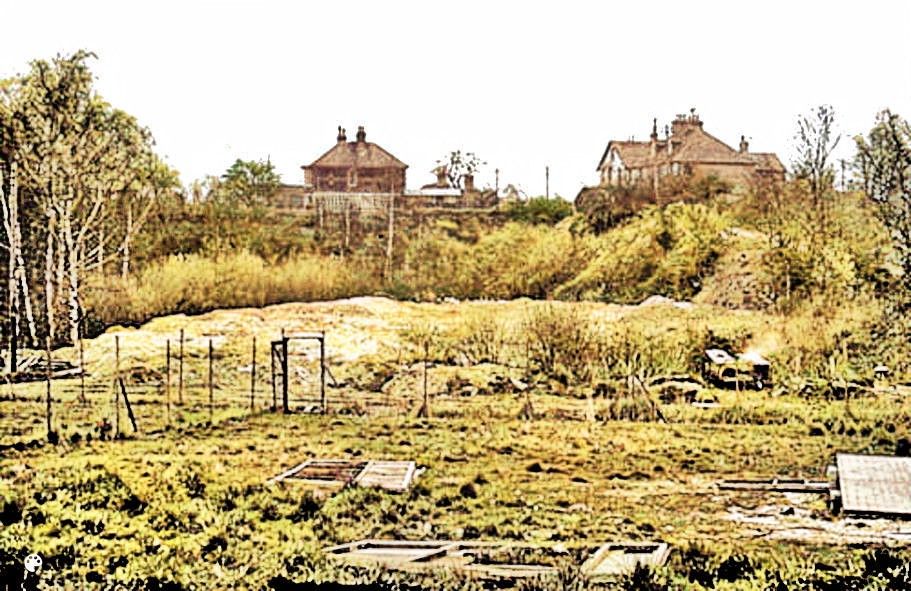

The long descending gully of the Henfield sandpit tramway, left foreman Bill Carter, right unidentified worker, c. 1912. Image: Henfield Museum (CC BY-NC-SA), colourised, 2020 As Nep Town windmill reached the end of its life with the Victorian era itself (finally collapsing in 1908), a new industry was firing and clanking up - the digging of sand. Henfield has had several sandpits over its existence, earlier pits being for limited local supply. The Sandy Lane pit was the most prominent, ultimately supplying large quantities of sand to the Brighton Corporation in the 20th century, playing an important role in Brighton's development. Windmill Hill was always a tempting place to dig, being itself a massive sandstone buttress on the edge of Henfield's sandstone ridge. Descend Sandy Lane and you will rapidly leave Henfield's sandstone, hitting the low lying brooks and floodplains of the River Adur. With an initial smaller excavation to the west of Sandy Lane in use by at least the 1870s under local builder Philip Hedgcock, by the 1890s, activity had greatly expanded to the east of Sandy Lane, with a pulley driven tramway having been put in place. With sand dug out by hand from the faces, it was first loaded into barrows which were dumped into the tramcars. Next sent on its way downhill via a long gully, it crossed the left hand fork of Sandy Lane heading on down to the London - Brighton railway line where an agreement for use of a siding was in place with the London, Brighton & South Coast railway. There a raised wooden platform allowed the tramcars to tip their load straight into railway trucks waiting on the siding. From whence it would be sent onwards, primarily for use in cement. For many years the foreman was William (Bill) Carter, born in 1867. He had moved up from Brighton in around 1900 and lived at Old Mill Cottage with his wife Alice, born at Henfield in 1863 and perhaps happy to return home. With the mill having fallen silent, its Horsham stone roofed house (now Grade II listed Old Mill House) still provided a heart to the activity in the area, with it and the neighbouring new cottages for the workers overlooking a large new pit next door! By 1901 Bill and Alice had two daughters; Nellie aged 5 and Ethel Rose aged 1 (two others had died in infancy). By 1911, Alice did not show on the Census and Nellie was a nurse of 15, with Ethel at school. Prior to moving to Henfield, Bill had been a stationary engine driver in Brighton, which would no doubt have made the construction and operation of the quarry tramway simple enough. He is shown on site in the photos below with two workers - their identities currently unknown - alongside family members. Philip Hedgcock died in November 1903, but in the preceding few years he had worked out an agreement with what was likely to have already been one of his main customers, the Brighton Corporation (forerunner of the council). The Brighton Borough Surveyor and the solicitors acting as Trustees to Philip's will had agreed that the sandpit, equipment and associated agreement with the railway would go on long term (35 year) lease to them at £600. As well as any profit going to the Trustees, a sixpence royalty per cubic yard of sand extracted would also be charged until the Corporation paid the sum off and took full ownership! From New Year's Eve 1905, the lease on the 'Mill House Sand Pit' became active. Having previously been the customer, the Corporation was now its own manager and supplier, with much of the sand going straight towards the 20th century expansion of the city of Brighton. By 1909, the pits, along with the tramway, had expanded towards Windmill Lane where the windmill's long overwatch of the Downs had recently ended. Occasionally, if Bill or another of the labourers were watching carefully enough, the pit would reveal secrets of the area's past. Truly ancient pygmy flints from the Mesolithic era saw the light, painting pictures of long ago groups of hunter gatherers congregating on this high point knapping their tools, surrounded by the untamed wild. This many millennia before the idea of nations, settled villages or arguably even the idea of the individual as we know it had arisen. Evidence of later activity came too - Roman pot, perhaps last used by an inhabitant of the province of Britannia, surveying the tamer lands of the coastal strip from what would many centuries later, become Windmill Hill. At their back, the vast Forest of Anderida stretched from the edge of whatever name the limited settlement where Henfield now stands once had, almost to the capital at Londinium. By the arrival of the 1930s, the pit was largely worked out. The last act came just before the Second World War when the field east of Windmill Lane was mechanically excavated from 1935-8, leaving a large pit and steep drops on both sides of the old, already sunken Windmill Lane. The north part of this new pit was then initially rented by the aptly named Greenfields for market gardening, with the south rented by David Stephens who ran a sawmill there. The pit is well evident today and now home to the house 'Sandpits'. An afterlife for the old hand worked pits came in the form of allotments to the south and a chicken farm to the west of the site, active until the removal of the railway in the 1960s - the foundations of the chicken huts are still well evident today. In recent decades, the former pit has returned to nature. With woodland having grown up across the site - the clamour of industry once having arisen, has now receded. R. S. Gordon, 2020 References - Barwick, A. & Carreck, M, Henfield: A Sussex Village (Chichester, Phillimore, 2002) - c. 1912 photo series (held by Henfield Museum) - Census returns - Old Mill House investiture, 1907 (privately held) - Oral recollections - Historic Ordnance Survey maps c/o the National Library of Scotland. - West Sussex Historic Environment Records: MWS3343 & MWS878 Gallery - Henfield SandpitAlong with the leading image above, these photos have been suggestively colourised and in some cases enhanced, as indicated by the bottom left corner graphics. The first set of five photos was taken c. 1912 and were donated to the museum by a grandson of Bill Carter (licensed under CC BY-NC-SA).

2 Comments

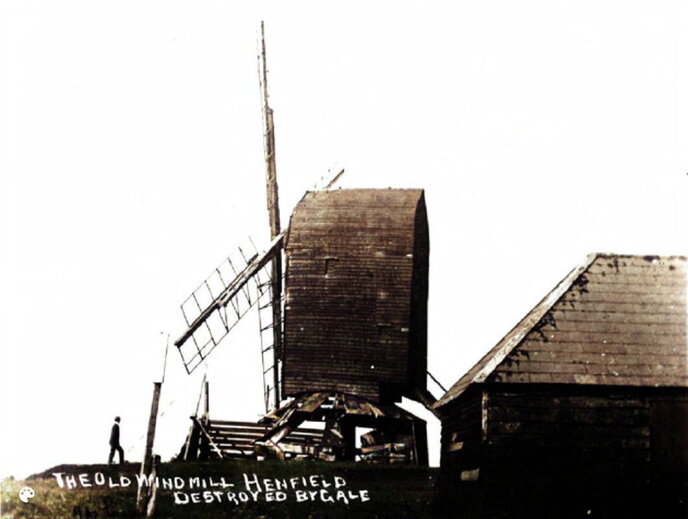

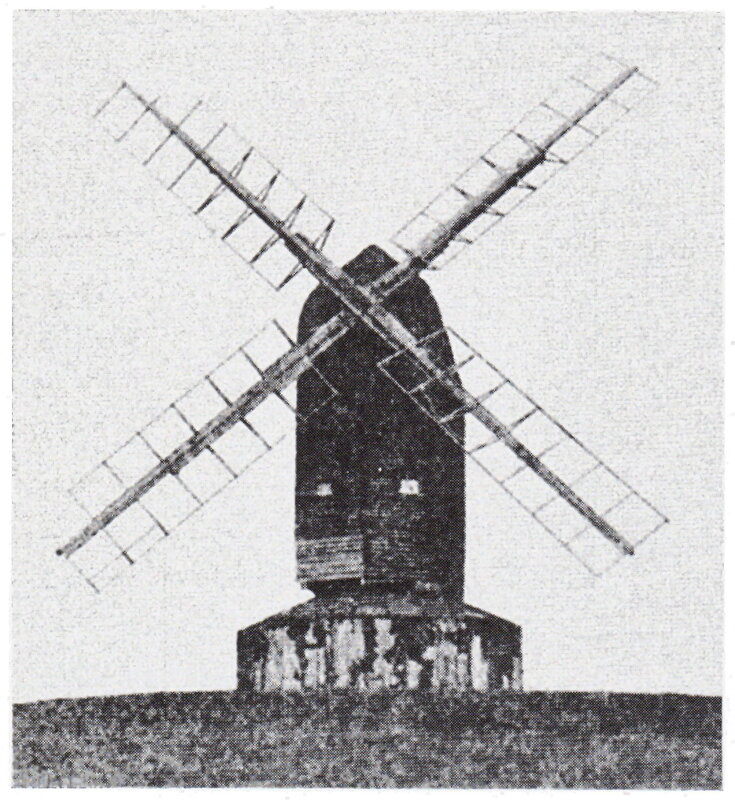

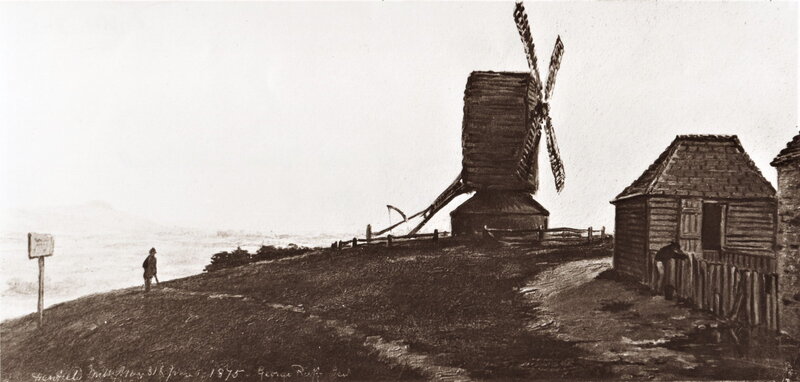

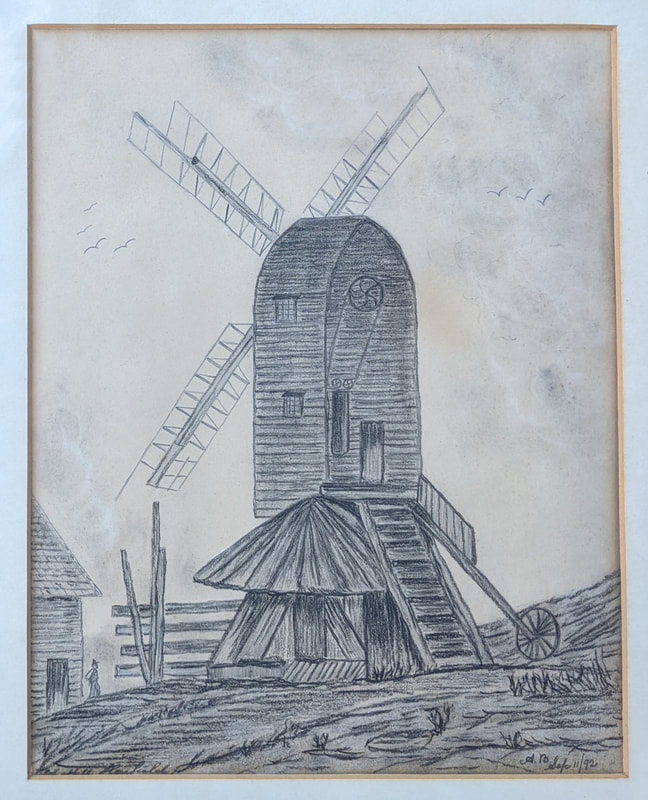

At the far end of the former hamlet of Nep Town, the sandstone ridge of the village descends to the River Adur flood plains below. Passing Mill End and Windmill Hill, the road curves down into Dropping Holms to the right and descends the ancient sunken lane of Sandy Lane at left. Over the centuries the area has been central to parts of Henfield's history - here we tell the story of what was once popularly known as Henfield Mill...  The Nep Town Mill, Henfield, c. 1890s. The barn was actually some distance closer to Windmill Lane and the photographer than it appears. Image: Henfield Museum (CC BY-NC-SA), colourised, 2020 This post mill was most likely first erected at some point in the 17th century - it probably takes a position as the second oldest of the Henfield windmills with another noted as existing in a field near the house 'Cannons' by 1575. Several 17th century sources refer to what is most likely to have been the mill on this prominent site, although it is not known when the Cannons mill ceased operating. For example, the Commonwealth Survey of 1647 refers to notable local landowner John Gratwicke of Shermanbury holding 'the Windmill house and lands'. The mill was definitively featured on Budgen's 1724 map of Sussex and also features on Yeakell & Gardner's 1778 map of the county, being a notable Henfield landmark for generations. But this was only a continuation of use of an ancient site, with finds of Mesolithic pygmy flints having shown that hunter gatherers once lived and worked at this high vantage point. It was commonly known as 'Henfield Mill' before the arrival of the 'New Mill' on the Common in around 1820, after which it tended to be known as the 'Old Mill' or 'Nep Town Mill'. A post mill body or 'buck' would be rotated on its post to allow its sweeps to face the prevailing wind direction - woe betide a mill facing the wrong direction in a gale! This meant that millers or assistants needed to be ready to turn the mill at a moment's notice if the wind got up from a new direction or if a storm arrived in the night. The turning pole with wheel attached at back to ease the job of rotation can be seen in the photos. Newer mills such as the Henfield Common windmill (built in 1820) were updated with fantails, which on post mills like these were attached to the ground wheel and automatically rotated the mill to face the wind direction. The veteran Nep Town miller at this time, Robert Loase, ran the mill and associated farm where his wife Mary ran the dairy. Shortly prior to the announcement of the new mill, he had recently had his worst year in a quarter century milling - so quite what came to mind when he heard the news of the upcoming competition may not bear repeating! As with many trades of the day, the fortunes of milling could turn as easily as the sails of the mill itself. Robert had willed the property to his daughter (via her husband), However, on his death in 1827, a £400 debt to local landowner (and botanist of note) William Borrer was still outstanding and Mary had no choice but to sell the dairy farm - the mill however, was kept in the family for now. A characterful c. 1865 painting (the first image in the gallery below) harks back to an earlier era in the windmill's history. By Nehemiah Vinall, it shows the mill when still active - perhaps the bearded sawyer shown was the miller of the day. It links into interesting and tragic events in the mill's history and it is suggested he painted it due to a family connection. His great great grandfather William Vinall (the Elder) had been a miller and Henfield churchwarden in the latter 18th century. His son - and Nehemiah's great grandfather William Vinall (the Younger) was also Nep Town miller. One sad and dramatic day in 1795, he was drawn into the milling machinery and killed - a stark illustration of a time when workplace safety was largely an individual responsibility. With the set price Corn Law debates of earlier in the century becoming a distant memory as free trade and large industrial interests won the day amidst the increasingly corporate and globalised industrial scene, small scale local production of the sort offered by Henfield's two windmills became less and less viable. Long time journeymen millers like James Randall originally worked at the Nep Town Mill, but switched over to the new mill on the Common as demand was squeezed. There however, his situation did not ease - he was now a widower with six children and a taste for beer. A taste which would ultimately lead to three months' hard labour at Petworth Gaol for embezzlement when it was discovered that he had only been recording some of the daily transactions in the day book, the others in his own purse alone... To make matters worse, direct local competition had arrived in the form of two steam mills in 1860 and 1874 - which would themselves succumb before long to the powerful forces of the wider economy. By 1871 master miller Richard Luff and his wife Harriett were living at the Mill House, with five children and son Richard also being noted as a miller. However, having been a steady source of flour for centuries, the windmill finally went out of use in ~1880 with either Clement Knight or John Sharp recorded as being the last miller (one perhaps gave the mill a brief resurrection). Papers of the time recorded a final drama before the end when a local lad jumped onto a sail, presumably aiming to ride it a short distance. However, his hand became caught and he was unable to dismount in time, being swept up into the air. The sails were stopped, but he fell from some height, luckily surviving, albeit with some bruising and no doubt a great deal of embarrassment. Its life of grinding corn over, the mill still provided a fine vantage point over the countryside. For Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in 1887, numerous bonfires - between 20 - 30 - were apparently spotted by those watching from its steps. The mill itself was retained as a Trinity House (and village) landmark, but according to de Candole's history of Henfield it finally collapsed with 'a loud crash in a mighty gale' on Friday, February 21st 1908. By the time of the First World War a few years later, a correspondent seeking it out reported very little remaining on site. The hill it stood on is now in many places much reduced in height having been subsequently dug out during the excavation of the Henfield sandpits, with the area now being almost entirely wooded. However, the sandpits did offer a small postscript for the mill - in the same way as the prehistoric flints, Roman pottery was discovered. Perhaps, many centuries before, it had last been used by someone standing atop what would become Windmill Hill, looking across the Roman province of Britannia. Although going out of use at about the same time, the sole survival of the c. 1820 'New Mill' on Henfield Common for an additional forty-five years led to its having become much the better known of Henfield's mills today. R. S. Gordon, 2020 References Barwick, Alan., Carreck, Marjorie, Henfield: A Sussex Village (Chichester, Phillimore, 2002) Bishop, Lucie, Henfield in the News (Henfield, Private Print, 1938) de Candole, Henry, The Story of Henfield, (Hove, Combridges, 1947) Colgate, E. J., Henfield's 19th Century Egg Basket (Winchester, George Mann, 2020) Budgen's Map of Sussex, 1724 Yeakell & Gardner's Map of Sussex, 1778 Census Returns Sussex Mills Group Henfield Museum records West Sussex Historic Environment Records: MWS3343 & MWS878 Galleries - Nep Town WindmillPhotographs The limited number of known photographs of the Nep Town Mill are shown here (along with the leading colourised version in the photo above). This contrasts with the large number of surviving photographs of the 'New Mill' on the common. (Images from the Henfield Museum collection licensed under CC BY-NC-SA). Paintings & Sketches Luckily we also have a number of paintings and sketches from various artists in our collection which help to bring the mill back to life and provide information on the historic setting.

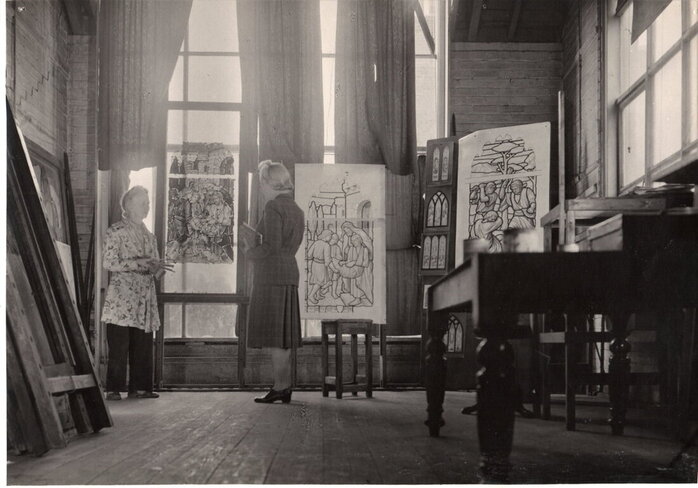

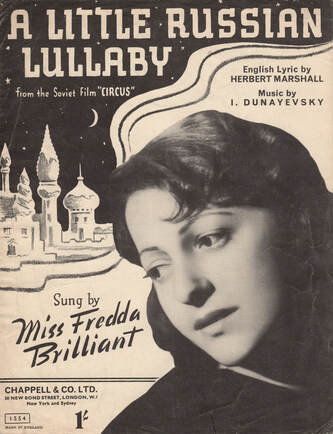

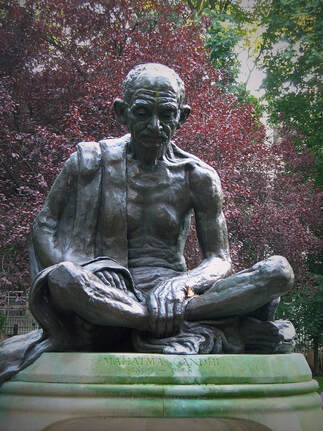

(Images from the Henfield Museum collection licensed under CC BY-NC-SA). An account by Peter Bates When we came to Henfield in 1969 the residents of Hole Farm Studio at Woodmancote were the sculptress Fredda Brilliant with her husband, film maker and translator, Herbert Marshall. Fredda sculpted many of the great figures of 20th century history, including Mahatma Gandhi and J. F. Kennedy. Her most famous statue, a 12ft bronze image of Mahatma Gandhi, stands in the centre of London's Tavistock Square. The project for the statue floundered and was saved in 1966 when the Labour Government stepped in with a grant of £4,000 towards the cost of £9,500. I remember giving them both a lift home after a jumble sale and being shown round the vast collection of small and large statues that there were in and around her studio. In the 1930s the couple lived in Moscow where Fredda, with no formal artistic training, cast in bronze many Russian film makers and authors, including Sergei Eisenstein and Anton Chekhov. She also sculpted Molotov for the Soviet Government. Fredda Brilliant, who died in 1999 aged 95 in Illinois, USA, was born into a Jewish family in Lodz, Poland. The family emigrated to Australia where Fredda became an actress and continued to act after emigrating to America in 1930. She also worked there as a scriptwriter and singer. She married Herbert Marshall in 1935 and they came to England in 1937, after their Soviet sojourn, managing to leave while the going was still somewhat good. After the war, in 1947, she played the lead opposite Michael Redgrave in Thunder Rock in London's West End, directed by her husband. From the late 1940s Fredda and Herbert spent much of their time in India where she sculpted a whole generation of Indian politicians and he made films for the Indian Government. From the mid 1960s the couple alternated between Illinois, where he was professor of Soviet Film and Literature, her London studio in Belsize Park and the converted barn studio in Woodmancote. Herbert Marshall died at Homelands Nursing Home in Cowfold in 1991. In an obituary in the Independent in June 1999, Patrick Reade writes that Fredda and Herbert returned to Sussex in 1989 and faced a bitter fight to reclaim their home from tenants and lived a very reduced state for many months. Doubtless folk will remember that 'she promenaded around the village of Henfield dressed in long black dresses, tasselled shawl about her shoulders and brilliant headscarf encircing her dark hair and small face - in winter she would wear a fur cost to the knees. With her emotions unleahed, her language let loose and her clothes trailing behind her, she became something of a local legend'. Text by Peter Bates, as first published in the Henfield Parish Magazine, 2020

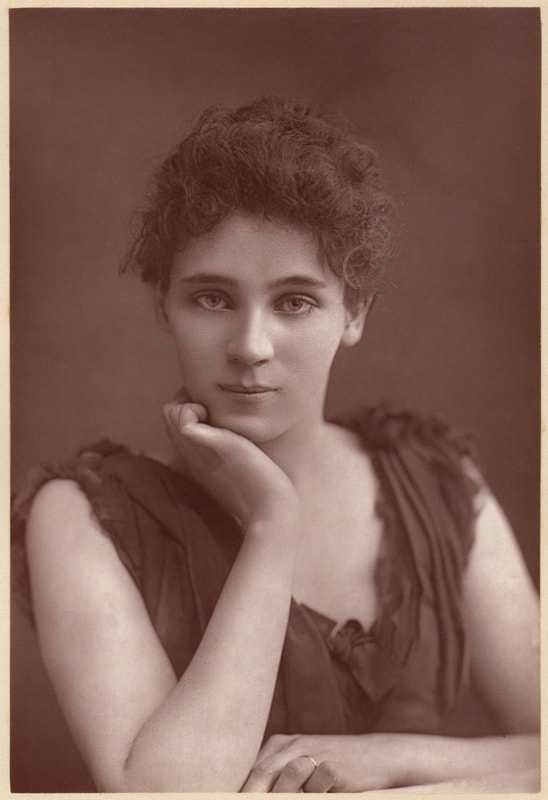

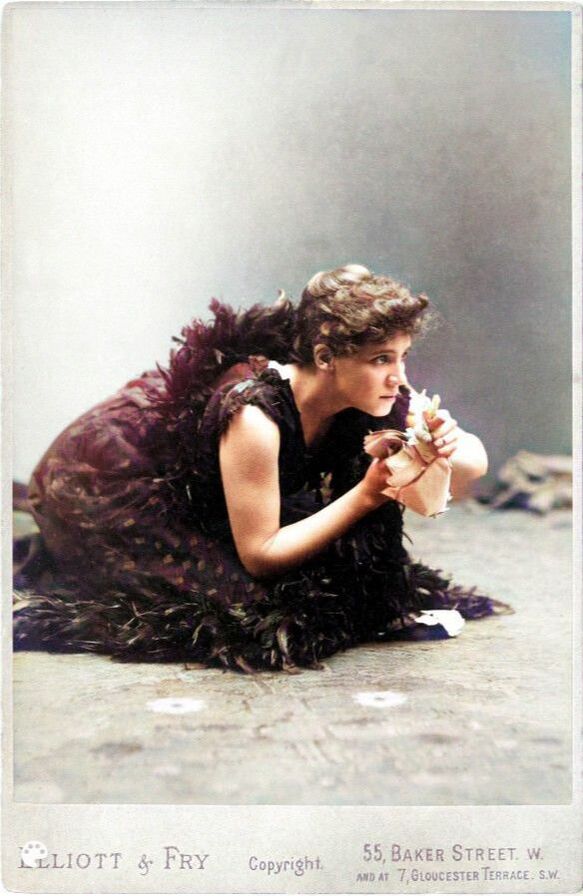

With pinned back chestnut hair and piercing blue-grey eyes, few could resist the intensity of the gaze - nor the personality to match - of Miss Elizabeth Robins. Actress, writer, suffragist and feminist, in her time a darling of the London literati, a friend of Oscar Wilde, Bernard Shaw and Henry James, she was known in this country as the 'High Priestess of Ibsen'. ~ Born in Louisville, Kentucky during a thunderstorm amidst the savage bloodletting of the American Civil War, her father moved the family to Staten Island, New York. A self made businessman and follower of the Utopian socialist policies of Robert Owen, he instilled in Elizabeth the spirit of inquiry and social and scientific scepticism. From the age of 10, 'Bessie' Robins was largely raised in Zanesville, Ohio by her grandmother Jane, a devout and forthright woman who became her 'touchstone' and strong formative influence. Her father Charles moved around frequently for work and her mother Hannah was often considered mentally unstable, spending the majority of her latter years in an asylum. This was blamed on family marriage to cousins, a hereditary weakness which the family was all too aware of. In fact, all of the Robins children avoided having children of their own as a result. Given a book of Shakespeare by Jane and inspired by seeing Hamlet aged 14, she yearned to start a career on the American stage, despite family reservations and her father initially having had a scientific career in mind for her. As a last attempt at distraction from this lure, Charles made the somewhat dramatic, but characteristic move of taking the 17 year old Elizabeth along with him during the summer to his job at a gold mining camp in the Colorado mountains - to be tutored by him and to learn more of nature. Although these skills were to come in useful later, she was not dissuaded from the theatre and a little later realised that her father did not truly have the money to send her to college anyway. Boldly, on 24th August 1881 she left for New York at the age of 19 with little of her own money and few contacts. A striking and perhaps crucial exception to this was her mother's cousin, Lloyd Tevis. The wealthy President of the Wells Fargo bank, her mother arranged a $500 loan from Tevis, who would also prove a future saving grace in an era when members of companies would have to fund such things as costume entirely themselves. Payment for acting and elocution lessons as well as direct loans to her theatrical troupe later resulted from his promise to be her 'good genie and good friend'. However, money was only one part of the equation. She met her 'first useful dramatic friend' James O'Neill, by chance, as they lived at the same boarding house. After a fruitless tour around agencies, she seized her chance to join his touring troupe. Her three line debut came on Boxing Day 1881 in the play The Two Orphans, set in Ancien Régime France. Determination and hard graft did the rest. Almost bywords for Robins - or 'Clare Raimond' as she branded herself for the character roles O'Neill cast her in. With O'Neill's company breaking up in early 1883, she joined H.M. Pitt's, choosing this moment of independence to revert to her own name - but, on the advice of her family the more seriously theatrical 'Elizabeth' rather than 'Bessie' was chosen. As the 1880s gained pace, her increasingly large roles soon began to gain attention. One typically favourable notice in the Dramatic Times of June 12th 1882 for her role as 'Rose' in Forgiven remarked that she was 'attractive in appearance, remarkably intelligent and does her work with an artistic discrimination and a natural force that promise much for the future'. Pitt was no doubt pleased, as he had given her the role as a result of a loan arrangement with Tevis. Maintaining such traits in the theatrical life of the time was no easy feat - arduous travel, little sleep, preparation for dress and role, before even reaching the 10 performances a week, usually with no understudy and a written or unspoken contract not to let the company down due to illness. In August 1883 her choice of career became more secure after she moved to the long established Boston Museum Theatre Company. Pitt had run into financial trouble and been unable to pay his players - Boston Manager R. M. Field had his eye on the talent and Tevis had negotiated a strong three year contract for Elizabeth - $25 per week, rising to $50 by the third year. This was to involve an estimated 200 smaller and larger roles in Shakespeare and modern melodrama. Her debut in front of the refined Boston audience as the heroine Adrienne in A Celebrated Case was a challenge and a considerable shift in gear. Of the many admirers who she was surprised to find now pursued her, a fellow Boston Museum actor, George Parks, had done so with such alacrity, that finally, despite initial personal and family reservations, he succeeded in convincing her to marry in January 1885 - at a secret ceremony in Salem with just one witness. But of course the news quickly got out. As a direct result, Field informed her by letter of her early release from her Boston Museum contract at the end of that season. Although Elizabeth had through half a decade of hard work gradually become quite successful, if with very little choice over roles, she suffered multiple personal and public blows as the '90s approached. In 1885, suffering from continuing fears and 'delusions' of violence towards her children, her mother had been placed into 'the living grave' of an asylum where her own Doctor later committed suicide - Elizabeth felt ongoing guilt about her inability to support her mother personally. In September of that same year, she learned at curtain down one evening that her Grandmother and in some ways the family glue Jane had died. Further, although they were not very close, in November, her sister Una also died from malaria. After leaving the Boston Museum Company she had to rejoin O'Neill's - she saw success in the prominent female role of Mercedes in his very successful productions of the Count of Monte Cristo, including in her hometown of Zanesville where she and production were given rave reviews. But as expected, she found the repetition of the role oppressive and only stayed for the autumn of 1886 - a decision hastened by the drastic setback of a boiler flood ruining all of the expensive and especially fitted theatrical gowns she had had made over the summer for the following season. While there was passion and fondness in her relationship with George, they were often apart due to the nature of the work. He had not matched her consistent success in acting, but certainly had with his insistence on marriage and his level of emotional dependency on her, which she would and could not reciprocate. He, as more of a traditionalist than most in the theatre set of the time, wished for nothing more than to have Elizabeth cease acting and be provided for by a level of success that ever eluded him. In 1886, further struggling with illness which had forced him to stand down from a role, subsequent financial distress, and a general susceptibility to serious depression, George weighed himself down with his theatrical chain mail and committed suicide by jumping into the Charles River. He left a stark and what can only have been emotionally traumatising note, stating amongst expressions of love, doubt and regret - that 'I will not stand in your light any longer.' His body remained undiscovered for almost two weeks - when it was found, the tragic case made front page news. Six pages of her diary for the period prior to discovery were torn out, with only the phrase 'usual shuddering dream' remaining as stark testament to that time. George's family blamed Elizabeth for the tragedy and at times she certainly also blamed herself. In addition, allusions and inferences from Elizabeth and several other sources suggest the possibility of an aborted pregnancy around this time, although this is never stated explicitly enough to be completely certain.  Elizabeth in an early role as 'Rose' in James Albery's play 'Forgiven', 1883, during her brief time with Pitt's company. Bernard Shaw cheekily suggested Elizabeth use this cigarette portrait photo of pre-'New Woman' Elizabeth as the frontispiece to a future memoir. Decades later, she did, in 'Both Sides of the Curtain'. Resolution enhanced by Henfield Museum, 2020 Despite this dark time, Elizabeth was nothing if not indomitable and had now built up considerable experience. Before George's death she had attempted to assist their financial situation by boldly going to meet and then gaining a contract to join the foremost American Shakespearean company of Lawrence Barrett and Edwin Booth, both former Boston company men. The latter had long since resigned himself to being equally known as the brother of the assassin of Abraham Lincoln. She had seen Booth perform in her first year in New York, describing his Iago as 'a perfect piece of unrestrained art', so it was a welcome move. They travelled 30,000 miles across the breadth of America from the east coast to the 'wild' west by train, the company as a whole staging 258 performances in 72 venues and ending on the Merchant of Venice in San Francisco. Needing to cut the size of the troupe, Elizabeth's contract was ended, after which she visited her benefactor and mother's cousin Lloyd Tevis, who was for once unable to negotiate her a contract extension. From this largely positive experience she would in 1890 write her first published article: Across America with Junius Brutus Booth. Having so completed her contracted tour (which she could not have known would be her last in America) and travelled back to the east coast via Panama, a sorely needed opportunity arose to forge paths afresh. Elizabeth accepted an invitation from her friend the widow Sara Bull and left for Europe in September 1888. To begin, she spent a week sightseeing in London, followed by her one and only visit to Norway, to Lysøen Island - the Island of Light. This was the former home of Sara's husband, the Norwegian composer and proponent of the Romantic movement, Ole Bull. She described the trip there as 'like a dream floating into fairy harbors & seeing shores that fade with day.' and noted that it certainly provided at least a beginning of the needed escape from recent experiences past. Ole's brother Edvard provided a strong welcome, but his 'quiet old wife' in Elizabeth's words, was in fact her first true connection to Ibsen, In her youth, she had worked with him at the Norwegian Theatre at Bergen - founded by Ole Bull. It is not however certain whether any special weight was given to this in their conversations of the time. This experience was both Elizabeth's introduction and her one and only visit to the captivating home country of the playwright she would soon come to be defined by. On her return to London, she had telegraphed home to accept a role in New York with a reliable but autocratic actor manager she would certainly not have got along with. But the combination of her striking looks, personality and theatrical intensity quickly won many admirers and stalwart friends for 'Lise' as she would soon become known to friends. Amongst these was the budding Ibsenite Oscar Wilde, then the toast of London, if not yet quite at the peak of his fame. Despite her rather equivocal initial diary description of him as ‘smoothshaven, rather fat face, rather weak; the frequent smile showed long, crowded teeth, a rather interesting presence in spite of certain objectionable points.', in her words many years later, 'he was then at the height of his powers and fame and I utterly unknown on this side of the Atlantic. I could do nothing for him; he could and did do everything in his power for me.' With encouragement from Wilde and with all too vague promises of a role from theatre manager Herbert Beerborm Tree (to whom Wilde had introduced her), she made the decision to cancel her return steamer and stay in London. Wilde was to remain a friend and enthusiastic attendee of her later productions until his downfall. With her decade of experience, much further effort and initially through the web of social introductions, she managed to find initial steady work before then building a reputation as a leading lady of the London stage through the 1890s. This at a time when actor managers still dominated, many of whom, like Henry Irving - as she discovered to her disappointment - often viewed female parts simply as a visual means of showing dramatic pathos. And what of her literal theatrical voice? Elizabeth in fact made several radio broadcasts for the BBC in the 1920s, but unfortunately, typically for the time, recordings were not made. Tree provides a clue, as Elizabeth noted him as saying to her "How American you are, in spite of your voice!". The elocution lessons she had taken had no doubt reduced signs of any American accent she may once have had. Her having some degree of the trained Transatlantic accent of the late 19th and early 20th century might perhaps be a fair guess. As her situation stabilised somewhat, Elizabeth was drawn to the challenging nature of Henrik Ibsen's plays and their radical challenge to societal expectations and gender roles. But she, initially with actress Marion Lea and later the help of her close supporters such as the theatre critic and early Ibsen promoter William Archer, had first to engage in a delicate and frustrating game of diplomacy over the thorny issues of rights, translations and professional pride. Powerful men such as early Ibsenite Edmund Gosse and up and coming publisher William Heinemann were successfully charmed and placated and the path ahead was free. She was now able to organise, manage and produce entire productions independently. One of her many theatrical and personal admirers was (George) Bernard Shaw - although she rebuffed his amorous advances, the strength of his efforts and her fieriness in resisting them have frequently arisen in recent accounts due to his tongue in cheek later description of her having fended him off in her flat with a gun - but by her own account a prop gun, waved at him theatrically! After her earlier tragic experience with George Parks and as someone who delighted in never revealing her true self to those who seemed determined to want to discover it, Archer, her stalwart sounding board throughout her time in London, was the one man of her many male admirers that she allowed herself to become truly intimate with throughout the 1890s. With the morality of the 'New Woman' being strongly debated among not only avid theatre goers but the wider society of the day, Elizabeth's passion in these roles, drawing strongly upon her own experiences, entranced many. These included the 21 year old Bertrand Russell, who revelling in the rebellious mood of the times, stated that Ibsen's plays 'excited me in a very high degree'. Within a few weeks in the summer of 1893, he had read the plays and gone on to see Robins play Helda Wangel in The Master Builder, Rebecca West in Rosmersholm and the title role in Hedda Gabler. For Russell, Elizabeth's parts were 'embodiments of his own fantasies of being released from the confines and restrictions of his past by a woman unfettered by conformity to tradition.' As the 1890s progressed, Elizabeth found the time to supplement her often unsteady theatrical income by becoming a successful novelist, at first under her old pseudonym of C. E. Raimond (until outed by the papers). Novels such as The Open Question drew strongly upon her own experiences both growing up in America and more recently in England. A criticism friends and she herself often levelled was a lack of focus on any single project at one time - nonetheless, her output on all was impressive. Taking Hedda over the Atlantic, the play was premiered at New York's 5th Avenue Theatre in 1898. However, by 1900 the golden era of popularity and challenge of Ibsen's plays was past and Elizabeth expressed disappointment in his final play When We Dead Awaken. She instead looked for catharsis in the new century, embarking on a dangerous adventure in search of her equally idealistic younger brother Raymond. Twelve years older, she had been something of a surrogate mother to him in earlier years in America while her mother was absent, but they had not seen each other since her original move to London twelve years before. As it turned out, Raymond had ended up on one of the last American frontiers in the town of Nome, Alaska. Later famous for the Iditarod dog sled race, it had sprung up almost overnight as a result of the fevered arrival of masses of men seeking their fortunes as part of the Klondike gold rush. He had stepped somewhat inadvertently into a role of community leadership for the new town, sold to him by an associate of a religious movement who had been somewhat economical with the truth of the situation. Raymond was involved in both ministering to and dealing with the sometimes violent and deadly disputes in the wild town, which had not yet seen much sign of the formal structures of authority. It was of some concern to the sceptic Elizabeth that reports indicated that Raymond was suddenly and seriously considering dedicating his life to religion, given his former intentions to work as a lawyer. Although she found her brother and also saw for what was to be the last time her other brother Saxton, in so doing she contracted Typhoid, a condition which was to hamper her health for the rest of her life. But, as planned, her dramatic experiences offered a rich seam of writing material for her bestseller The Magnetic North in addition to other works and articles. Book sale proceeds would allow her to purchase the Florida estate of Chinsegut in 1904 - this had originally been a dream she and he had had decades before. Raymond would go on to live there with his wife Margaret, and Elizabeth would continue to travel back to America from time to time to visit her brother there. Retiring as an actress at the age of 40 in 1902, she in 1909 found a quiet refuge in Sussex, restoring the house at Backsettown and becoming a Henfield resident as the struggle for women's suffrage was reaching its peak and her own thoughts on feminism were culminating. Although rural Henfield was a quiet retreat for her, Elizabeth by her presence alone nonetheless brought the village to centre stage. A few years previously, she was enticed into the movement and had written the play Votes for Women (subsequently expanded into the book The Convert) which had opened to great success in 1906. Joining the long running National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) run by Milicent Fawcett, she became a frequent spokesperson in The Times and other papers and magazines for the Suffragist cause and subsequently the newly evolving more militant Suffragettes (initially a press term of derision) led by the Pankhursts' Womens' Social and Political Union (WSPU). As well as friends from her society life, leaders of the movement visited Henfield over the next few years - on the 29th May 1909, Christabel Pankhurst, Frederick and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence (editors of the WSPU newspaper Votes for Women) and Mabel Tuke (WSPU Secretary) are all shown in the guest book meeting on the same day as the writer H.G. Wells. Although Wells professed to support female suffrage, the meeting that day may not have been entirely convivial. In her biography, Octavia Wilberforce, who lived at Backsettown at the time, detailed that '...he had invited himself, that he had stayed up till past midnight arguing with Elizabeth Robins, who disapproved of his affair with the daughter of one of her friends.' Elizabeth later described Wells' views on women as 'sex-obsessed' and 'antediluvian'! Although still supporting the cause, she left the committee of the Pankhursts' Women's Social and Political Union in 1912 as she felt the continuing militancy was now hindering more than helping. As the frequent advocate in print for the movement (and more rarely in voice, as she disliked public speaking), this had put her in the difficult position of having to criticise her more moderate friends, both in the movement and without. The final straw came when her close friends the Pethick Lawrences were asked by Emmeline and Christabel to leave the committee - Emmeline was of the view that Elizabeth's view on the matter was not of weight as she'd not regularly attended committee meetings! The house was nonetheless set up after the Cat & Mouse Act of 1913 as a refuge for suffragettes recovering from hunger strike and was rumoured to also offer refuge to those wanted by the law! Elizabeth gamely filled in her 1911 Census return for the address with: 'The occupier of this house will be ready to give the desired information, the moment the government recognizes women as responsible citizens.' In 1909 Elizabeth met the young Octavia Wilberforce, Great-Granddaughter of William. Elizabeth supported her goal of becoming one of the second generation of female doctors, for which Octavia's father was to disinherit her. The two became lifelong friends, with Octavia coming to live in Henfield with Elizabeth. The First World War was to provide her with much experience of treating casualties and she achieved her goal in 1920. With the driving support of the new Doctor Wilberforce, Backsettown was to be formally set up as a women's shelter in 1927, remaining so for many decades afterwards. It was insisted upon that there be no mention of illness and frequent provision of fresh produce, some grown in the Backsettown gardens and others no doubt sourced from Henfield's many commercial market gardens of the time. Both women funded and supported women's health services locally including the Lady Chichester Hospital and the New Sussex Hospital for Women. Robins became a familiar (if perhaps remote to most) figure in Henfield and was involved with the formation of the Henfield Women's Institute, where she initially served on the committee of what was then a particularly political branch of a much more political organisation than the WI of today. Virginia and Leonard Woolf were to become friends and visitors of the two women during the inter-war period. Never short of stylish elan, an essential during her acting days and later a useful counter to attacks on 'dowdy' suffragettes, the daughter of the owner of the local bicycle shop nonetheless fondly remembered her frequent visits where she would knit clothes for her dolls. During the inter war years, with Backsettown a busy convalescent home, she was largely based in Brighton at Octavia's surgery. Despite declining health, she continued to write articles for magazines such as Time and Tide as well as working on books, both retrospectives and novels. To her distress, shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, the then almost 80 year old Elizabeth - being an American citizen - was compelled to return to an America she no longer felt at home in by a mixture of onerous wartime 'alien' reporting requirements, the thought that she could advocate more effectively for Britain stateside and ultimately firm advice from the US Embassy. However, she afterwards returned as soon as possible. She had spent the war years working on a comprehensive autobiographical work - tragically her trunks were rifled on the Liverpool docks on her return and the manuscript was never recovered, her legacy suffering as a result. Elizabeth spent her final years in Brighton at 24 Montpelier Crescent, looked after by her long time friend Octavia and regaling visitors with stories of her life and the Victorian stage. ~ Postscript ~ In 1960, a plaque in her memory was unveiled at Backsettown by amongst others, her latter life friends Leonard Woolf and Sybil Thorndike. Famous in her time, her legacy has been partly obscured perhaps by her early theatrical retirement, her long life, and a thirty year hold she put on the opening of her extensive archives in New York. However, the last three decades have seen an increased appreciation, with two biographies leading the way and a spotlight shone upon Votes for Women! during the centenary of the Representation of the People Act in 2018. With the Backsettown convalescent home at Henfield finally sold in 1991, the managing Trust subsequently passed the rights to the Robins papers to the charity Independent Age - a cause Elizabeth would doubtless have supported in struggles to stay productive in the face of health issues in her later years. In 1919, she had written in her diary - 'To be a successful old woman - that's the great achievement.' It is hoped her story will now be better known in her beloved Sussex too. In 2019, as part of the Horsham District Year of Culture, two new community mosaics were unveiled in Cooper's Way, Henfield, highlighting the village's role in women's suffrage. One shows a violet, both symbol of the suffragettes and a tribute to the Misses Allen-Brown, female owners of their own famous violet nursery and suffrage supporters and friends of Robins. The other shows Backsettown, with the waving figure of Elizabeth as suffragette standing in front. By R. S. Gordon, 2020 Research into Elizabeth always reveals many fascinating sketches of her life and times - it is hoped to release further articles focused on specific aspects in the future. For a further selection of restored and colourised photos of Elizabeth, see her page in our 'Henfieldians Past' section.  The 2019 mosaic of Elizabeth and Backsettown, a community created project led by Creative Waves and the Henfield Community Partnership. Photo: RSG References

Gates, Joanne E., Elizabeth Robins, 1862-1952 Actress, Novelist, Feminist (The University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, 1994) Hill, Leslie Anne, Theatres and Friendships: the Spheres and Strategies of Elizabeth Robins (University of Exeter Thesis, 2014) John, Angela V., Elizabeth Robins, Staging a Life. 2nd ed. (Tempus Publishing Limited, Stroud, 2007) Moessner, Victoria Joan, Gates, Joanne E., eds., The Alaska Klondike Diary of Elizabeth Robins 1900, (Fairbanks, University of Alaska Press, 1999) Monk, Ray, Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude, 1872-1921, Volume 1 (London, Vintage, 1996) Powell, Kerry, Women and Victorian Theatre (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997) Robins, Elizabeth, Both Sides of the Curtain (London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1940) Henfield Museum Collection/Archives In a time when as a species we seem to be too often struggling to rediscover our connection with nature, we are able to shine a light on a notable green heritage in Henfield. To help inspire Sustainable Henfield 2030, take a look back at a life from Victorian Henfield... Charles Green was born in Lewes around 1826, but by the time of the 1841 Census, he had arrived in Henfield and was lodging at Church Street in the house of Sara Ward as a 15-year-old Apprentice Gardener. Each day, he would walk out of Church Street and proceed up the High Street towards Golden Square and work, where, for almost a century and a half, a great verdant mass of flora greeted visitors to Henfield - also unmistakable for those arriving across the Common or up Barrow Hill. This was the famed garden of the Italianate Barrow Hill House, home to William Borrer Esq., one of the foremost botanists of the first half of the 19th century, a particular expert on Salix and lichens (and recently featured in the museum's roving display case). Green had had the high good fortune to be taken on by Borrer. He no doubt collaborated closely over the next two decades, continuing to put the main physical manifestation of Borrer's life's work into the soil. By 1851, he was lodging at Chatfields with Daniel Buckwell and Daniel's wife Mary and daughter Harriett. Daniel too was a gardener and most likely also employed at Barrow Hill. In November 1856, Charles married Lucy Rowland, but their wedded life lasted only a little over a year. She was sadly to die aged just 29 in December 1857. Her grave today lies beside a yew tree in Henfield churchyard. Two small stones also lie at the foot - unreadable and although suggestive of children's graves at first glance, most likely footstones, moved later when the yews were planted for Victoria's Golden Jubilee. However, the timings suggest that the birth of her daughter was the likely cause of Mary’s death. By the time Borrer died in 1862 at the age of 80 - tragically from a cold caught attending the Christmas play of the school to which he had been a primary benefactor - Green had progressed from Apprentice Gardener to the Head Gardener of a nationally renowned botanical garden with over 6600 separate species of plants. He would likely have assisted with the subsequent transfer of many of the rarer plants to Kew Gardens (along with Borrer's Herbarium - his lifetime collection of books of dried specimens). By this point, he was living at Mount Pleasant, Weaver’s Lane on Henfield’s ridge, looking out towards the South Downs. A widowed father looking after his four-year-old daughter Lucy with help from his mother-in-law (also Lucy!). Green's photo was apparently taken at the garden of his next employer, William Wilson Saunders, who like Borrer was a fellow of the Linnean and Royal Societies and no doubt got the inside track on acquiring Green's talents after Borrer's death. In late 1863, Charles had also remarried to Emily - the sister of his lost wife Lucy. Green subsequently elevated Saunders' garden at Hillfield, Reigate to national horticultural fame. It apparently contained over 20,000 species and was 'one of the most extensive botanical collections then seen in a private garden'. Eleven years later Saunders suffered financial catastrophe and the collection was sadly dissolved in 'one of the greatest calamities that has befallen horticulture in our time.' Having to move on, Green ran a commercial nursery at Reigate for a few years where he continued to popularise plants and pioneer new hybrids. For example, at the January 1876 meeting of the Royal Horticultural Society, the Floral Committee voted him a botanical commendation for his submission of the other-worldly looking lithops succulent Mesembryanthemum truncalatellum, with thanks also given for his other submissions, including the orchids Masdevallia melanopus and polysticta (plus variants thereof). Before too many years had passed, Green was happily recommended to Sir George Macleay by Saunders, allowing him to move out of the commercial nursery business and back to his much-preferred world of private gardens. His final garden at Macleay's Pendell Court was described as containing 'one of the richest private collections of plants in Europe'. Both it and Hillfield were famed for their large greenhouses, particularly focused on orchids and ferns. Descriptions of both gardens still survive. Green died at Reigate at the age of 60 in 1886. Poignantly, it seems he wasn’t brought back to Henfield for burial beside his wife and children, and one side of the shared gravestone remains blank, awaiting an inscription never to come. Perhaps those dealing with the funeral simply weren’t aware of his family from thirty years prior in Henfield (*Update - see James Driver's comment below of 29th March 2023 for the remarkable likely reasons behind this). The anonymous author of his obituary in The Garden magazine stated that 'Few men of the present day possessed such an extensive knowledge of plants...and his love for all kinds of plants, especially those out of the ordinary run, was only rivalled by his skill in growing them.' Green was 'Unassuming in his manner, ever ready to impart information about plants, he won respect from everyone. His death is a real loss to horticulture, for it may truly be said that he was the means of preserving many a plant that would have been cast aside in accordance with the vagaries of fashion, and of rescuing other fine plants from the oblivion into which they had fallen.' The obituary also notes that 'Borrer's Garden contained one of the finest collections of plants, particularly of hardy perennials, then existent'. A touching anecdote was sent by letter to The Garden magazine in response to their previous publication of his obituary: 'Of all the plant growers that I have ever known, Green seemed to me to individualise and love his flowers with an affection I have never seen equalled. As a proof of this I may mention that he gave to me as the reason of relinquishing his nursery at Reigate...that he could not bear to part with the plants he had been tending for years. I remember his saying that to me in a quite broken-hearted sort of way, and as a nurseryman's business consists in passing things rapidly through his hands, Green soon had enough of it, and he was much more happy at Pendell Court. How successfully he managed that most splendid collection not a few can remember, but I have put together these few remarks to emphasise the fact that he loved his flowers as much as most men love their own children. H.E.' Green is still discussed today, cropping up in a journal article in May this year (with some recent research having discovered his photo and a little of his elusive story). Botanists at the University of Johannesburg discussed his likely commemoration in 1880 by the rockery plant Aloe greenii. Due to confusion with the name having already been used five years prior, they supported the renaming of this plant to Aloe viridiana, which still credits Green, if now a little more loosely. He is credited as having been the source of the name for several others, with more likely but not definitely attributed: * Sempervivum greenii ('houseleek', a succulent perennial) * Mormodes greenii (an orchid, flowered by Green's employer Wilson Saunders and named in Green's honour by J.D. Hooker in 1869) * Zygostates greeniana (an orchid, now renamed Centroglossa greeniana) * Streptocarpus ×Greenii (a Cape Primrose hybrid raised by Green ~1876 from S. saundersii - also named for Wilson Saunders - and S. rexii) - Possible - * Haworthia greenii (a succulent) * Echeveria greenii (a succulent) His story having been lost in shadow for all too long, Charles Green surely now deserves due credit for his two decades of work at Barrow Hill, the foundation of a career for a man whom the then Director of Kew Gardens, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, in 1869 called 'one of the most accomplished and skilful of English gardeners'. Article by Robert S. Gordon, first published in the Henfield Parish Magazine 2019. Updated with thanks to Alan Barwick and James Driver for additional information, April 2023. Images of some of Green's plants References

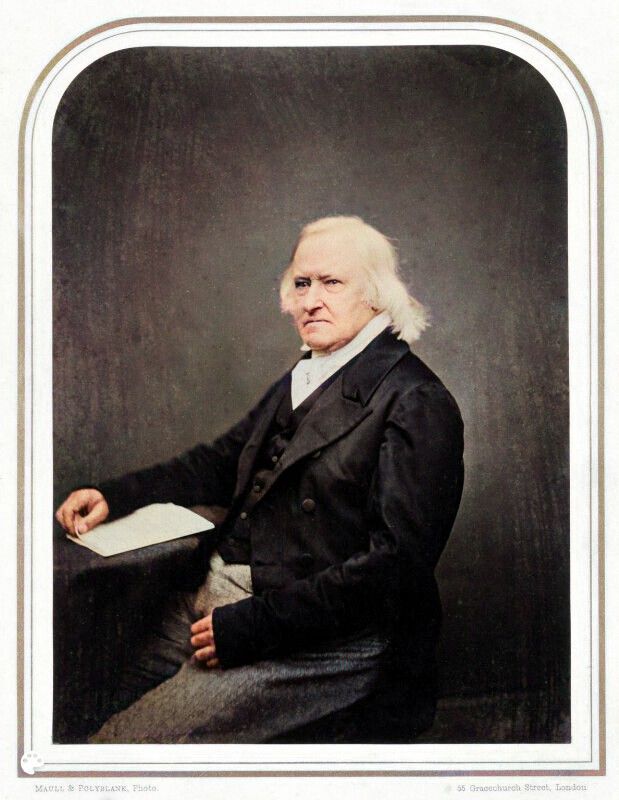

Anon, The Gardeners' Chronicle: a weekly illustrated journal of horticulture and allied subjects, Volume V, London, 1876, p. 118. Anon, The Garden: an illustrated weekly journal of gardening in all its branches, Volume 30, London, 1886, p. 530 Gideon F. Smith, Estrela Figueiredo, Joachime Thiede, The elusive Mr Green and the eponymy of Aloe greenii Green ex Rob. and A. viridiana. Bradleya 37, 2019, pp. 41-45. Driver, James, Charles Green (1826-86): Head Gardener to Sir George Macleay at Pendell Court, Surrey. Garden History, vol. 40, no. 2, 2012, pp. 199–213. The photograph above is the only known of one of Henfield's most renowned figures, botanist William Borrer III (1781 - 1862). His stern expression belies what was said to have been a kind and gentle nature, although one astute in the management of his domestic affairs as local squire as in his study of plants. William's father was a wealthy farmer and grain merchant from a family associated with the Brighton Union Bank, who supplied local army camps during the Napoleonic Wars. While a young man, Borrer assisted with these duties, taking every opportunity these travels around Sussex afforded to collect, record and begin to build his impressive expertise and passion for the natural world. Coming into the family wealth, he was able to dedicate himself in a high degree to his passion for flora and the natural world. George Busk, like Borrer, a Fellow of the Royal and the Linnaean Societies, described Borrer's early inspiration: 'To this study he had, in fact, a bent from his earliest years, and his brother, John Borrer, Esq., of Portslade, who was about two years his junior, has stated that he did not remember the time when he was not enthusiastic in his love for flowers, and in his admiration of the vegetable world in general; so that there was no muddy ditch, no old wall, no stock of a tree, no rock or dell, no pool of water, or bay of the sea, that did not add to his delight, and open to him a wide field for investigation or enjoyment.' Based at Barrow Hill in Henfield, his own noted garden held 6600 species on his death, as recorded by his head gardener Charles Green prior to the rarer plants' removal to Kew Gardens. The Gardener's Magazine stated in their description of 1838 that 'the number of species of rare herbaceous plants is so great, that we do not know any garden in the neighbourhood of London that can be compared with it.' Borrer travelled widely around Britain to collect samples and corroborate or disprove findings. One representative tale was reported in his obituary in the Journal of the Linnean Society: 'A Westmoreland "guide", in the Lake District, had represented the discovery...of a habitat for Cypripedium Calceolus; but Mr. Borrer, doubting the correctness of the statement, was at pains to visit the spot for three years successively, at the time of flowering of the plant, and was at length able to expose the attempted imposition.' Corresponding with and providing an expert sounding board for both enthusiastic amateurs and the leading professional botanists and naturalists of his day, he was a leading figure in botany in this country, much credited by luminaries such as Charles Cardale Babington and both William and Joseph Hooker. His West Sussex Gazette obituary stated that 'there was not a work on British botany for the last 50 years that has not acknowledged his assistance', which literal or not, gives an idea of his activity. George Busk of the Linnean Society stated that 'Mr. Borrer's extensive and valuable collections of plants, as well as the ample stores of his exact knowledge, were always at the service of his friends and fellow-labourers.' Sussex historian Mark Lower stated of Borrer, that 'I might from my own knowledge mention some to whom, when pecuniary means were wanting, this benevolent man and true friend of science made valuable presents of scientific apparatus'. While Borrer was debatably Britain's foremost botanist for a period in the early 19th century, this was certainly the case for lichens and certain other specific genera such as willows (salix), roses and succulents. Regarding salix - or willow - on August the 12th, Borrer's friend and fellow botanist Charles Cardale Babington sent an illuminating reply to a younger correspondent who had apparently been defensive about referring to Borrer and another's opinion on willows: 'I am rather amused at your defending yourself for mentioning to me the opinions formed by Messrs. Borrer and Watson concerning the Willow. The opinion of the former upon any plants and more especially the Willows, has very great weight with me. I always feel doubtful of an opinion when I find that he has arrived at a different one concerning any species.' Borrer married Elizabeth Hall, the daughter of one of the partners at the Brighton Union Bank, and they had 13 children - 3 sons and 5 daughters survived to adulthood. Their elegant new home of Barrow Hill house was built upon their marriage in 1810. In William's case, although he was appointed J.P. and active in village life as required of man of his position, he was of a personally modest and fairly retiring nature. The family were nonetheless well known benefactors to Henfield. Projects included those in support of the church and local schools, with funding for an extension to St. Peter's Church for the use of local children (removed during the drastic remodelling of the church later in the century) and a donation of £2000 made to the Vicar's stipend - so encouraging the resumption of full time services. Indeed, the new Vicar Charles Dunlop was to marry Borrer's daughter Fanny - they moved into the newly built Red Oaks, the land and house having been given by Borrer and named after the American Red Oaks he had planted there. When it came to education, as well as providing funding, he constructed local schools on his own land (including the Infant School at Nep Town), and furthermore personally taught several boys at Barrow Hill, subsequently finding them appropriate employment. Perhaps it was symbolic that Borrer was to die from a cold caught while attending the annual prize giving at Christmas 1861, at 'the National School which was established principally by his exertions'. Such was the level of respect to 'William Borrer, Friend of Henfield', that all shops closed on the day of his funeral, with over 300 attendees, many from out of town. Borrer's probate came to just under £70,000, over £8 million today. Perhaps the most striking commendation of Borrer's unrivalled breadth of knowledge comes from the famous Hooker botanical family. Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, twenty year director of Kew Gardens, described Borrer as 'long the Nestor of British botanists'. (Nestor, the wise king of Pylos in Homer's Odyssey). As a stark illustration, his father, Borrer's good friend and earlier twenty four year Kew Director, Sir William Jackson Hooker, received from Borrer for the year of 1823 alone 145 letters on botany. In 1855 Sir William dedicated the 7th edition of his and George Walker Arnott's seminal work, The British Flora, to Borrer with the following words: 'No one, we formerly remarked, has a critical knowledge of British plants superior, and scarcely any equal, to your own; and we desire thus again to testify how much, on many occasions, we have profited by the numerous notes and observations you have kindly communicated to us. That the uninterrupted friendship which has subsisted for so many years between us, may continue during the remainder of our lives, is the sincere wish of, Dear Sir, Your faithful and affectionate Fellow-labourers, The Authors.' Article by R. S. Gordon, 2020 Photo Gallery References

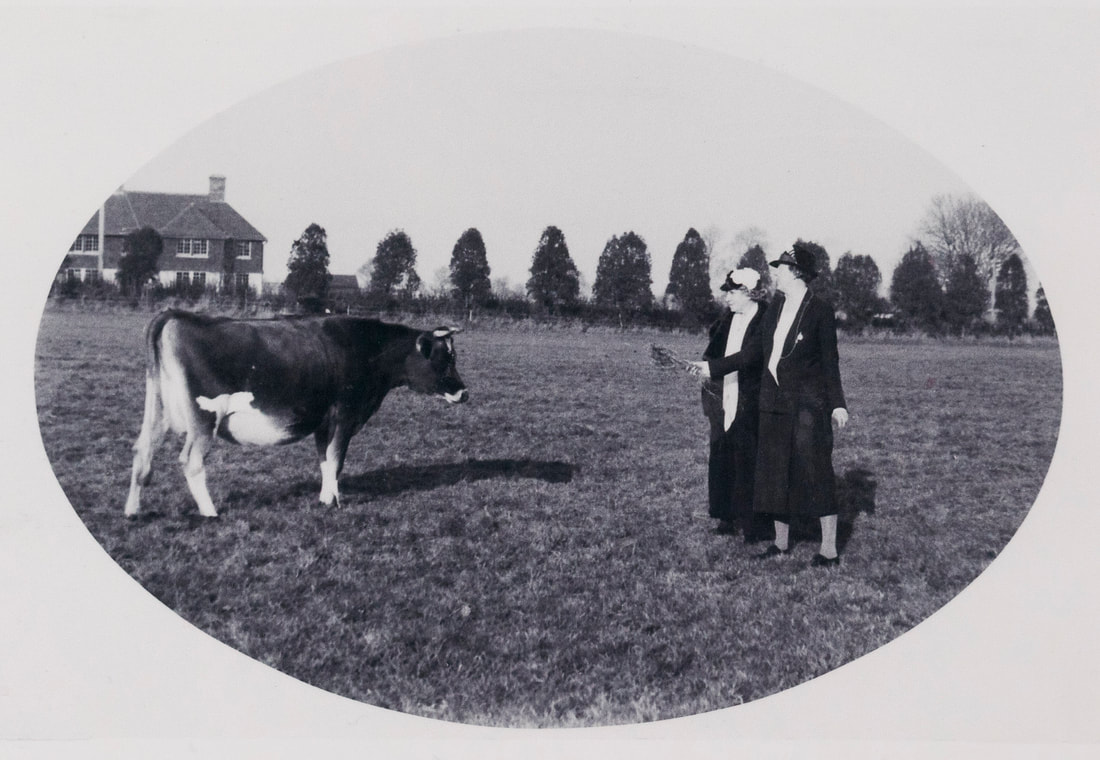

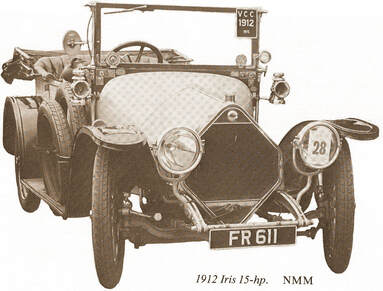

George Busk, The Journal of the Linnean Society: Zoology, Volume 6, London, Linnean Society, 1862, pp. lxxxix, lxxxviii. Loudon J.C. (ed), The Gardener's Magazine and Register of Rural and Domestic Improvement etc., Volume IV , London, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1838, pp. 501-503 Anon, The Journal of the Linnean Society: Zoology, Volume 6, London, Linnean Society, 1862, pp. lxxxix-xc. Sir William Jackson Hooker, George A. Walker Arnott, The British Flora etc., London, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1855. Mark Antony Lower, The Worthies of Sussex: Biographical Sketches of the Most Eminent Natives etc., by subscription, 1865. Joseph Dalton Hooker, A Sketch of the Life and Labours of Sir William Jackson Hooker etc., Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1903, p. lxxxi. H.C.P. Smail, Watsonia, Volume 10, 1974, pp. 55-60.  Miss Margaret Knowles. Image from the Marjorie Baker Collection, Henfield Museum (CC BY-NC-SA) A person who deserves greater recognition for her work in Henfield is Miss Margaret Knowles of Henfield Place. She gave a large tract of land, part of the garden of her house, to the village to be used as a recreational area for the children of the village. The gift was to commemorate the Silver Jubilee of King George V in 1935, and was therefore known as the King’s Field (next to the sports centre). An oak tree was planted in memory of the gift, but was unfortunately felled during the building of Northcroft. The land originally bounded Upper Station Rd, but in the 1960s houses were built along the road and additional land was acquired at the side to compensate. There is now no recognition of her gift to the village. Miss Knowles was born in London to a Charles Julius Kino on 22nd May 1877. Family tradition gives his birthplace as Russia, coming to England during the 1870s. He married Louisa Essinger in London in 1874. The 1881 census shows them living in Edinburgh Terrace, London. Margaret had 4 siblings, Hugh C, and Guy J. F. and Kate C. and Mabel. Guy was a civil engineer who started a motor vehicle company with Lucien Legros, the son of the artist Alphonse Legros. They produced the ‘Iris’ car, which in early days at least was described as ‘cumbersome and slow’ with a slow revving engine and was nicknamed the ‘Old Buggerinas’. Charles Kino is recorded as a tailor and woollen Warehouseman. By 1891 the family name changes to Knowles. It would seem that Charles also indulged in property development in London and built 7 blocks of apartments on Prince of Wales Drive, possibly with Lord Battersea. He began collecting artwork and became friendly with 2 artists: Whistler and Rodin, Guy as a child would play with clay in Rodin’s studio. After Charles died, his wife Louisa developed an infatuation with Rodin and commissioned a cast of Rodin’s “Brother and Sister” for her son Guy in March 1903. When Charles Knowles died he left his son Hugh £1.2M and his son Guy £400,000. It is interesting to note that before his death he brought Linkenholt Manor in Hampshire, including the whole village. Margaret was left several endowments and large sums of money. It is believed that Margaret came to Henfield Place in 1913. In 1939 at the start of the war, she allowed Henfield Place to become the ‘Henfield Central Hospital Supply Depot’. From 1939 – 1945, 8448 garments were sewn in various workshops and sent to Henfield Place to be packed and sent to P.O.Ws, Emergency Maternity Hospitals, people blitzed and liberated captives. Also, due to the dedicated home knitters, 3272 knitted garments were sent to British and Allied Forces; the final total of work reached 13,022, all being packed and sent from Henfield. All local men were given Christmas parcels. Proudly no man was forgotten. Henfield Central Supply Depot provided garments and bandages to Shermanbury Grange Hospital and the Royal Sussex County Hospital. Margaret Knowles was the driving force behind an organisation called the Girls Friendly Society (GFS) in Henfield. The GFS was a national girls organisation founded in 1875. It was originally set up to help young girls/women who left home in the country to work in towns and cities, and who very often had no friends or family and were extremely vulnerable. The Society’s aim was to befriend and mentor these girls. In 1880, the Society had 40,000 members and provided lodges which offered cheap good quality accommodation for young women working in domestic service or mill and factory workers. During the war years the Henfield GFS threw itself into the war effort raising money for, amongst others, the White Horse Club for boys and girls in London; another was to provide housecraft training for 16 - 18 year old girls. The GFS carried on after the war and was active into the 1960’s and became a youth club for young girls. All in all, Miss Margaret Knowles gave a lot to the village both in time and money; next time you walk through the Kings Field to the Leisure Centre or go and play tennis or football, have a thought for this kind person. Margaret’s sister Kate Christine Knowles set up the ‘Forget me not’ League, originally set up to send books and games to captured allied servicemen, but it developed into giving parcels of toiletries, shaving equipment and small luxuries. To join the League you paid a fee of 1s (5p) and then undertook to raise money by organising dances, whist drives, etc. When you raised 20s (£1) you were awarded the Forget-me-not medal. Margaret died on 25th January 1947, leaving around £300,000 (equivalent to almost £12 million in 2019). It is interesting to note that the village that Kate lived in named a road after her – Knowles Walk; and Henfield named a road after Margaret – Knowles Close. It is not known why Charles Kino changed his name and why he chose Knowles, but it is known that Henfield is better off for having had such a kindly benefactor and friend. By Steve Robotham (Assistant Curator) with thanks to Maureen Fletcher and Adrian Vieler (researchers), first published in the Henfield Parish Magazine, June 2019. Iris car image added 2020. Selected References - Henfield Museum records (2015/34/P1) - Census forms - The will of Margaret Knowles  Miss Margaret Knowles. Image from the Marjorie Baker Collection, Henfield Museum (CC BY-NC-SA)